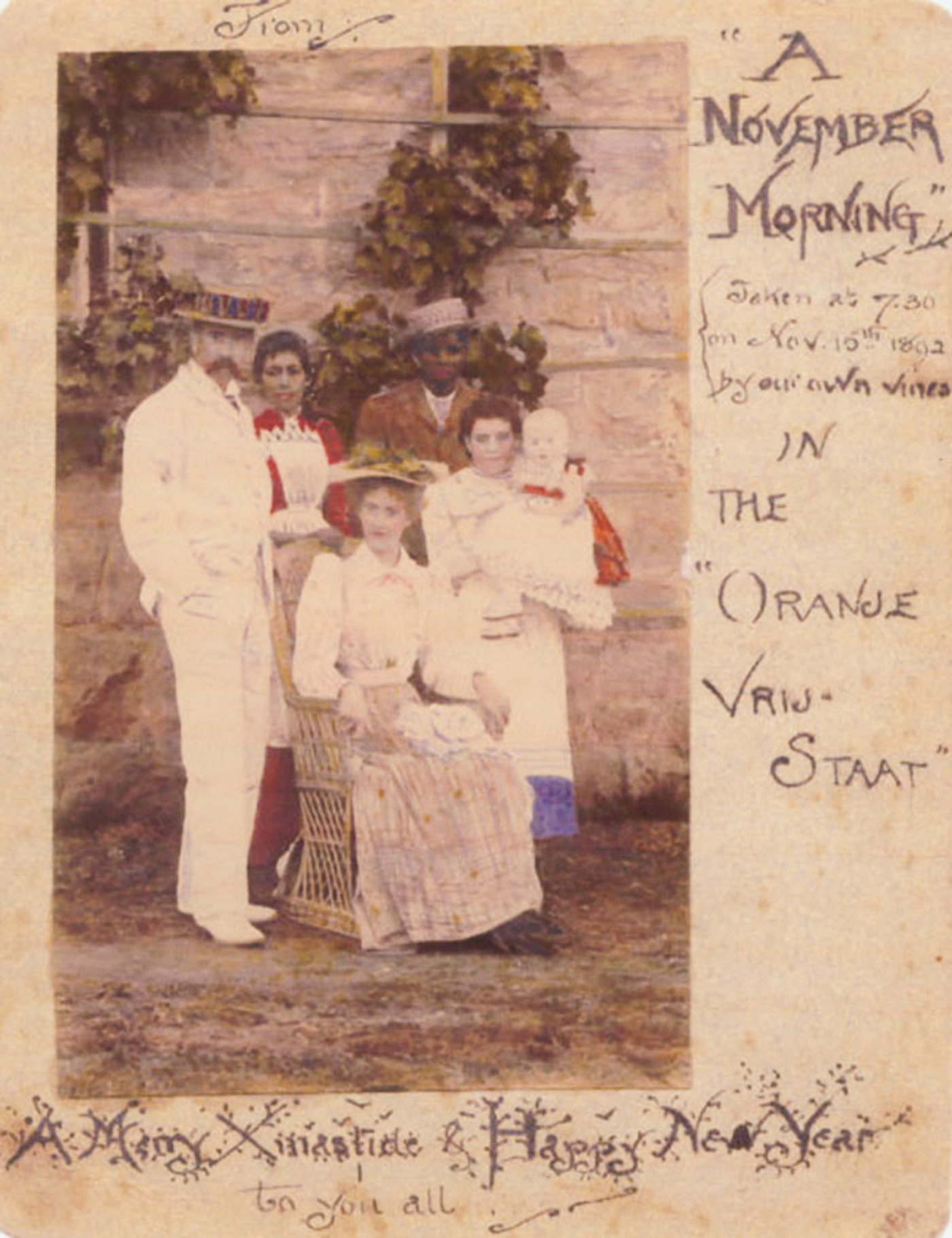

On April 16, 1891, in the Anglican Cathedral of Cape Town, a young couple exchanges vows. The bride is only 21 years old, and has arrived in South Africa only a few days before after a long journey on the sea. It is the end of a long wait for her. Her history with her beloved Arthur Tolkien, a man 13 years her senior, has not been trouble-free.

