The iconic pop artist had a complicated relationship with the Church. But the Catholic faith was essential to his art.

“In the future everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes.” — Andy Warhol

The Art Newspaper broke the story in late January: “Vatican to host major Andy Warhol exhibition.”

If all goes according to plan, the show will launch in 2019, simultaneously at the Vatican Museums in Rome and the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. In the follow-up, media noted the many ironies and incongruities in the story.

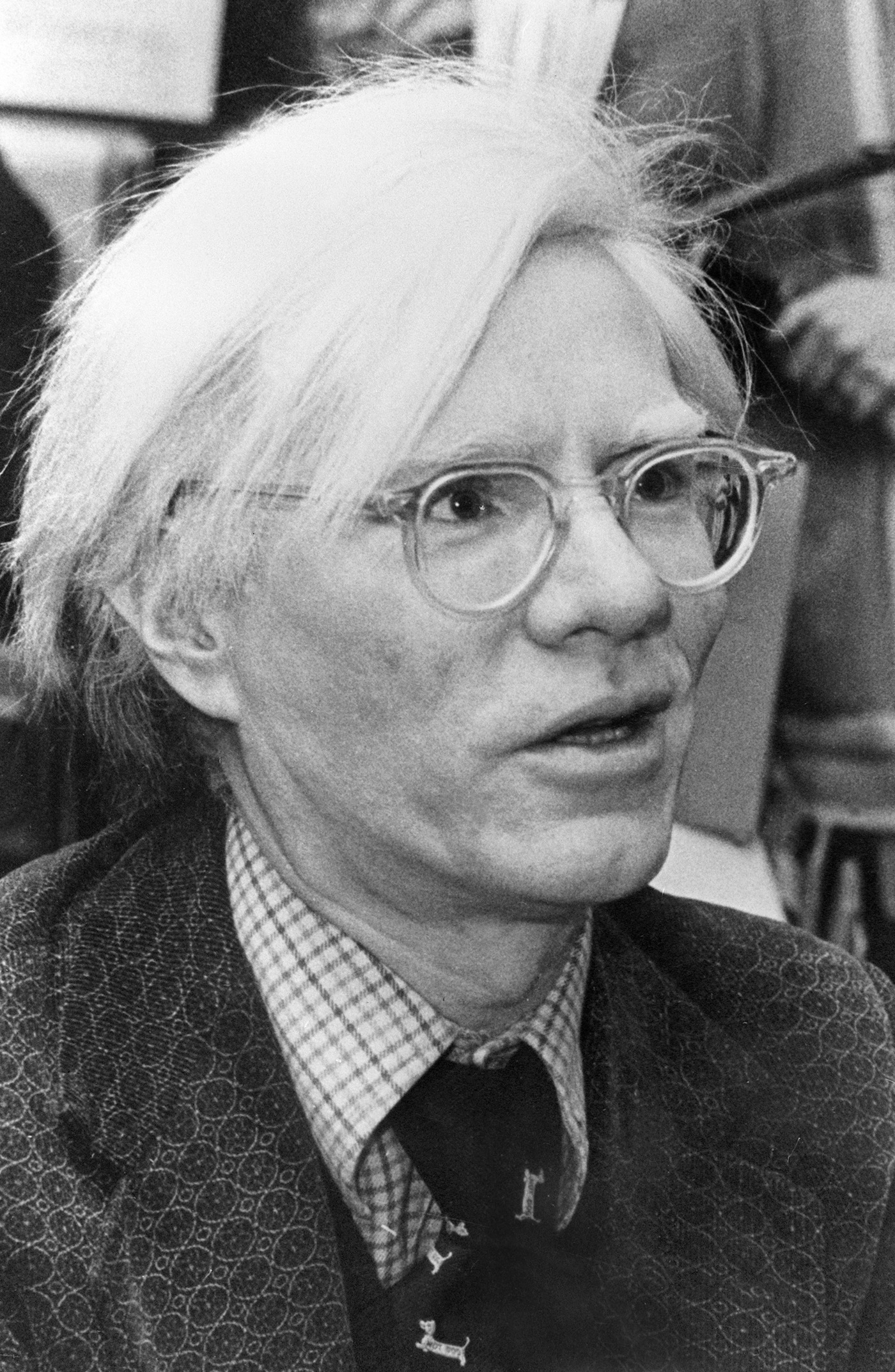

Warhol produced an enormous body of art — paintings, movies and prints — in his relatively short life (1928-1987). He was profoundly influential not only in art, but also in entertainment, fashion, graphic design and marketing.

