The fiction and poetry of the Beat movement have arguably never been more popular.

The Beats emerged in the 1940s and ’50s as a party of rebellion and resistance. The country was settling into prosperity and relative peace after the successive trials of the Great Depression and World War II.

But what others called “peace” the Beats saw as complacency and conformity, and they raged against it — dropping out of society, hitchhiking across the continent, abusing drugs, and flouting the established norms for everything from sexual morality to punctuation.

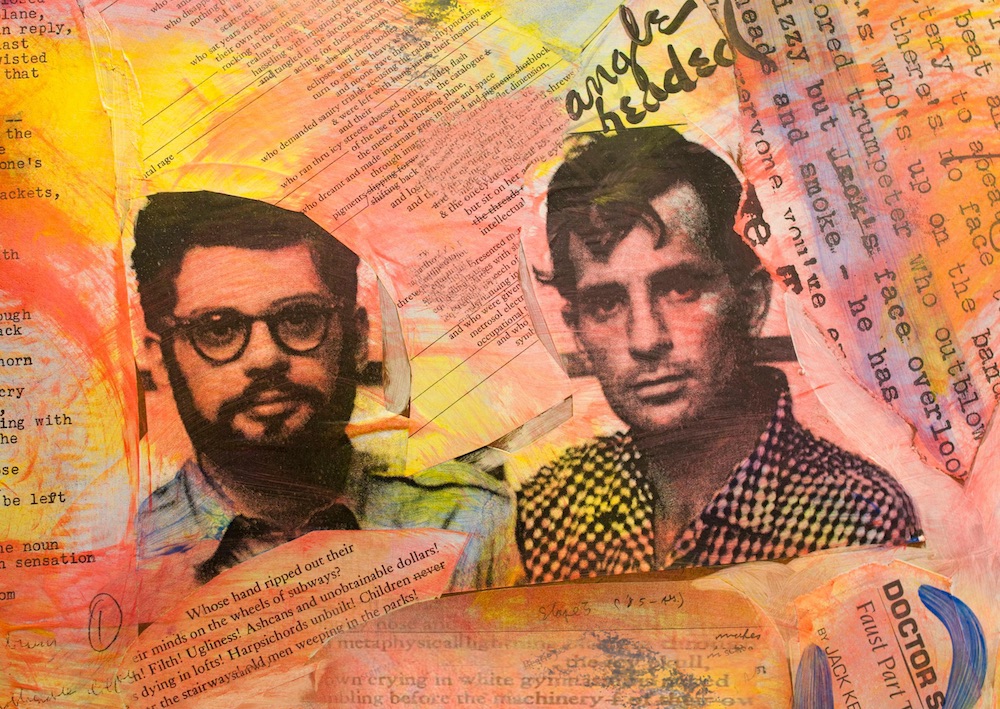

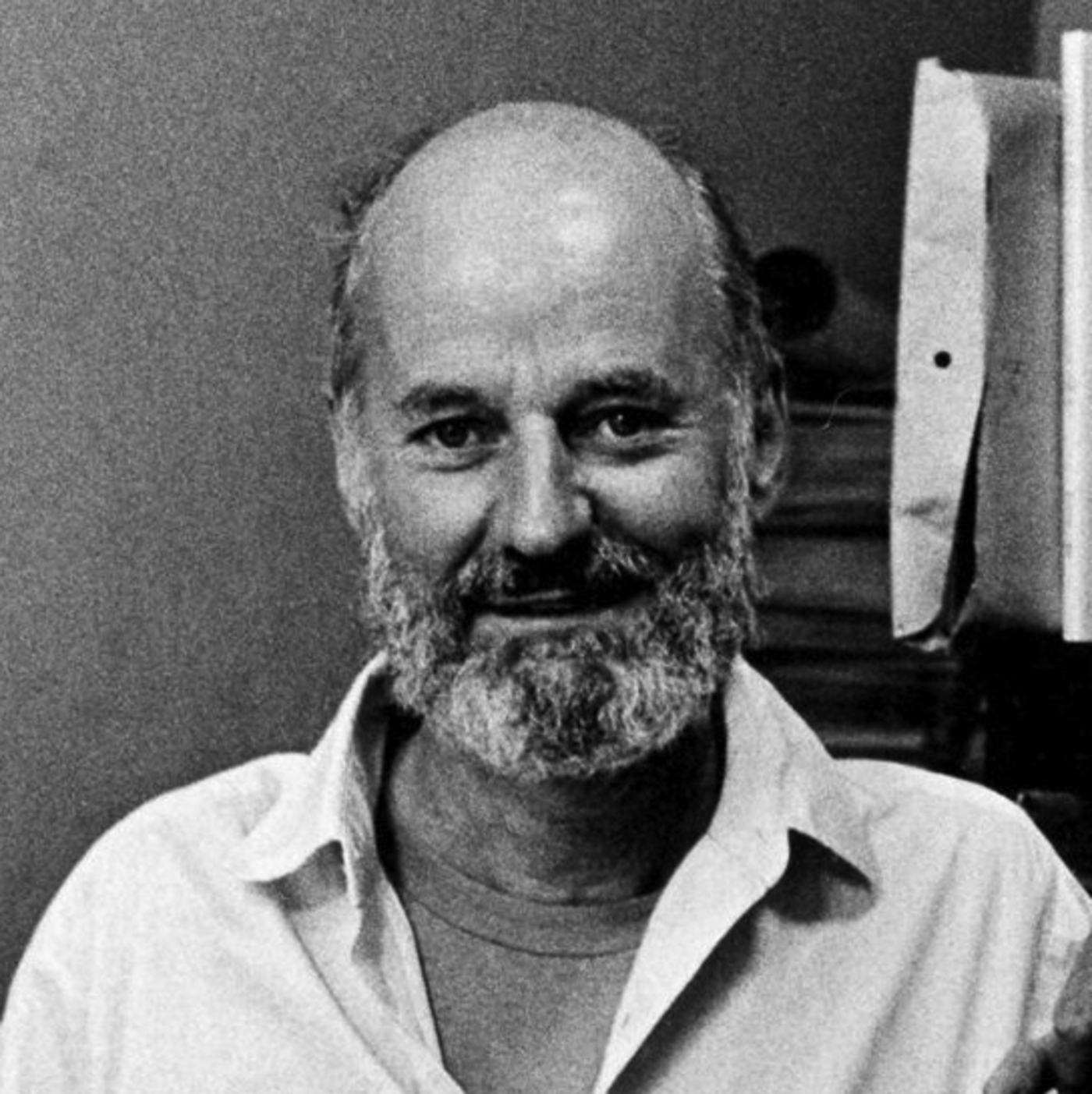

They reported their adventures in barely fictionalized form. Beat was to literature what bop was to music: a new style, spontaneous, improvisatory, exuberant, and ecstatic. Among the movement’s most prominent authors were Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, William S. Burroughs, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Beat literature was at once a cry from the depths — a howl — and a desperate reach for a transcendent high.

From the beginning, moreover, it was consciously religious, and its dominant religious influence was, oddly enough, Roman Catholicism.

The core members of the movement — Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs — met at Columbia University toward the end of World War II. They wrote much, but their work met with little success. They gained notice, however, as a bohemian presence in New York City, an underground collective.

Kerouac gave them their name, when he referred to them as a “Beat Generation.” He used “beat” originally to mean “exhausted,” “fatigued,” “defeated” — beaten down — but he later came to associate it with “beatific,” the peculiarly Catholic term for the state of the saints in heaven.

Both connotations were intentional. The authors of the movement were “beat down” by society, but deeply wanting to get “beatitude” by any means available.