There were objections from her family, not to mention the thousands of miles that separate the city of Birmingham, in the English Midlands, from the exotic country where Arthur had recently immigrated to, with the hope of a better job. But the wait was over, and for Mabel Suffield life now blossomed with the promise of happiness and love in a new land under an everlasting sun.

It was not to last. Arthur’s job was demanding, and the South African climate and lifestyle proved almost unbearable to her — and especially to her first son, born in Bloemfontein the following year.

In April 1895, Mabel traveled back to England for what should have been a short vacation with her two small children. But her husband was not to join them, having died unexpectedly in South Africa a few months later, leaving Mabel a young widow, with little income and an uncertain future.

We don’t know exactly what happened in the heart of Mabel in the following years, but we know that in June 1900 she was accepted into the Catholic Church after a path of conversion that began with the death of her husband.

It was a conversion that proved fatal. The anti-Catholic sentiment of the Suffields and Tolkiens was strong, and Mabel died four years later, forsaken and exhausted, after “killing herself with labour and trouble to ensure [her children] keeping the faith,” as her son would write many years later.

Today, Mabel is buried in the cemetery of Rednal, on the outskirts of Birmingham, not far from the grave of the soon-to-be-saint Cardinal John Newman. His charism nurtured her in her final years, and would later nourish her own sons, whom Mabel entrusted, to the families’ wrath, to one of Newman’s pupils, the Catholic priest Father Francis Morgan.

J.R.R. Tolkien never doubted that his mother was a martyr, and that his own faith had been bought at the cost of her sacrifice. The sacrifice was a worthwhile one, and the seed implanted into her firstborn would richly blossom, in God’s time, and eventually produce what is undoubtedly the most widespread and influential Catholic work of the modern world.

Handwritten Christmas card with a color photo of the Tolkien family, sent by Mabel Tolkien from the Orange Free State to her relatives in Birmingham England, on Nov. 15, 1892. (WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

