The coronavirus pandemic has caused Catholic schools across the United States to close. With no clear timeline for when they might reopen, parents, students, teachers and schools are finding innovative ways to balance distance learning and home life.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization last week, after spreading to more than 100 countries worldwide. In the U.S., there were more than 5,200 confirmed cases of the virus as of Tuesday afternoon.

Dioceses have halted public Masses indefinitely, and states are beginning to shut down public events, impose curfews, and order the closure of restaurants and bars. Many Catholic universities and schools have already closed their campuses and have begun to transition to distance learning.

While colleges and universities have offered online courses for years, most Catholic elementary and high schools are trying to adapt quickly to accommodate distance, with teachers, parents, and students facing unforeseen challenges.

Tim Hruszkewycz, a high school English teacher at Villa Madonna Academy in Northern Kentucky, told CNA that he received notice late last Thursday that the school would be transitioning to remote courses, because of the pandemic.

Despite preconceptions that working from home might be easier, “it’s not easy,” he said. “It’s way more work, it’s way more stressful.”

Hruszkewycz, however, said he had anticipated the eventual closure of the school campus for weeks and had already mentally prepared the students for distance learning.

He teaches five classes of students in grades 10 through 12, and planned virtual lessons and courses for each class. “On Thursday, I basically made a million packets” for the students, he said, before they went home.

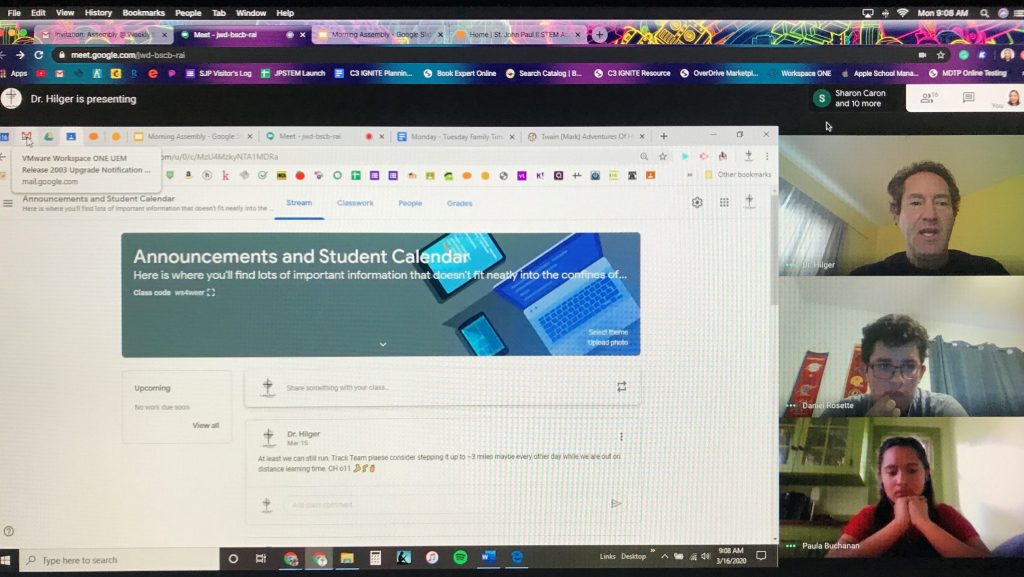

While initially told that the campus would be closed for two weeks, Hruszkewycz has been preparing for a month-long exercise in remote teaching. He conducts classes through video conferencing on Google Hangout, which has video chat and text chat functions for students to interact with him.

He still wears a shirt and tie to mimic a normal classroom environment as closely as possible, and has assigned novels for students to read, so they will have plenty of material to discuss when they return to in-person classes.

“I have really motivated kids,” he said, “but even the most successful kid” will have challenges to study hard at home.

“It’s really tempting to find ways to blow off this time,” Hruszkewycz said. “It’s just one giant impediment between student success and just the ease of moving on with life.”