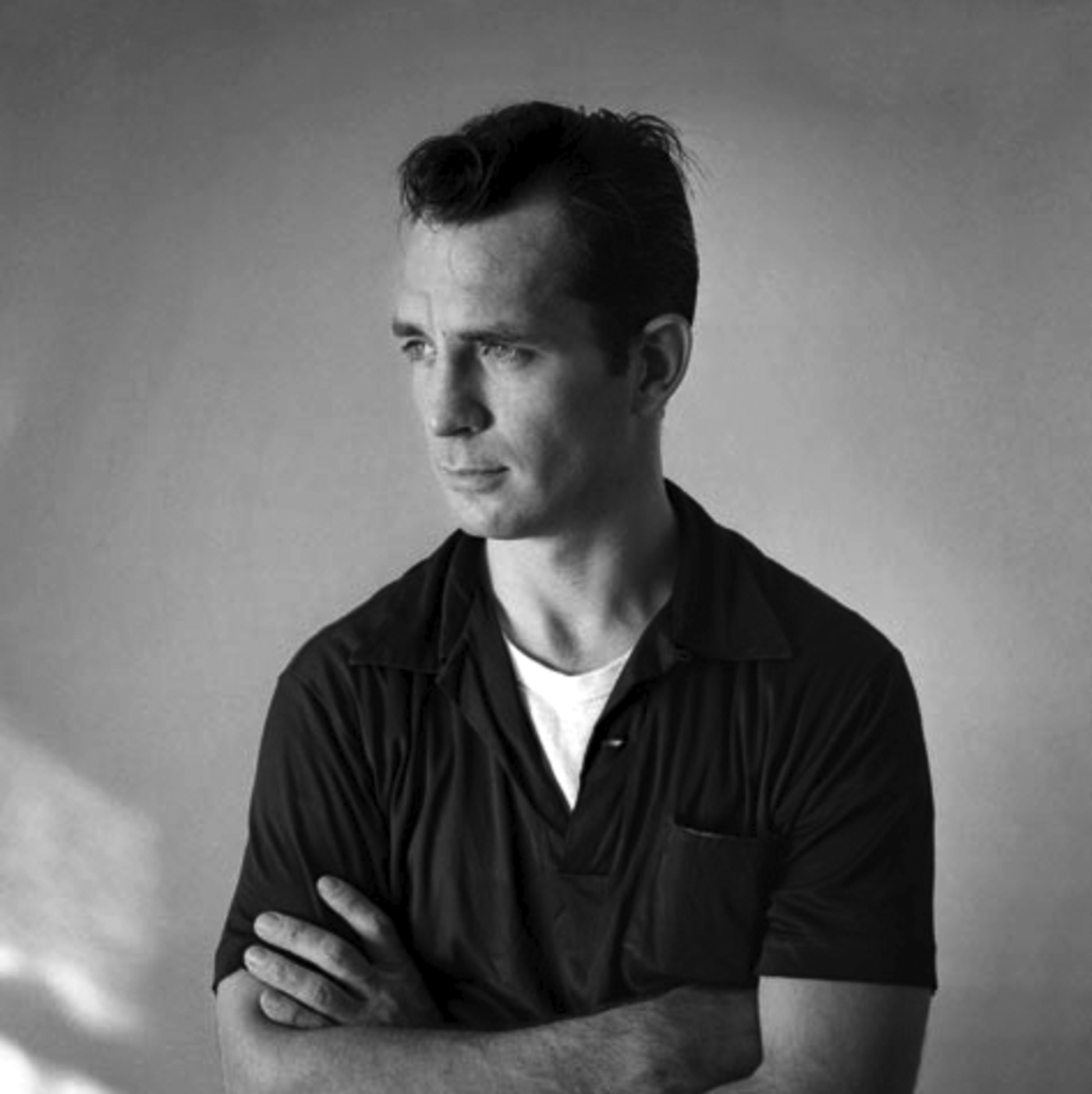

Kerouac saw his mission as a writer in religious terms. He was born in 1922 and raised in a devoutly Catholic French-American home in Lowell, Massachusetts. His name at baptism was Jean-Louis. When he was 4 years old, his older brother Gerard died of rheumatic fever. Afterward his mother, encouraged by the religious sisters in the parish, venerated Gerard as a saint. His father, however, lost his faith and grew anticlerical.