So much of the “look” of U.S. and European culture since the 1960s bears the mark of Warhol. Photo-editing software now comes standard with filters that render snapshots in his distinctive style.

Some of his best-known works, however, were porn flicks whose titles can’t appear in a religious magazine. And he would sometimes require, as the price of admission to his studio, the right to photograph each entrant’s genitals.

Yet, as all the recent commentators have noted, he was Catholic. In various reports, he has been described as “devout,” “practicing,” “observant,” “churchgoing,” and even a “daily communicant.” Some of the adjectives are more accurate than others.

What’s certain is that Warhol was as serious about his faith as he was about anything. What’s debatable is how serious he was about anything.

Working-class family

His childhood had ample gravity for a lifetime. He was born to immigrant laborers, Andrew and Julia Warhola, and grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Pittsburgh. He was the youngest of the couple’s three sons (their firstborn child, a daughter, died in infancy).

Warhol was often sick as a child. He suffered with Sydenham chorea (St. Vitus’ dance) and had three nervous breakdowns before his 11th birthday.

His home life was loving and devout. His parents were Byzantine Catholics from what is now northeastern Slovakia. Julia decorated their home with icons and holy cards.

It was the children’s custom to drop to their knees and pray with their mother before they left the house each day. Every Sunday the family walked more than a mile to the divine liturgy at St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church.

Warhol was artistic, precociously intelligent and sensitive. He loved media. He developed ways to project the newspaper comics onto walls. He loved movies, and he wrote to Shirley Temple, who sent him an autograph.

When he was in his early teens, his father died. Neither of his brothers had gone to college, but the family resolved that he should get an education. He studied art at Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, selling fruit on the street to help pay his way.

Graduating in 1949, he moved to New York City to find work as a commercial artist. He dropped the “a” from the end of his name as a kind of break with his past. But, as soon as he was able, he sent for his mother to join him in Manhattan. She lived with him from 1951 till 1971, and mother and son continued the practice of praying together. Julia went to daily Mass, and he often joined her.

His career soared, and he was much in demand as an illustrator for advertisements and product packaging. Women’s shoes were his specialty.

He also began to venture into fine art. In 1956, Warhol’s drawings were shown at the Museum of Modern Art. Soon he found his place in the emerging Pop Art movement, whose practitioners took their inspiration from popular culture — advertising, comics and product labels.

In the early 1960s, Warhol gained notice for a series of paintings, each depicting a can of Campbell’s Soup — 32 paintings for the 32 varieties then available. He would go on to produce similar presentations of Coke bottles, Brillo cartons, S&H Green Stamps and other familiar items.

Like some other famous artists in the Pop Art movement, Warhol was gay. Unlike his colleagues, however, he made no effort to hide it. Indeed, he enjoyed playing up to stereotypes — “coming on swish,” as he put it — in order to see how it discomfited people. (His friends say that he would later use his Catholicism in the same way.)

Success led to more success. He experimented in other media, including cinema, and from 1963 through 1968 he produced hundreds of “underground” films. Many were edgy in content and graphically sexual.

He attracted young actors, male and female, to The Factory, his studio in Greenwich Village. The most promising and beautiful he promoted as his “superstars.”

The Factory developed a reputation for freewheeling sex and heavy drug use. As the ’60s wore on, some of the studio’s stars and hangers-on crashed spectacularly. There were suicides and overdoses.

But the tape kept rolling and the camera flashing as Andy recorded the happenings.

Point of absurdity

Warhol was a satirist, and his method was to take things that were common, mundane and banal — and then magnify and multiply them to the point of absurdity. He painted Coke bottles on an epic scale. He covered colossal canvases with rows of uniform, mass-produced items.

He satirized Hollywood for its mass-market entertainment. One of his famous early works was a publicity shot for an Elvis movie, reproduced multiple times on canvas. He produced “Double Elvis,” “Triple Elvis,” and “Eight Elvises,” among others.

As his reputation grew, he became increasingly one with what he satirized. He was immediately recognizable in his trademark blonde wig and plastic-framed eyeglasses. He was an A-list celebrity, and he embraced the role. Pop, for him, became more than an approach to art. It was a way of life — passive, consumerist and superficial.

