In 1976, President Gerald Ford officially designated the month of February as Black History Month. In doing so, he called on all Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

This past year, Americans collectively turned their consciences and consciousness to the persistent obstacles and injustices that Black Americans face in pursuit of these accomplishments, as well as their ordinary, day-to-day obligations and activities.

The Catholic Church in the U.S. has also had to grapple with its own role in the history of these injustices, from slavery, to Reconstruction, to segregation, and civil rights battles. With a fresh perspective, many Catholics are assessing how parish life, religious education curricula, and catechesis can better represent the experiences and spiritualities of all of the Church’s members.

This renewed attention to the Black Catholic experience has also produced another fruit: “Black Catholics on the Road to Sainthood” (Our Sunday Visitor, $9.95), edited by Catholic writer Michael Heinlein, which chronicles the lives of six extraordinary men and women whose heroic stories are an important part of both American and Catholic history.

Though their circumstances differed — some were slaves, others the descendants of slaves, still others living as recently as the late 20th century — all six shared the deep pain of rejection by members of the body of Christ. This is what makes their holy lives so extraordinary: as Bishop Joseph N. Perry, auxiliary bishop of Chicago writes, they “persevered among us when there was no logical reason to do so.”

Their stories of self-sacrifice, devotion, and charity are living proof of what St. Paul calls “the folly of the cross.” Heinlein ensures that their witness can do nothing else but inspire fellow Christians to persevere in love even when facing the greatest of odds.

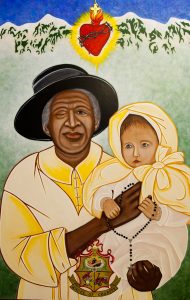

Servant of God Julia Greeley: A convert who used her freedom to help Denver's poor (Born circa 1835-1855, died 1918)

Born into slavery near Hannibal, Missouri, Julia Greeley never knew when she was born. She spent nearly a decade in St. Louis as a housekeeper for a prominent white family before gaining her freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation. The brutality of violence stayed with Greeley all her life; she bore a drooping eye that she received as the result of a beating.

In 1879, Greeley accompanied the family of Colorado’s territorial governor, William Gilpin, to Denver. With the help of Gilpin’s wife, Greeley fell in love with the Catholic faith. She converted at Denver’s Sacred Heart Church and immersed herself in the devotional and sacramental life of the Church.

She found great joy in her love for the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which she saw as the source for her many charitable and service-oriented ministries. She spread the devotion, even using it as a tool to evangelize Denver’s firemen by helping them to prepare for a sudden death.

Taking on odd jobs like cooking and cleaning, Greeley used her meager salary to finance a ministry to the poor. Wearing her trademark floppy hat, Greeley dragged a red wagon filled with food and goods to distribute to the poor.

When Greeley heard that young women of the parish were not coming to the parish youth activities because they had nothing nice to wear, she went begging for hand-me-downs from well-to-do families.

Greeley regularly cared for the sick, often telling caretakers to take rest for themselves. She helped bury the dead. She even gave her own grave away to keep an elderly Black man from a poor man’s plot.

It is amazing to consider all that she did, even while suffering from painful arthritis and blatant episodes of racism. Once a group of women claimed that Greeley’s poor wardrobe should have made her ineligible to rent a pew in the front of the Church. Another time, a religious sister told Greeley that in heaven “she would be as white as the angels on the altar at Sacred Heart Church.” Greeley bore these pains in her heart and never challenged or returned any such insults.

Many of those Greeley helped were not even aware it was she who came to their aid; she conducted works of mercy under the cover of darkness. Only after her death did they come to know of all she was secretly doing to build God’s kingdom. Greeley died on June 7, 1918, which that year fell on the feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Her canonization cause was opened in 2016, held up by Denver Archbishop Samuel J. Aquila as a model of mercy in the Jubilee Year of Mercy. Her remains were moved to Denver’s Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception the following year.

Servant of God Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange: A model of holiness in times of plague and racial strife (1784-1882)

Little is known about Elizabeth Lange’s early years. Likely born in Santiago de Cuba, she was known to be of African descent, though she once described herself as “French to my soul.” She immigrated to the U.S., probably in part due to an 1808 government mandate for non-Spanish Cuban residents to swear loyalty to the Spanish king.

Lange settled in Baltimore, where she offered free education for African American children out of her home at a time when no such education existed in Maryland.

In 1828, Lange was persuaded by Sulpician Father James Joubert to start a school serving girls of color. Along with her friend, Magdaleine Balas, Lange accepted the challenge. Eventually, Father Joubert decided it would be best to inaugurate a women’s congregation of religious sisters to operate the school. And with that, the Oblate Sisters of Providence became a reality at a time when there was no convent in the country willing to accept women of color.

With Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange as the first superior, the Oblate Sisters of Providence were established in 1829, the first successful congregation for African American women in the United States. With Mother Lange’s pioneering vision and holy example, the Oblate sisters persevered through great difficulties and offered their lives in service to all in need, especially to pupils, orphans and widows, the sick, and those in spiritual need.

They faced many obstacles, not the least of which were some Catholics who believed “colored” women should not wear a religious habit. In a short time, however, the community and its apostolate grew.

Mother Lange’s care for the less fortunate and marginalized knew no bounds. In 1832, when Baltimore was struck with a cholera epidemic, Mother Lange and several other sisters offered to care for victims of the mysterious disease. And she bore her own difficulties with an abiding trust in God’s will.

There are few known details about Mother Lange’s later years. She spent many of them ill, typically confined to her room. Despite the odds and no matter the obstacle, Mother Lange consistently persevered while trusting in God’s provident hand.

Mother Lange died on Feb. 3, 1882. A cause of canonization formally was opened in 1991, and her earthly remains were relocated to the motherhouse chapel of the Oblate Sisters of Providence in 2013.

Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman: A prophetic voice for the modern Church in the U.S. (1937-1990)

Born in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in 1937, Bertha Bowman was the granddaughter of a slave and the only child of a doctor and a teacher. Bowman experienced prejudice and racism growing up, but was taught “we must return love, no matter what.”

Her life of discipleship began in the Methodist church, where she was raised in the Black spiritual tradition. Her experiences gave her a foundation of faith to endure the sufferings of a segregated South.

The course of Bowman’s life changed when a school open to Black children was opened up in her Mississippi hometown by the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration from La Crosse, Wisconsin.

The gospel joyfulness of the missionaries attracted young Bowman to the Catholic faith, and she converted at age 9. The attraction to their way of life was so strong that at 15, she asked to be an aspirant in their order. After taking religious vows, she went by the name Sister Thea.

Sister Thea left Mississippi for Washington, D.C., in 1965 after several teaching assignments. There, she obtained a master’s and doctoral degrees in English at The Catholic University of America. In 1972, Sister Thea returned to La Crosse to take up a professorship at Viterbo College.

Sister Thea also served as director for intercultural affairs in the Diocese of Jackson. She was a founding faculty member and later director of the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University in New Orleans.

She came of age in the midst of America’s struggle for civil rights and recognized the need not only to speak up on behalf of her African American brothers and sisters, but to help heal a society, culture, and Church deeply wounded by racism and its consequences.

As a writer, teacher, musician, and evangelist, Sister Thea preached the gospel to clergy and laity alike, promoting ecclesial and cultural harmony and reconciliation. With her prophetic voice, she was a tireless spokeswoman for the Black Catholic experience.

In 1984, after burying both of her parents, Sister Thea was also diagnosed with breast cancer. Though weakened by treatment, her mind and heart remained strong. Pledging to “live until I die,” Sister Thea remained committed to her ministry, which included travels around the world.

About a year before she died, Sister Thea gave a rousing speech before the bishops of the U.S., articulating for them the Black Catholic experience in this country and the need for their fuller participation in the life of the Church.

She died March 30, 1990, and her cause for canonization was opened in 2018.

Venerable Father Augustus Tolton: A famous first who took the last place (1854-1897)

Father Augustus Tolton, born the son of slaves on April 1, 1854, became the first priest from the United States who was recognizably African American. After narrowly escaping slavery in Missouri with his mother and siblings, he reached maturity in Quincy, Illinois. There, the local pastor accepted him into the parish school despite opposition from parishioners.

Tolton knew God was calling him to be a priest, but since no American seminary would accept him, he was forced to work arduous, low-level jobs instead. Meanwhile, he pressed on toward his calling.

Tolton was accepted to seminary in Rome and was ordained in 1886. Though he expected to serve as a missionary in Africa, he soon found out that he was destined for service back in the United States.

“America has been called the most enlightened nation; we will see if it deserves that honor,” said Cardinal Giovanni Simeoni, prefect of the Holy See’s Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. “If America has never seen a Black priest, it has to see one now.”

Father Tolton was sent back to Quincy, where he was met with racial prejudice by laity and clergy alike. He was maligned and mistreated by many, including his own brother priests.

Father Tolton accepted this cross. But given the situation, he was invited to minister in Chicago in 1889 after requesting a transfer there. This request was not so much made to make his life easier as to allow his ministry to be more effective.