The young Kerouac seemed to have inherited equal parts of his mother and father. He reported having mystical experiences from early childhood. But he stopped attending Mass in his teen years, and he never went back.

Yet, like his mother, he kept a lively devotion to Jesus. In adulthood, he habitually began his writing sessions by praying to Jesus and reading from the Bible.

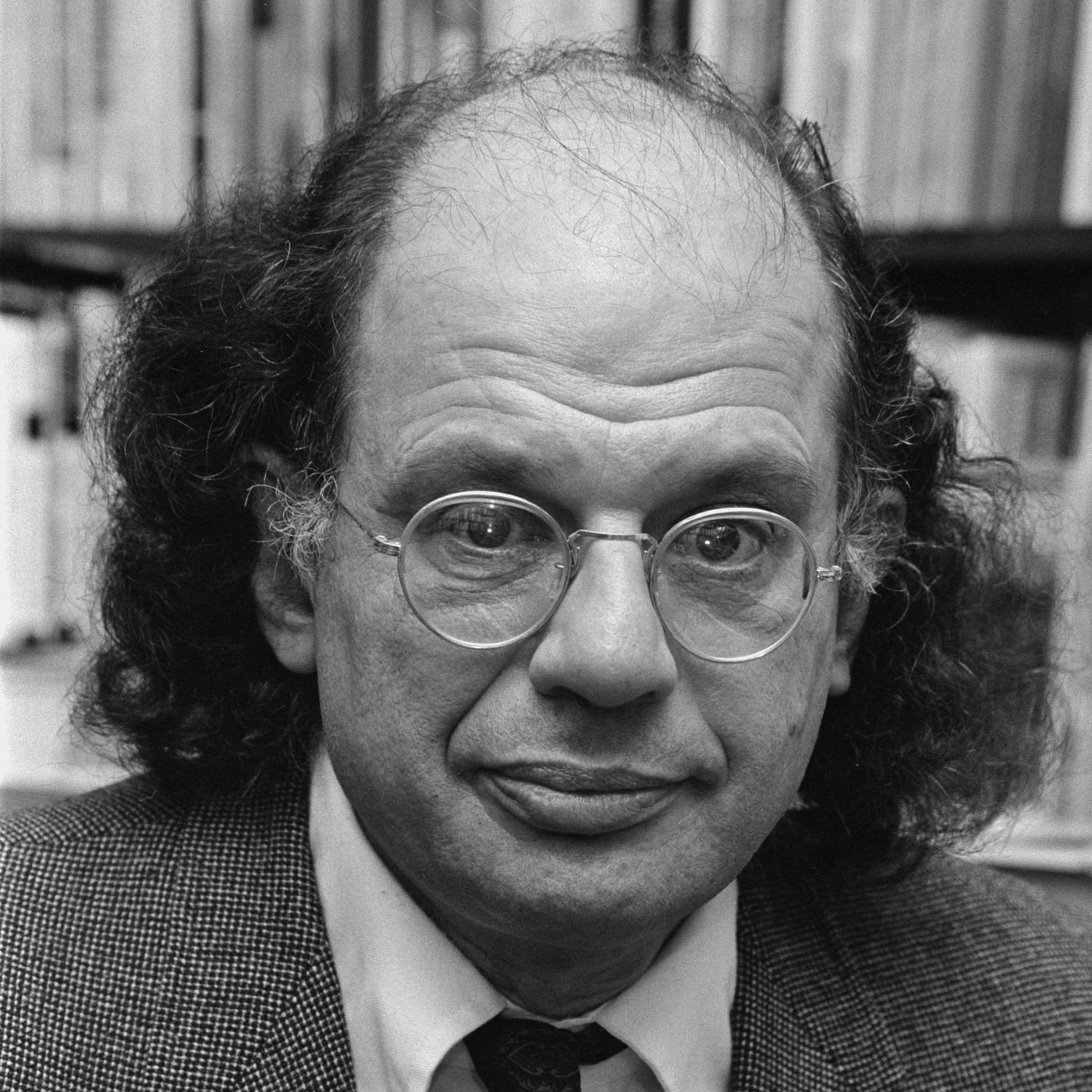

He also read the classic works of Christian mysticism and shared them with the other Beat authors. Allen Ginsberg, a Jew, was drawn especially to St. Teresa of Ávila and the 17th-century British Catholic poet Richard Crashaw.

Other religious influences pressed upon Kerouac and his friends. There was, in America, a growing interest in Eastern traditions, and Kerouac took up the study of Buddhism. In his poems and fiction he sometimes imitated Buddhist forms. In his journals and letters, Jesus and Buddha seem to vie for his soul.

Kerouac was capable of filling pages with tender piety for Jesus, but he could also fill pages with blasphemy, comparing Jesus to Buddha and finding the Christ wanting in many respects.

Much of his ranting was influenced more by alcohol than by meditation. Kerouac was a heavy drinker from his youth, and he found writing and social situations impossible to navigate without the help of a bottle.

He took drugs as well — smoked marijuana and popped amphetamines. And he observed none of the sexual discipline commanded by Jesus or recommended by Buddha. He had two marriages in the 1950s, but was unfaithful to both wives. He pursued sexual encounters mostly with other women, but also with men.

He traveled often, hitchhiking west and to Mexico with Neal Cassady, a high-spirited dropout and ex-con — and fellow lapsed Catholic — who became a sort of muse to the Beat movement. Cassady had intermittent sexual relationships with both Kerouac and Ginsberg.

Kerouac wrote it all down, first in his journals, but gradually he drew material from the journals to build novels.

The Beats’ first small successes came with the new decade. Kerouac’s novel “The Town and the City” appeared in 1950 to moderate critical praise.

