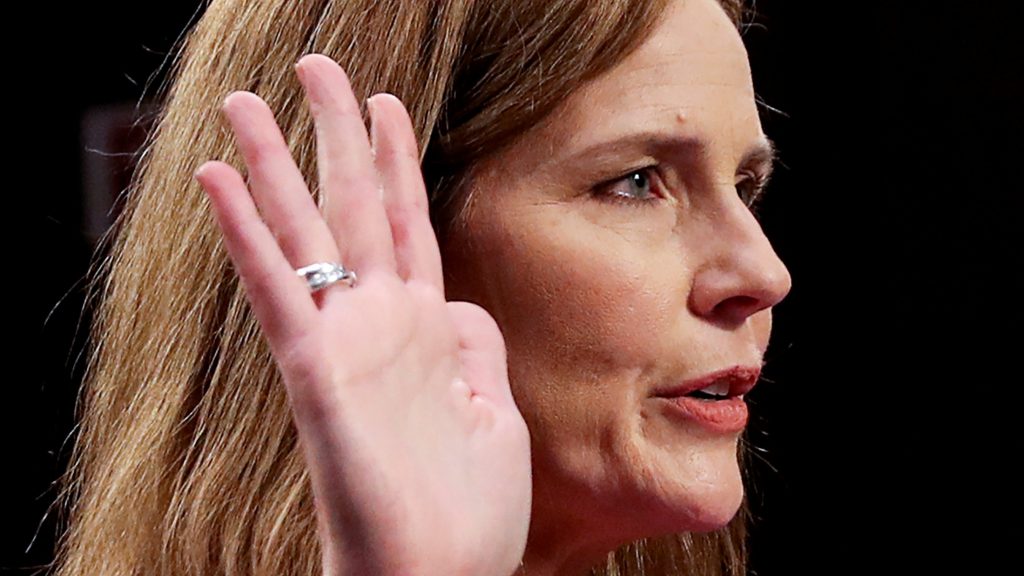

Amy Coney Barrett is expected to be confirmed to the Supreme Court on Monday evening, after the Senate held a rare Sunday session during which a majority of senators moved to advance her nomination to a full vote.

In a 51-48 vote on Sunday, senators moved to invoke cloture on Barrett’s confirmation—setting a time limit on the debate over her confirmation, with a final vote at the end to confirm her to the Supreme Court. She was nominated by President Trump to replace the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Court, on Sept. 26.

Barrett, a Catholic, currently serves as a judge on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, and is a former professor at the University of Notre Dame School of Law. If confirmed to the Supreme Court, she would be the sixth Catholic on the bench, with a seventh, Neil Gorsuch having been baptized Catholic but now practicing as an Episcopalian.

Sunday’s cloture vote fell largely along party lines, with two Republicans—Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska)—voting with Democrats against bringing up the final vote on Barrett. Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Angus King (I-Maine) also voted “No.”

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), the Democratic vice-presidential nominee, did not vote on Sunday as she was campaigning in Michigan ahead of election day on Nov. 3. She told reporters on Saturday that she would vote against Barrett in the final confirmation vote.

Senators spoke from the Senate floor on Barrett’s confirmation throughout Sunday afternoon and evening, and into Monday morning.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) said that Barrett “represents a threat to women’s reproductive rights” and warned that if confirmed, “she would likely be the court’s most extreme member on reproductive rights.”

When the Senate Judiciary Committee was considering Barrett’s appointment to the Seventh Circuit in 2017, Feinstein opined that Barrett’s Catholic faith could improperly influence her judicial opinions on matters like abortion. Feinstein told Barrett “when you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you, and that’s a concern.”

Last week, Barrett’s nomination advanced out of the Senate Judiciary Committee with a unanimous favorable recommendation, after 10 committee Democrats boycotted the vote.

From Oct. 12-15, the committee held four days of hearings featuring statements from senators and from Barrett herself, questioning of Barrett, and witness testimonies for or against Barrett’s confirmation.

Senators grilled Barrett on a number of issues including health care, voting rights, and abortion and contraception.

Barrett repeatedly refused to opine on previous Supreme Court rulings, saying that she did not want to influence any possible case she might have to consider as a justice; she explained that she wanted to offer “no hints, no previews, no forecasts.”

Senators asked Barrett multiple times about Griswold v. Connecticut, the Court’s 1965 ruling that legalized contraception; while Barrett refused to opine on the ruling, she emphasized that “Griswold is very, very, very, very, very, very unlikely to go anywhere.”

Regarding the Court’s legalization of abortion in the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, Barrett would not say that it is “super precedent,” or a legal theory that certain Supreme Court rulings have been upheld so many times and are seen as institutional and cannot be challenged.

Some senators warned on Sunday that Barrett could undo legal contraception on the Court.

“I can’t even imagine going back to Griswold v. Connecticut—a time when we had to fight just to have contraception,” said Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.).

Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.) said that Barrett could rule on contraception cases such as those of the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate, which businesses and religious non-profits including the Little Sisters of the Poor challenged in court.

He also said she could rule with other “conservative” justices “as a bulwark against further expanding privacy protections in family life.” As an example, he noted the case Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, for which oral arguments are scheduled at the Court in November.

That case involves the Catholic Social Services of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which had contracted with the city on foster care placements but saw its contract stopped in 2018 when the city demanded that it work with same-sex couples.