The revelation in late November that a Chinese researcher had edited genes in human embryos and then implanted them in a woman was "a train wreck of a thing to do," said an ethicist at the National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia.

"Normally clinical research proceeds in phases. First, you verify it works in animals, etc. Second, you verify that it's safe. In small things you verify it's effective," said John Brehany, the center's director of institutional relations. "He skipped all that stuff."

"He says, 'I practiced in animals and human embryos.' Even the Chinese officials are saying he violated their standards," Brehany told Catholic News Service in a Nov. 30 telephone interview from Philadelphia. "He said he didn't want to be first, he wanted to set an example, but he's toying with human health. He said he practiced on human embryos, so that means he probably destroyed them. He practiced in the context of experimentation."

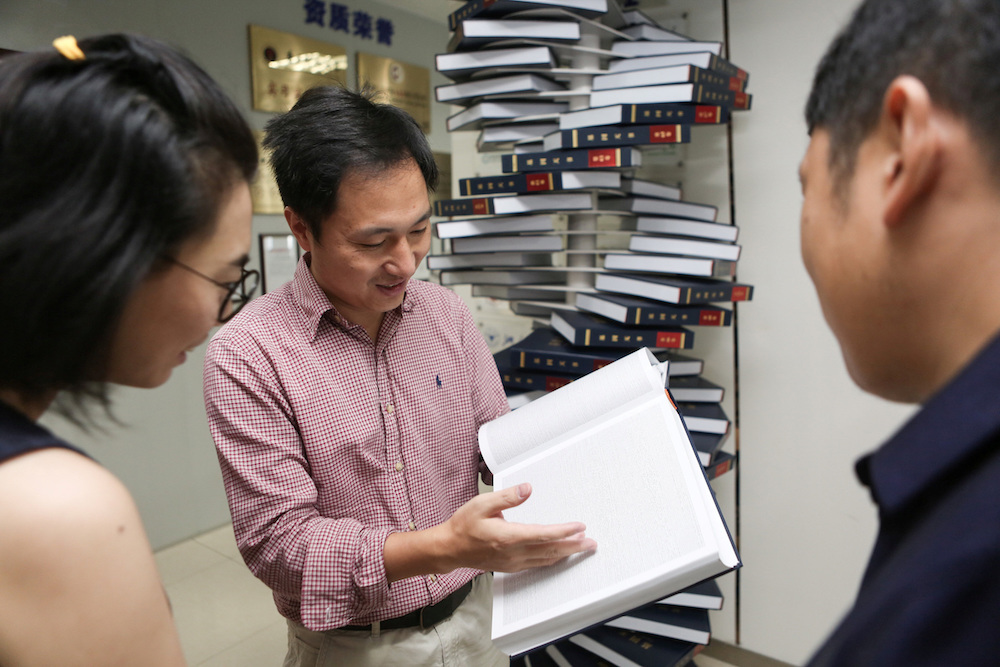

Brehany was referring to He (pronounced "hay") Jiankui, who first revealed his efforts Nov. 26 during an international gene-editing conference in Hong Kong. He learned the gene-editing technique known as CRISPR while doing advanced research at Rice University in Texas. His partner from Rice may face sanctions from the U.S.-based National Institutes of Health depending on the depth of his involvement in the scheme.

"CRISPR" stands for "clusters of regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats." This is a specialized region of DNA having two distinct characteristics: the presence of nucleotide repeats and spacers.

Newsweek reported Dec. 3 that He has not been seen since participating at the International Summit on Human Genome Editing and may be under house arrest by Chinese authorities.

"The couples were offered free fertility treatment if they participated in this, and that's an unethical inducement," Brehany told CNS. "They might have been told it was a vaccine for AIDS," as the babies' father was HIV-positive, he added; He had said he sought to remove the gene that triggers HIV infection. "In other words, there are multiple, multiple ways this was a hash. It really was a hash."

Gene editing is nothing new, Brehany said. "There's a lot of gene editing that goes on in agriculture and in animals and there have bene some experiments and attempts that have gone on in humans, very carefully done, that have gone on since the 1990s," he added. "A lot of this has not been successful, in part because the human immune system tends to think that new genes that are introduced are foreign bodies."

Tomatoes and animals are one thing. Humans, though, are another.

"There have been a number of attempts at gene editing for things like cystic fibrosis, sickle-cell anemia, a number of conditions that shorten people's life," Brehany said. "When you are introducing changes into somebody's body, they don't go any further. Either they don't go any further, or they die.

"If you introduce changes into a woman's eggs, or a man's sperm, or a human embryo within a very short period after conception, then those genes not only introduce genes into cells but into future generations, and that is both an opportunity in some respects, but it's also controversial for a couple of reasons. He set out to do just that. And again ... in a couple of countries they've approved this for a few things," Brehany said.

One country where some human gene editing is legal is the United Kingdom. It is illegal in the United States, and after the furor erupted at the Hong Kong conference, China said what He had done was illegal in China.

The Catholic Church's position is spelled out in the 2008 Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith document "Instruction 'Dignitas Personae' ('The Dignity of a Person'): On Certain Bioethical Questions." The dignity of a person, the document says, "must be recognized in every human being from conception to natural death. This fundamental principle expresses a great 'yes' to human life and must be at the center of ethical reflection on biomedical research."

Other faults Brehany found with He's work included: practicing gene editing on other human embryos first; implanting twin embryos even though one of the twins did not carry the new trait, and may be "a patchwork of cells with various changes"; giving notice of his research only after he started; and having no experience running human research trials.

"On a normal day, in vitro fertilization already separates procreation from conjugal love," Brehany said. "It also introduces the option, and the temptation, of eugenics -- checking out embryos by sight or sophisticated analysis to learn which exhibit optimal health or traits. Those that don't measure up are routinely discarded."