In Chicago, Father Tolton was indefatigable in his efforts to serve a growing Black Catholic community and establish St. Monica Church for Black Catholics. This work, combined with a good deal of travel for speaking engagements on the plight of his people, took a toll on the priest. After returning from a retreat by train, Father Tolton collapsed on a Chicago street corner in record-breaking heat on July 9, 1897, and he died shortly thereafter.

Father Tolton’s legacy has loomed large in the 12 decades since his death. Chicago Auxiliary Bishop Joseph N. Perry, the vice-postulator of Father Tolton’s cause, writes that Father Tolton “rises wonderfully as a Christ-figure, never uttering a harsh word about anyone or anything while being thrown one disappointment after another.”

Father Tolton, the bishop added, “persevered among us when there was no logical reason to do so.”

Servant of God Mother Henriette Delille: A teacher who wasn't afraid to break the rules (1812-1862)

Born in 1812 and raised Catholic in New Orleans, Henriette Delille was the fourth generation of freedmen. Delille’s family expected her to marry a white man, which would afford them all a better life than if she married a Black man. Records indicate Delille entered into such a relationship but that it did not last long. It produced two children who both died in infancy. Just past 20 years of age, Delille found herself surrounded by grief and hardship.

In 1834, Delille experienced a conversion, and she decided to enter religious life. Unfortunately, many religious communities in the United States did not allow Black women to enter their convents. Delille applied to the Ursuline convent and the Carmelite community, but was denied entrance on the basis of her skin color.

She attempted to found an interracial community with a white woman, but her efforts were shut down by Church leaders who did not think it was appropriate for black and white women to live together in religious life.

Her desire for religious life and apostolic zeal brought her closer to like-minded friends, Juliette and Josephine. Together they ministered to enslaved and free girls and women of color. Laying the foundation for a new order, which at the time was known as the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, she wrote their rule of life in 1836.

Taking the religious name Marie Terese, Mother Delille took upon herself a task of reforming religious life, much like her inspiration, St. Teresa of Ávila.

By the 1850s, Mother Delille’s community had a convent with classrooms, operated an orphanage, and educated young girls in literacy and catechism while teaching them skills like sewing, which was outlawed. The education they provided to enslaved children was also outlawed at the time. Their service to the sick included the victims of a yellow fever epidemic, and they also brought into their home elderly infirm women, a first in America.

Mother Delille’s generosity and love was known to everyone who knew her. She responded to the Lord’s call with great love, requisite perseverance, and heroic virtue. The last decade of her life was dedicated to attracting new members to the congregation. At the time of her death, 12 sisters of varied racial descents resided at the convent.

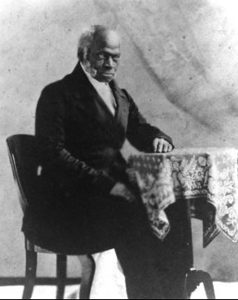

Venerable Pierre Toussaint: A freed slave who gave his life for the poor of New York (1766-1853)

Pierre Toussaint was a living precursor to what the Second Vatican Council taught regarding the universal call to holiness. Born a slave in Haiti, Toussaint came to New York as property of a French Haitian Bérard family, which later freed him in 1807.

Toussaint established himself as a successful hairdresser at the service of New York’s upper crust. Taking his gospel call seriously, Toussaint found ways to speak about his faith both explicitly and implicitly. Many patrons, friends, and neighbors benefitted from Toussaint’s counsel.

Toussaint gained a sizable salary, much of which he put toward a lifelong mission of charity. With his wealth, he purchased his sister’s freedom as well as that of his future wife, Juliette. After they wed in 1811, Juliette and Pierre spent their lives together in service to the poor and needy.

Although the Toussaints did not have any children of their own, they adopted Pierre’s niece Euphemie. The couple took in boarders and orphans, funded orphanages, operated a credit bureau, helped the unemployed develop skills and find work, and established hostels for priests and refugees.

They were generous in the support of ecclesial institutions and were longtime benefactors of religious communities. Toussaint attended to the needs of the sick and suffering. When epidemics hit the city, Toussaint remained to help care for the afflicted and dying.

A daily Mass attendee for more than 60 years, Toussaint was a longtime parishioner at New York’s first parish, St. Peter’s. Each day he walked the streets to church while being passed by carriages and street cars that would not transport him because of the color of his skin. Rather than becoming embittered by the hardships he endured because of his race and his Catholic faith, the model layman only gave more.

Toussaint died on June 30, 1854. In 1990, his remains were moved to St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. Not only is he the only layman to have been afforded this opportunity, it is also a poetic postscript to the life of a man whose race once prohibited him from entering the city’s Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Pierre Toussaint was declared venerable by Pope St. John Paul II in 1996.