Now he didn’t simply satirize fame. He desired it with a passion bordering on desperation. In his diary he would obsessively note which celebrities invited him to parties from year to year, and he pronounced maledictions if they dropped him. He seethed with envy for invitees who replaced him, especially if they were gay.

He craved the company of other celebrities, and those he most admired were Catholic: Jackie Onassis, Martin Scorsese, Bianca Jagger. He held Catholics to a higher moral standard. In his diary he records severe judgments of Scorsese for his divorce and remarriage. Another Catholic he scolds for making anti-Semitic remarks.

He often traveled with an entourage, and most of the members of his inner circle were Catholic. The artist Christopher Makos recalled in his memoirs: “He may have related better to us Catholics because we all have the same background: Mass, priests, nuns, Catholic school, a sense of guilt. His religion was a very private part of his life.”

It became suddenly more important to him in 1968, when he was shot — almost fatally — by a deranged woman who had tried to sell him a movie script. As he lay bleeding in the hospital, he promised God to be regular about churchgoing if he survived.

He kept his promise. Probably the phrase that appears most often in his diary is “Went to Church” (or its near equivalents, such as “Went to Mass”).

He made sure to get to St. Vincent Ferrer, his parish church, on Sundays, though he usually dropped in between the regularly scheduled services. When he did attend Mass, he did not receive communion. In fact, he usually made his exit before the Sign of Peace, which he disliked.

In addition to his Sunday visits, he also dropped in frequently during the week, just to pray. His pastor at St. Vincent confirmed his attendance, in interviews with Warhol’s biographers, and also his abstention from Communion. He added that the artist’s lifestyle was “absolutely irreconcilable” with Catholic moral doctrine.

From painting to publishing

In 1969, Warhol took up a new medium as he launched Interview magazine, a gossipy celebrity-talk monthly. He found his ideal editor in Bob Colacello, previously a film critic for The Village Voice. Colacello captured the artist’s attention with a review that called Warhol’s most recent movie a “great Roman Catholic masterpiece.”

Colacello accompanied Warhol to parties and clubs in Manhattan, but also on his international jaunts. On a trip to Mexico, Warhol insisted that they visit the shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City.

In his memoirs, Colacello recalled that Warhol did “all the Catholic things” — taking holy water, genuflecting, kneeling, praying, making the sign of the cross. He concluded: “I realized then that his religion wasn’t an act.”

“His religion” moved Warhol, in fact, to take up charitable works. He quietly volunteered at the soup kitchen run by the Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest. He made it a point to spend his holidays, Christmas and Thanksgiving there with New York’s homeless.

He poured coffee and sat to talk with the clients. Sometimes he brought friends to serve with him. When one friend had an emotional tirade at the soup kitchen, Warhol reminded him, “Victor, we’re here because we want to be here.”

When in Rome, in 1980, Warhol attended a papal audience and met briefly with Pope John Paul II, receiving his blessing.

His nephews recalled that when they visited Uncle Andy in New York, he knelt and prayed with them before they left his townhouse, just as Julia had always done with her children.

His religion seems to have left other areas of his life untouched. Some members of his inner circle say that he refrained from sexual contact, but enjoyed watching others having sex — and filming and photographing them while they did. Colacello and others believe he was a sadist-voyeur.

Warhol exploited his superstars as they crashed and burned from their addictions and mental illnesses. He directed them to act immorally while he watched (and the world watched). Later, privately, he would mock them and gossip about them.

The art historian John Richardson — a friend who was also Catholic and also gay — excused Warhol’s behavior by calling him a “recording angel,” who “held the most revealing mirror up to his generation.”

Warhol did that, but he wasn’t simply a passive observer. It is hard to deny the moral agency of an artist who was so mixed up in his art, as both satirist and self-satirized.

Death’s inevitability

After surviving the attempt on his life, Warhol’s art took a turn perhaps more serious. He painted a series of skull paintings, mass-produced as always, an insistent reminder of the inevitability of death.