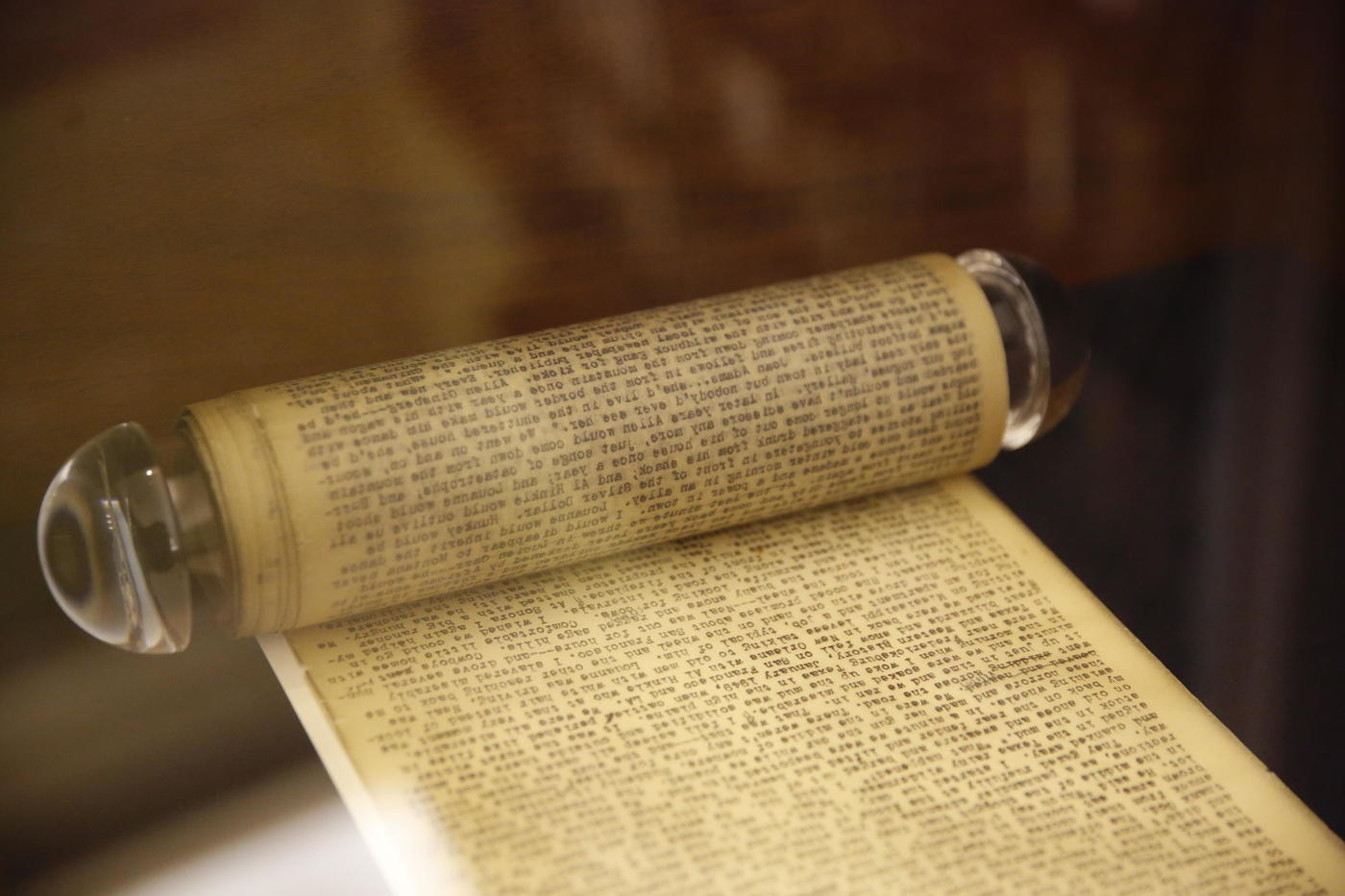

Literary stardom arrived with the publication of “On the Road” in 1957. He had drafted the novel in 1951 in a three-week spree of almost round-the-clock writing fueled by Benzedrine and coffee. He fed a continuous roll of Teletype paper into his typewriter, so that he would never be interrupted by the end of a page.

Allen Ginsberg was meanwhile achieving his own notoriety. He had moved to San Francisco in 1954 and established the city as a center of Beat writing. In 1956 he published his long poem “Howl,” whose opening line is a gloss on Kerouac’s initial intuition of Beatness, both beat down and beatific: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical …”

“Howl” appeared in print in 1956, published by City Lights Bookshop, which was owned by the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. As a publishing imprint, City Lights would become closely identified with the Beats.

Ginsberg’s debut ended abruptly when city police and U.S. customs officials seized the publisher’s stock of the book and charged Ferlinghetti with obscenity. But that was the kind of publicity that made fame, and sales of “Howl” soared when the court ruled in favor of Ferlinghetti.

By the end of 1957, both Ginsberg and Kerouac had achieved instant celebrity, even appearing in the news and on television talk shows. Ferlinghetti’s second book of poems, “A Coney Island of the Mind,” appeared in 1958 and quickly became one of the best-selling poetry collections in history.

The word “beatnik” entered the national vocabulary, and the authors began to influence not only mainstream literature, but also fashion. The Beatles took their name from the movement.

“Howl” was a rant — a breathless tirade against conformity, a celebration of transgressive behavior.

“On the Road” was a different kind of art. It was manic, but lyrical and affirming. According to Kerouac, the book “was really a story about two Catholic buddies roaming the country in search of God. And we found him.”