In the Archdiocese of Washington, which has 18 high schools and 54 elementary schools, Wendy Anderson, associate superintendent of academics and leadership in the archdiocese, told CNA that a significant challenge to distance learning has been lack of internet access for some of the younger children.

“It’s a lot easier for high school kids to kind of get online and keep up, but for younger children we have to have some pretty creative solutions,” Anderson said.

Most important, she said, teachers are acting as “ministers” by praying with the students, even in this extraordinary time.

“I think it’s important that they’re incorporating Catholic identity through this, that teachers are doing prayer with kids, keeping the faith up, giving the families alternatives, prayer services as alternatives to Mass,” she said. “We’re not going to lose sight of our mission through this.”

High schools were “pretty quick” to transition to digital learning, Anderson said, but with the elementary schools “we don’t assume that all children will have access to the internet.”

A “majority” of the archdiocesan schools are utilizing digital learning, she said, with platforms such as Google Classroom.

“The schools are closed, and we’re not trying to say we’re open completely for academics, but all of our schools are offering things to keep kids busy and up-to-date on their studies as much as possible,” she said.

In the case of Don Bosco Cristo Rey high school in Takoma Park, Maryland, students are also enrolled in work-study programs, so they are learning to work remotely as well.

In the Diocese of Brooklyn, there was “anxiety” about having to make mass changes in the pandemic, district superintendent Michael LaForgia told CNA.

However, he said the feedback so far has been “extremely positive” as “faculty and principals have gotten together” and “rolled up their sleeves.”

“We have a very diverse diocese,” LaForgia said, with both affluent and poor sections, and the diocese wanted to ensure schools would receive an equitable distribution of resources and attention.

One school in Queens has a large immigrant population with English as a second language, he said, so the school principal hosted families last week for an interactive presentation about using the app Zoom so their children could learn electronically.

The diocesean communications and technology arm, DeSales Media, had already begun partnering with schools to provide them devices for remote learning before the coronavirus became an issue, LaForgia said.

Some parents do worry that an extended break from in-person classroom settings could mean that their child falls behind in grades or certifications. It is a concern, LaForgia said, but one shared by parents of students at both public and Catholic schools, and one which will be confronted as a community “as the days turn into weeks.”

“What we’re finding is, everybody is collaborating, and everybody is working for the same goal,” he said.

Meanwhile, many parents now working from home face the additional challenge of ensuring their children are still learning.

Two homeschooling mothers—Elizabeth Foss, a Catholic mother of nine children, and Stephanie Weinert, a mother of four children—who are both bloggers and active on Instagram, co-hosted a virtual discussion on Sunday night for mothers whose children will be transitioning from school to learning at home.

“This is qualitatively different from homeschooling,” Foss said of the current situation.

Many mothers are still working from home, but now have to attend to the educational needs of their children as well. The schoolwork many of the students have been given is not enough to fill eight hours a day, it is closer to three or four hours, she said, leaving a significant gap of time for parents to fill.

The virtual discussion on Sunday emphasized the need of parents to limit children’s unnecessary screen time, reserving it for more scholastic endeavors.

“In order to do that, we have to model that ourselves,” she said, urging parents to practice moderation in use of the internet as an example for their children. “We don’t need the continuous drip of anxiety,” she said of reading constant Coronavirus news updates.

Foss said that the forced drastic shift in home life brought on by the coronavirus could be an opportunity for a much-needed shift in societal priorities: Parents now might have more time to make family dinners and involve the children in household chores and affairs—a chance to “slow down and really acknowledge relationship-building,” she said.

“Maybe the bigger question is why are we so out of touch with the rhythm of family, and can we see this as an opportunity to reestablish that rhythm as a culture?” Foss asked.

“I can’t imagine any other scenario where an entire culture has stopped and said, okay, who are the people who I am going to be confined with, and how is that set of people my family? And what are we to one another, and how do we best help and bring out the best in each other? Whether that’s school or not.”