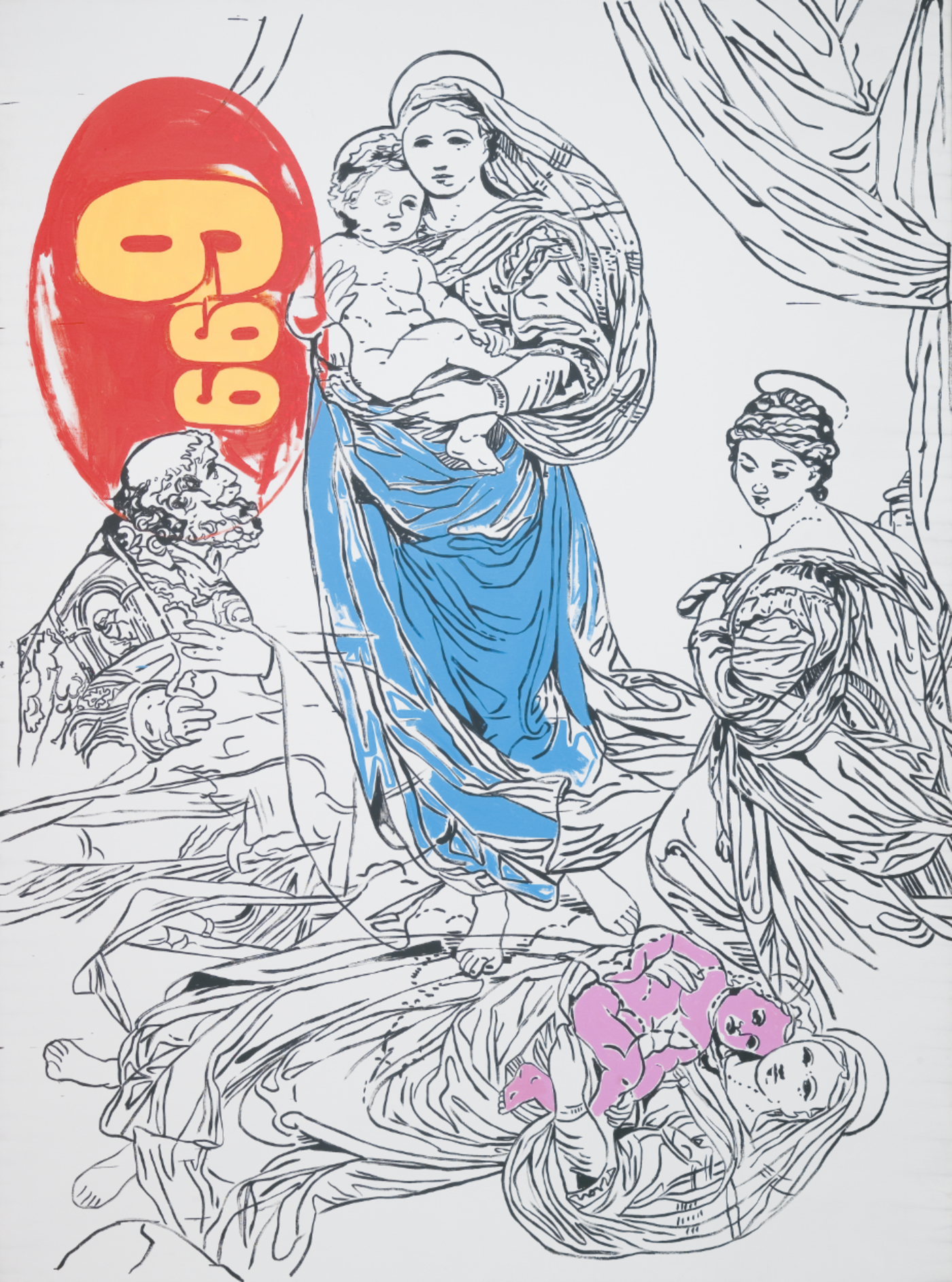

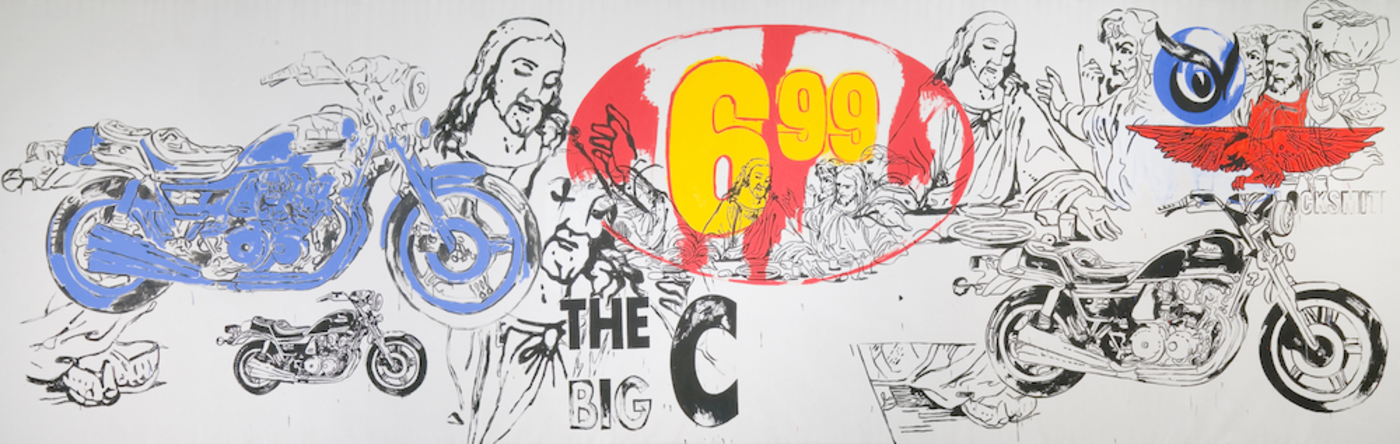

He also began to produce overtly religious art. The final series he undertook was based on a low-quality reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper.” He did it in red and in camouflage. In some versions he overlaid the scene with packaging elements from Dove soap, GE lightbulbs, and Wise snack foods — all brands whose names have religious overtones.

The series was shown in cities all over the world, including Milan, the site of Leonardo da Vinci’s original.

While accompanying his works to exhibits in Europe, he suffered nausea and abdominal pain. The problems continued, but he avoided conventional medical treatment — opting instead for the application of healing crystals. Since his childhood illnesses, he had had a fear of hospitals and doctors.

By early 1987 it was clear he would need surgery. His doctors described the operation as “routine,” but Warhol’s heart gave out shortly afterward. He was 58.

He was buried in Pittsburgh after traditional funeral rites at his childhood church. On April 1 of that year, New York’s St. Patrick Cathedral hosted a memorial service for him. Sir John Richardson delivered a eulogy that focused entirely on Warhol’s religious commitments.

He credited the artist with at least one conversion to Catholicism and cited his church attendance and charitable work. Richardson’s eulogy has become the ur-source of all subsequent efforts to present Warhol the Artist as Warhol the Saint. It’s a hard sell. His closest associates remember him as cruel, shallow and exploitative.

To his credit, however, he never claimed to be a saint. And he never claimed to be the wronged party in his complicated relationship with Catholicism.

He never acted as if the Church owed him an apology, or a change of doctrine, or Holy Communion. He had little use for angry ex-Catholics, and he found their mean-nun anecdotes to be tiresome.

