Catholics everywhere have had to listen to a drumbeat of major sexual abuse scandals since the beginning of 2018, from Chile to Honduras to the United States, and now the Vatican.

In the U.S., a number of bishops have come under criticism for their responses to the Pennsylvania grand jury report on sexual abuse by Catholic priests in the state and the scandal involving now Archbishop McCarrick.

Some of these responses have struck the faithful as bureaucratic, tone deaf and more concerned with reputation management than with addressing the harm done to victims and to the faith of ordinary Catholics.

Following the “testimony” of the former apostolic nuncio to the United States, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, bishops seemed to split between calls for serious investigation and outright dismissal of the allegations as a politically motivated smear.

More than a few Catholics have started talking about the need for a “Year of Penance” in the Church, like previous years devoted to faith and mercy. Anyone who has spoken to an abuse victim, or read through the more graphic accounts in the grand jury report, can appreciate how much the Church has to be penitent about.

Pope Francis has called on the whole Church to pray and fast in penance for the horrors of the sexual abuse crises afflicting the global Church.

From my perspective as a canon lawyer and lifelong Catholic, what stands out from Church authorities’ handling of sexual abuse cases over the last several decades (whether these cases were admitted, proven and alleged) is a focus on “ends” and an apparent indifference to the ‘“means” used to resolve them.

A desire to “resolve” allegations or proven instances of abuse as quickly and quietly as possible led, inexcusably in my opinion, to priests — or even cardinals — being moved from place to place and to settlements for victims in exchange for their silence.

But even as Church authorities moved in the direction of reform, the emphasis remained on resolving situations by the most expedient means. Some bishops have publicly stood on their records of “zero tolerance” for allegations of sexual abuse. But there are questions about what this means in practice.

Following the publication of the Pennsylvania grand jury report, Cardinal Donald Wuerl has come under perhaps the most sustained public criticism for his handling of abuse cases while he was bishop of Pittsburgh from 1988 to 2006.

Cardinal Wuerl has said that during those years he received accusations against 19 priests, and he immediately removed 18 of them from ministry. But critics ask what does this really mean? Were they all referred to the civil authorities? Were all their cases sent to Rome with a request for laicization, or were the priests sent for psychological counseling and treatment?

Critics among the laity are also asking: How many of those removed from ministry were kept out of parish ministry but assigned a desk job in the diocesan chancery? How many had their faculties revoked and were simply left to disappear into the world with a pension?

What has become clear with this latest round of scandals is that “zero tolerance” can include cover for various ways of getting a priest “out of ministry,” and not all of them are satisfactory.

Following the abuse scandals of the early 2000’s, the U.S. bishops adopted a Charter for the Protection of Young People and a revised set of “essential norms” that promised tough new processes for handling allegations against priests; these were complemented by canonical reforms in Rome.

But it is not as if there was a procedural vacuum before 2002. Both the 1917 and 1983 codes of canon law had clear legal processes for dealing with clerics accused of grave crimes.

It wasn’t that these procedures did not work; it is that few bishops troubled to use them. Even since 2002, there seems to be a desire to skip over due process and arrive at a resolution; the recent case of Archbishop McCarrick is a striking example.

Following the allegations made against him this summer, it was announced that a preliminary investigation had been launched into one of the accusations by the Archdiocese of New York.

Having found that there was at least the minimum appearance of credibility, New York forwarded the case to Rome. Since then, Archbishop McCarrick has had his resignation from the College of Cardinals accepted and been publicly instructed to live in “prayer, penance and seclusion” until the conclusion of a full canonical process.

Now it has emerged, if Archbishop Viganò is proven to be telling the truth, that this may even be a return to sanctions previously and discreetly imposed by now Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI.

These actions ensured that the world understood just how seriously Rome was taking the Archbishop McCarrick allegations. They also effectively imposed a serious, nearly the most serious, canonical penalty on Archbishop McCarrick before the canonical process Rome insisted would follow.

Once again, Church authorities appear to have skipped over the hard work of getting to a credible resolution in favor of banking a seemingly strong response as quickly as possible.

Legal mechanisms aside, there’s something that the numerous protests, widely circulated letters and an outpouring of commentary on social media all point to: that the faithful do not want to be reassured that lessons have already been learned; they want a moment of public reckoning for the sins of the past — they want justice.

