Ahead of the U.S. bishops' meeting in Orlando, Florida, June 14-16, Bishop Joseph N. Perry said that new investigations by church institutions into their involvement with slavery and Indian boarding schools are "very healthy" and aid a collective examination of conscience.

"It's never too late to delve into one's past. Examination of conscience is something we're used to as Catholics," the bishop told OSV News May 30. "It's never too late to look at one's self and to see what we're not noticing, to come to a better understanding of what we're ignoring or that we're too selfish to recognize. It's never too late to establish regrets. And ... it's never too late to apologize."

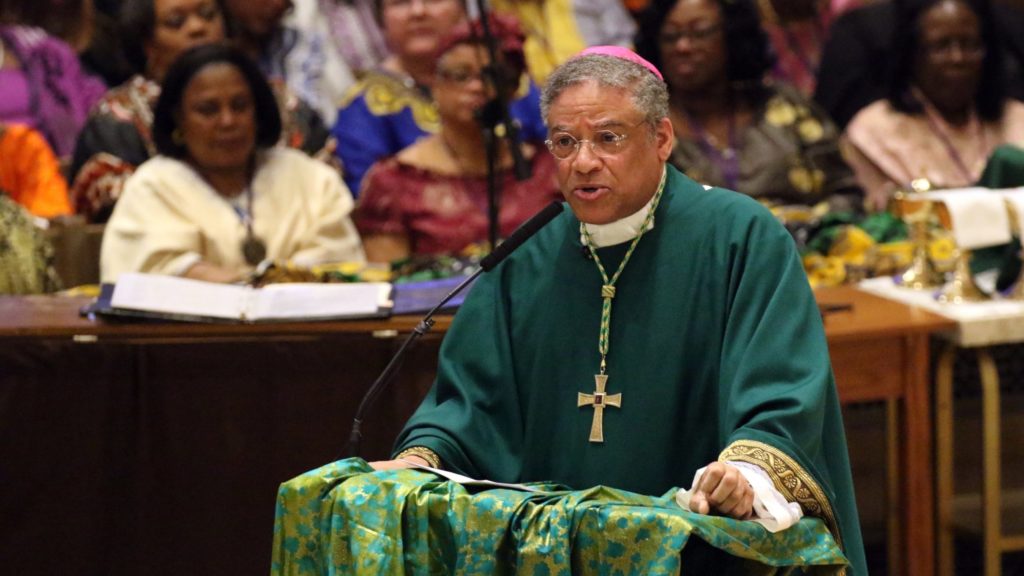

Bishop Perry, 75, was named chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' Ad Hoc Committee Against Racism May 10. An auxiliary bishop of Chicago, he succeeded Archbishop Shelton J. Fabre of Louisville, Kentucky, who served two terms as the committee's chairman.

Bishop Perry commended fact-finding efforts underway, such as Archbishop William E. Lori of Baltimore establishing a commission to research the Archdiocese of Baltimore's ties to slavery, announced May 22; and a group of archivists and historians publishing May 9 a list of 87 Catholic-involved American Indian boarding schools in the United States to help tribal nations access their archival records.

He also noted the Jesuits' ongoing investigation into their order's 19th-century slaveholding practices at Georgetown University, which included selling whole Catholic families -- 272 Black men, women and children they baptized -- to Louisiana plantation owners in order to financially rescue the university, which boasted a $1.5 billion endowment in 2015. The GU272 Memory Project has so far located 8,000 descendants of the families sold to save Georgetown.

Investigation into the church's institutional involvement in racist practices and systems "leads the church to a better understanding of its human-ness, its complicity in evil. It also stirs up sympathy, if not empathy" and leads to contrition, Bishop Perry said.

"It engenders a deeper understanding that we didn't have before. It gets rid of a compromise that we made of the Gospel -- that we haven't lived it as perfectly as we should have, the Lord's teaching of love of neighbor," he said.