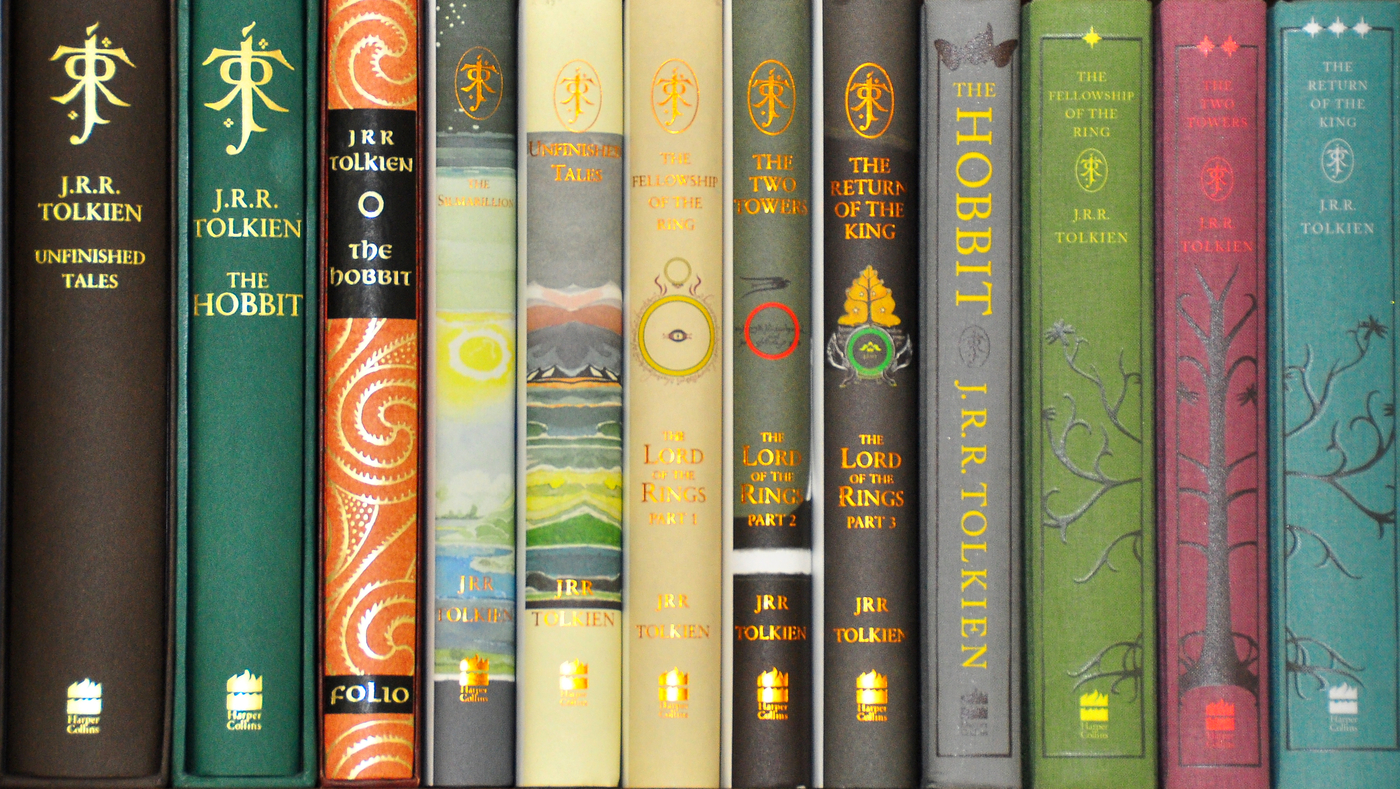

The “Catholicism” of Tolkien’s work cannot be denied. Tolkien himself described “The Lord of the Rings” as a “fundamentally religious and Catholic work.” But what does this mean?

The book can be called Catholic not just because its author remained a committed Catholic throughout his life, honoring the memory of his mother with a heroic devotion to the sacraments and a staunch love and loyalty to the Church.

Any reader of his letters cannot help but admire the strength and simplicity of Tolkien’s faith, often shining in daily family life or communional contexts, such as that with his school friends, the members of the Tea Club and Barrovian Society (T.C.B.S.).