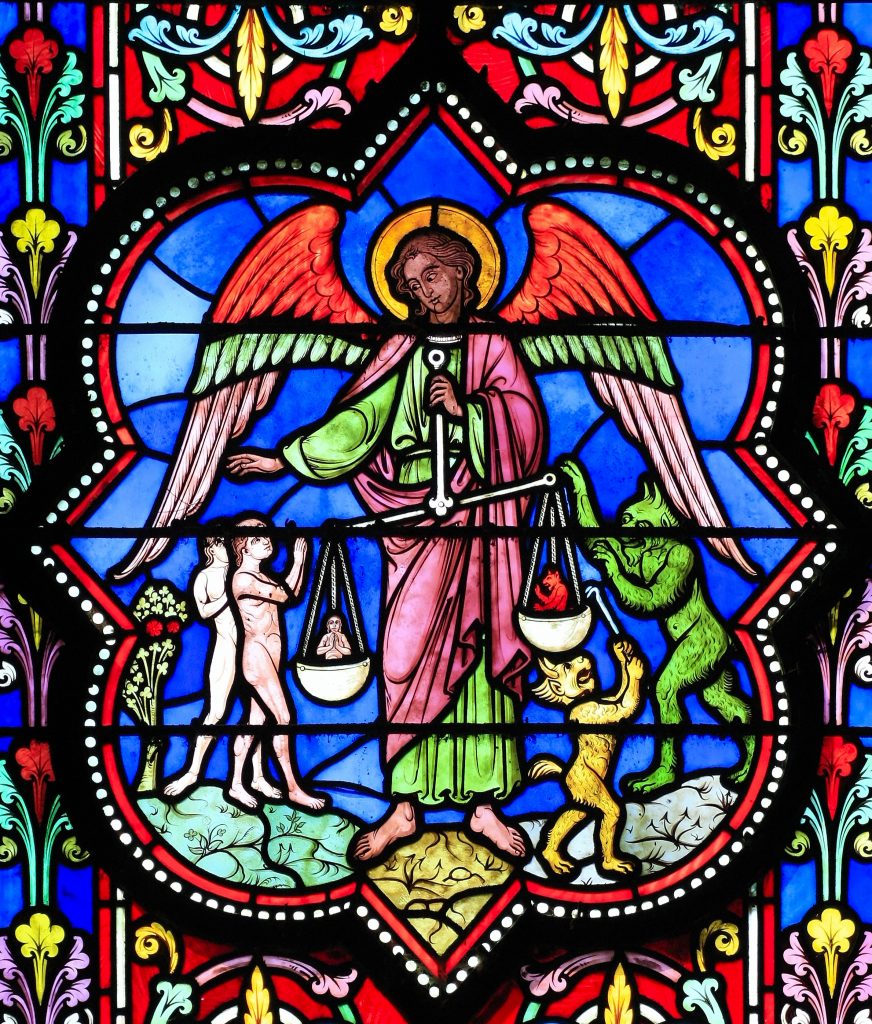

Justice is a tricky word in the Church. Most often it is invoked as the opposite of mercy when, in fact, it is its necessary complement. St. Thomas Aquinas said that mercy without justice was the mother of dissolution, and he was not wrong.

Some of the strongest outrage in recent weeks has been directed at bishops who were seen to be reflexively “merciful” to abuser priests and denied justice to the victims of abuse. In some cases, admitted abusers were returned to ministry after a period of therapeutic “assessment” and “treatment,” only to reoffend.

Untempered by justice, these “merciful” instincts led to the spiraling horrors detailed in the parts of the grand jury report. But similarly, punishment without due process is itself a denial of justice.

It is a denial to the accused, who deserve the chance to be heard and to defend themselves. It is a denial to victims, whose suffering demands that the Church look long and hard at what has happened to them and, for its own sake, articulate with clear and precise legal reasoning what happened, and how it was allowed to happen.

Looking back at the seven decades covered by the Pennsylvania report, what was lacking in all those years was justice. Justice remains the necessary medicine the Church needs. The pope has the power to write the prescription, to administer a time of examination, of honesty and of true accountability.

The Church does indeed need to do penance, but first we need a Year of Justice — and I suspect we shall have it. The question is will the Church give it to herself, or will it be forced on her by more state’s attorneys general.

Ed Condon is the Washington, D.C., editor for Catholic News Agency. He has a doctorate in canon law, which he practiced for a number of years as an independent consultant to dioceses across the United States.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $25! For less than 50 cents a week, get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!