Bishop Perry, who is African American, said that he experienced racism as a child growing up in 1950s Chicago, where he watched "white flight" from his neighborhood, school and church. Places that had been racially diverse quickly became majority African American, including his own parish, he said. Racism was perpetuated by redlining -- systemic denial of mortgages and insurance-based loans in predominantly Black or non-white ethnic neighborhoods regardless of a person's credit history or financial status -- and other discriminatory housing practices, he said.

"My thing has always been (that) we're certainly more when we are together, but when we're separate, we're less -- and to get people to appreciate that is a tough nut to sell, because it digs right into people's sense of opportunity and wealth, sense of privilege, and all those kinds of things," he said. "Those are the kinds of issues that people would get from their pews and leave as the homily was being preached."

While society fights racism through the courts and public policy, the bishops' work has emphasized racism as a sin and the need for personal conversion, he said. "We have the Gospel," he said, "and I think that's one of the most principal tools of this whole ad hoc committee, and that is proclaiming the Gospel and the church's treasured social teaching."

While much attention is focused on racism against African Americans and Latinos, racism is not exclusively a "white problem," he said.

"People question all the time whether African Americans and Latinos can be racist. Oh yes, we can. We can have skewed judgments about people, and these kinds of ... human behavior and activity keeps people at a difference, so we never come to know each other. We never come to realize that we all have red blood," he said. "We all suffer. We all cry. We all experience the same things. The differences amongst us or between us are very, very few."

The Ad Hoc Committee Against Racism was established in 2017 under Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, who was then serving as USCCB president. It was initially led by Bishop George V. Murry of Youngstown, Ohio, with Archbishop Fabre being appointed to the role in 2018, while he was bishop of Houma-Thibodaux, Louisiana. He was named archbishop of Louisville in March 2022 and requested that a new committee chairman be named.

In 2018, the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the committee issued "Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love, A Pastoral Letter Against Racism." It also has produced "Everyone Belongs," a children's book inspired by the pastoral letter. The committee has been assisting Catholic institutions and dioceses address questions around racism, including pastoral considerations, Bishop Perry said.

As chairman of the U.S. bishops' Subcommittee on African American Affairs, Bishop Perry has been a member of the Ad Hoc Committee Against Racism since its founding. The U.S. bishops' 2023 spring plenary assembly in June will be his first committee meeting as its leader, and he anticipates its members will identify immediate priorities then. He said his goals for the committee are "better understanding and better empathy."

"The whole push for this ad hoc committee is evangelization -- evangelization toward a deeper understanding and empathy with human dignity, broadly across the board," he said. "And that takes in all of us -- white, Black, brown, Middle Eastern, you name it."

Bishop Perry's leadership comes as U.S. Catholics are putting forward the causes of six African Americans for sainthood, including Father Augustus Tolton, for whose cause Bishop Perry is the diocesan postulator. Born into slavery in 1854 and ordained in 1886, Father Tolton was the first American Catholic priest known to be Black. He was declared venerable in 2019.

Meanwhile, thousands are flocking to rural Missouri to see the body of Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster, the African American foundress of the Benedictines of Mary, Queen of Apostles, whose body may be incorrupt, having recently been discovered little changed four years after her death and burial. Some are speculating that a cause may begin for her canonization as well.

For a long time in the U.S., the possibility of African American saints was not widely apparent, Bishop Perry said.

"If and when this (canonizing the first Black American saint) will happen, we will take our place alongside all other Catholic ethnicities that have their saints to date back centuries and millennia," he said. "We just did not have the people to champion our Catholic stalwart membership, and people who were living heroic lives despite the odds. No one brought that to the floor before. But these six candidates -- hopefully we can get them canonized -- will improve the impression of a lot of people, that yes, African Americans are as Catholic as anybody else, and they have their saints, too, their holy people who have suffered a great deal."

Bishop Perry said he is deeply grateful for the committee's two previous chairmen, Bishop Murry, who died in 2020, and Archbishop Fabre. "Both of these bishops really led it in a very, very inspiring way, and I think the bishops appreciate their service very much," he said. "We'll be picking up from there and seeing what we can do, as well."