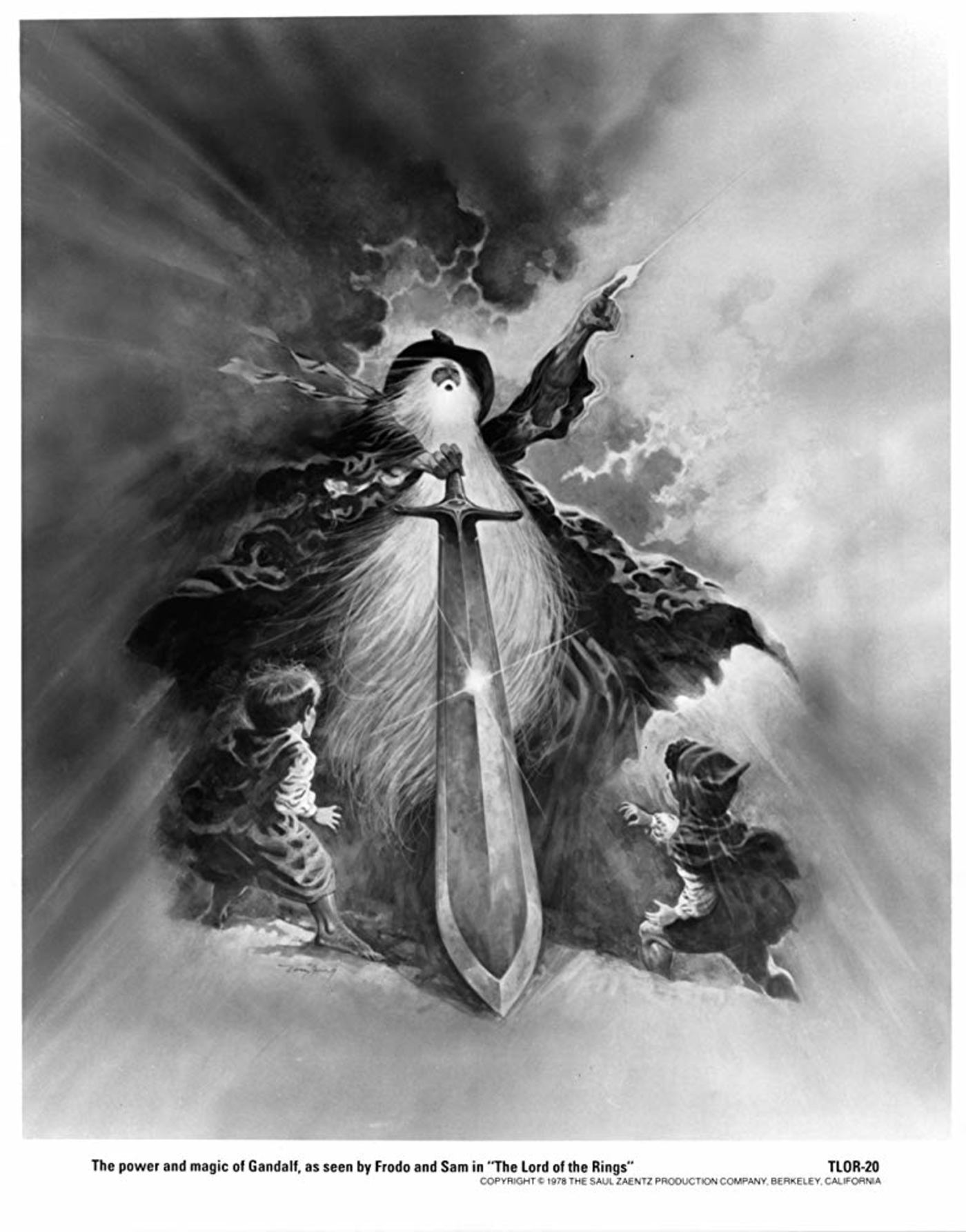

“The Lord of the Rings” is not a Catholic work only because some elements it contains can be associated with key aspects of Catholic devotion, such as the Christ-type figure of characters like Gandalf, Sam, Frodo and Aragorn, the eucharistic symbolism of the Elvish “lembas” bread, the chronological parallels between the novel’s timeframe and the liturgical year, the Marian characterization of Galadriel, and so on.

Nor does the Catholicism of Tolkien’s work depend solely on the range of supposedly Catholic “values” or “concepts,” which can be distilled from the novel — from friendship to self-sacrifice, from the power of mercy to ecology, to name just a few.

Tolkien’s books certainly do figuratively represent elements of Christian truth. He himself claimed “to have as one object the elucidation of truth, and the encouragement of good morals in this real world.”

Among these “elements of truth,” one should highlight in particular Tolkien’s vision of world history as the clash between two narratives: a human narrative, more visible to the eye and consisting in a long, inexorable defeat under the power of death and decay; and the growing narrative of God, more hidden and secret, carried through by humblest characters, and yet ultimately leading to victory.

Perhaps Tolkien summed it up best in two letters to his son, written during a time under the darkest shadows of the 20th century:

“What is really important is always hidden from contemporaries, and the seeds of what is to be are quietly germinating in the dark in some forgotten corner, while everyone is looking at Stalin or Hitler. No man can estimate what is really happening at the present sub specie aeternitatis. (…) One knows that there is always good: much more hidden, much less clearly discerned, seldom breaking out into recognizable, visible, beauties of word or deed or face — not even when in fact sanctity, far greater than the visible advertised wickedness, is really there.”