The church he took the trouble to visit — many times a week — was his mother’s church. His pastor preached clearly against the lifestyle to which Warhol clung. It seemed to make little practical difference in his life; but he kept returning. And the face of Jesus began to haunt his art — appearing, like the earlier S&H Green Stamps, more than a hundred times on a single canvas.

Pop goes the sacred

Scholars note the similarities between Warhol’s art and the traditional Byzantine icons of his childhood. He favored gold backgrounds and flattened human figures. His images of Elizabeth Taylor and Jacqueline Kennedy have been compared to Madonnas.

His repeated motifs are like the multiple Hail Marys in the rosary. Like icons, Warhol’s artworks are not historically accurate, but symbolically rich. Where the iconographers used books, birds and buildings, Warhol used product logos.

If Christ is Light of the World, Warhol presents him with the logo from General Electric lightbulbs. If the Redeemer embodies divine wisdom, Warhol portrays him with the Wise potato-chip logo. If Christ receives the Holy Spirit as a dove, Andy borrows his dove from a package of soap.

What did he intend by doing this? He wouldn’t say. Some critics held that he was intentionally cheapening Christian art — mocking the sacred.

Others interpreted his work as commentary on the modern world’s tendency to cheapen everything through mass production, turning even sacred persons and ideas into marketable commodities. Still others held he was expressing devotion in the way that came naturally to a pop artist.

Mike Aquilina is a contributing editor of Angelus News and the author of more than 40 books, including “Keeping Mary Close: Devotion to Our Lady through the Ages”

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.