Though the narrative turns on episodes of drunkenness and promiscuity, the book’s climax is a visionary moment when the narrator, Sal Paradise (a barely disguised Kerouac), says, “And of course no one can tell us that there is no God. We’ve passed through all forms. Everything is fine, God exists, we know time.”

Paradise, whose name is no accident, is a man in search of meaning. He wants to upend the banality that passes for postwar peace. His vision is a rejection of trendy nihilism and a grasping for transcendence in God.

Indeed, the work of both Ginsberg and Kerouac drew its energy from religious language and imagery. Their vocabulary, from the name Beat onward, was largely religious, shot through with “angels,” “saints,” “glory” and “God.” In his 1956 poem “America” Ginsberg wrote, among other observations:

America when will you be angelic? …

You made me want to be a saint. …

I have mystical visions and cosmic vibrations…

America how can I write a holy litany in your silly mood?

Kerouac’s fiction after “On the Road” became more overtly religious. And the author seemed gradually to resolve the struggle between Buddha and Jesus — in favor of Jesus.

In a 1959 essay, he expressed outrage that Mademoiselle magazine, after a photo session, had airbrushed out the crucifix that hung from a chain around his neck. “I am a Beat,” he wrote, “that is, I believe in beatitude and that God so loved the world that He gave His only-begotten Son to it.”

Ginsberg seemed to thrive on fame. Kerouac, an extreme introvert, found it difficult. Already a heavy drinker, he now could not begin a public reading or television interview unless he was very drunk.

He tried on several occasions (recorded in his novels) to find relief in solitude. In 1960, he took a working vacation at Ferlinghetti’s remote cabin, but there he suffered a sudden, insane terror, believing that his companions were plotting to poison him.

Then, according to his account, he had a vision of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the cross of Jesus Christ and numerous angels. He said, “I’m with you, Jesus, for always. Thank you.” And so it was that he renounced Buddhism and, in intention at least, took up the Faith of his childhood.

Gradually, too, he renounced other associations, including the Beat label. In his novel “Lonesome Traveler” (1960), he wrote: “I’m actually not a Beat but a strange solitary crazy Catholic mystic.”

In “Satori in Paris” (1966), he says definitively: “I’m not a Buddhist, I’m a Catholic.” Indeed, one “satori” in the book — “satori” is a Japanese Buddhist term for “illumination” — is an impassioned apologia for the Catholic faith.

The Beats — even those who were not Catholic — found a sympathetic reader in the monk Thomas Merton.

Merton’s 1948 memoir, “The Seven Storey Mountain,” had sold spectacularly and had received favorable notice from the literary establishment on both sides of the Atlantic. He achieved the paradoxical status of celebrity-monk, a prolific author somehow bound by a vow of silence.

Like many of the Beats, Merton was an alumnus of Columbia University, and he shared many mutual friends with Kerouac and Ginsberg. He also shared their interest in Eastern religions, though his study was far more disciplined than theirs.

In a 1960 letter, Merton took note of the poetry of Ginsberg: “I think it is great and living poetry and certainly religious in its concern. In fact, who are more concerned with ultimates than the beats? … I am a monk, therefore by definition, as I understand it, the chief friend of beats. …”

Kerouac, Snyder, Ferlinghetti, and others had read Merton’s memoir and cited its influence on their lives. Merton kept up a correspondence with some of the Beats and published their work in his own literary journal, “Monk’s Pond.” They, in turn, included him in some of their anthologies. Kerouac was an admirer of Merton. They met once, but Kerouac was too drunk to sustain a conversation.

From the late 1950s onward, Kerouac regularly contributed stories and poems to Catholic periodicals, refusing payment for his work. Even Allen Ginsberg was known to give free poetry readings at Catholic Worker houses, and he corresponded with the Servant of God Dorothy Day.

As the 1950s wore into the 1960s, many of the Beats found their place as high priests in the new hippie counterculture. Ginsberg became a guru of sexual liberation and hallucinogenic drug use.

Kerouac became more withdrawn. He spent increasingly less time on the road, and he moved back in with his mother. Though he resisted any return to the practice of the Faith, he became increasingly more strident in expressing his Christian identity.

When a prominent literary critic derided him as a “square,” he replied, “If he means because I’m a French Canadian Catholic … sometimes devout … then I guess that makes me a square.”

An interviewer in 1963 asked Kerouac if the Catholicism in the novel “Visions of Gerard” represented “something new” for him. Kerouac responded, somewhat testily, that all his novels had been Catholic, and he walks through them one by one. “I’m born a Catholic,” he said, “and it’s nothing new with me … I always carry my rosary.”

In 1964 he complained about his cohort: “These beatnik poets have been insulting Jesus and the Virgin Mary right and left for the last six years in poems, including Ferlinghetti and all those guys!”

If anyone said anything critical about Jesus in Kerouac’s presence, he would reply, “Ah, he died for bums like you.”

The walls of the home of his mother, Gabrielle, had already been dominated by Christian images. Kerouac filled up remaining space with his own oil paintings, including crosses, pietàs, images of the saints, and even a portrait of the pope at the time, St. Pope Paul VI.

Near the place where he worked he tacked up two prayers, one by St. Augustine, the other by St. Teresa of Ávila. He confessed to a friend that he liked to sneak at dusk into the nearby Catholic church to hear the priest and people pray Vespers.

But he continued to consume large quantities of alcohol; and the alcohol consumed him in turn. In 1969, at age 47, he suffered a massive, fatal stomach hemorrhage while watching "The Galloping Gourmet” on TV.

The other Beats held some limelight in the decades that followed, but mostly as an oldies act. Ginsberg, a consummate showman, took up a series of causes that were guaranteed to win him notice in the media.

He protested the Vietnam War. He argued for the decriminalization of drugs. In the years leading up to his death in 1997 he was an ardent promoter of the legalization of pedophilia. He was the most prominent public member of the North American Man-Boy Love Association, and this extremely creepy cause was the subject of his last published essay.

Snyder, who usually maintained some distance from the Beats — and often refused the label — embraced Japanese Buddhism and entered the mainstream of American poetry, winning the Pulitzer and other major prizes.

Ferlinghetti, at 99, is still writing and publishing.

In material terms, the Beat Movement is doing better than ever. More of Kerouac’s books are in print today than appeared, cumulatively, during his lifetime. The books continue to sell to successive generations of restless young people, who dream about abandoning the world for footloose travel. In 2002, the manuscript of “On the Road” sold at auction for $2.2 million.

The spiritual legacy of the Beats is messier, though Catholicism has left its indelible mark.

Last year appeared an excellent anthology, “Hard to Be a Saint in the City: The Spiritual Vision of the Beats.” The editor, Robert Inchausti, is professor emeritus of English at California State Polytechnic University in San Obispo.

Inchausti told Angelus News that, after studying the Beats for decades, he has concluded that the “links between the Beats and Catholicism run deep.”

“I think the Catholic elements are essential,” he added. “Kerouac’s incarnational, sacramental, world-inclusive faith came out of his Catholic upbringing and led to his definition of ‘Beat’ as ‘Beatific.’ ”

The Beats, according to Inchausti, were unique among American literary movements for their foregrounding of Catholicism. But he acknowledged that the lives of the authors failed to live up to their sometime religious influences.

Still, he sees the spirit of the Beats alive in some Catholic authors writing today. He singles out Heather King, whose work “strikes me as having much in common with Kerouac’s confessional writing.”

“Unfortunately,” he said, “Kerouac never found the Twelve Steps or lived long enough to write a midlife ‘second conversion’ story. Had he done so, his last books might have been his best. Who knows?”

Mike Aquilina is a contributing editor of Angelus. He is author of many books, including “Yours Is the Church: How Catholicism Shapes Our World.”

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!