This vision, of course, is a deeply Christian one, and can be related to Tolkien’s outlook of his own mother’s story. It is also central in the narrative of the book, where victory is achieved, against all hopes, thanks to the heroism of humble Hobbits, and of a hidden king, described as a “deep root” that is “not reached by the frost.”

Finally, Tolkien’s work is not “Catholic,” in the etymological sense, only because of its accessibility and universality, although these were both wished for. With the novel’s pre-Christian setting, Tolkien indeed also aspired to touch the audience of his contemporary, post-Christian society.

This aspiration was fulfilled, and millions of readers from all backgrounds have been enthralled by and enjoyed the book, experiencing a reawakening of what could be called “religious sense”: the same “desire for the High” (and ultimately of God) that Gandalf reawakens in the Hobbits.

While all the above is true, “The Lord of the Rings” (and the rest of Tolkien’s literature in general) is Catholic not just, and perhaps not really, because of that.

Image from the 1978 film “The Lord of the Rings.” (IMDB)

What is truly and above all Catholic in “The Lord of the Rings” is rather how it came about, the road, or “method,” which Tolkien followed to write it, the mental framework in which it sprung and developed. The book indeed emerged not as the fulfillment of the author’s pre-existing plan, as the product of an intellectual endeavor or of an apologetic, didactic, or cultural strategy.

Rather the book “happened” in Tolkien’s life, as the unexpected fruit of someone else’s will, to which he merely offered his own availability, following a vocation that he recognized, rather than devised.

This can be illustrated, following Tolkien’s practice, with a short story from his life, in which Tolkien reports his fortuitous encounter with an eccentric old fellow:

“Suddenly he said ‘Of course you don’t suppose, do you, that you wrote all that book yourself?’ Pure Gandalf! I was too well acquainted with Gandalf to expose myself rashly, or to ask what he meant. I think I said: ‘No, I don’t suppose so any longer’. An alarming conclusion (…) but not one that should puff anyone up who considers the imperfections of ‘chosen instruments’ and indeed what sometimes seems their lamentable unfitness for the purpose.”

Gandalf is for Tolkien a divine entity, the symbol of divine grace: in the anecdote it is thus God himself, divine “Truth,” who claims “co-authority” of Tolkien’s stories and reminds him of his purely instrumental role.

Tolkien often described himself as an instrument of God, and wished to be such from his early years. As he wrote to his school friends of the T.C.B.S. club, “The greatness I meant was that of a great instrument in God’s hands — a mover, a doer, even an achiever of great things, a beginner at the very least of large things.”

This self-awareness of being called to be an instrument in God’s hands, and not primarily a defender of doctrines or values associated with him, is visible at all stages of the composition of “The Lord of the Rings.”

For instance, Tolkien often recalled that while writing the book, he “was not inventing but reporting (imperfectly) and had at times to wait till ‘what really happened’ came through.”

Tolkien saw his writing as an “event,” of which he only presented an imperfect “report.”

If, for example, “The Lord of the Rings” shines with the beauty of Christian truth, this does not come from Tolkien’s mind, but is rather mediated by it — much like the Virgin Mary’s role in the conception of Jesus.

Tolkien did realize from his young age that he was destined “to kindle a new light, or, what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world” that is “to testify for God and Truth.” And yet he never believed that the light of God’s truth, which can be glimpsed in his books, came from himself, but rather it was “refracted” through him — to use a recurrent image used in his works.

The beauty and truth of “The Lord of the Rings” are thus rooted in Tolkien’s faith, which yet is not a repository of themes and values, but rather the source of an attitude to life’s circumstances, seen as the place where God brings about his narrative, a plan that calls for human cooperation.

Tolkien’s Catholic attitude toward the “mystery of literary creation” was simply a reflection of his general attitude to the circumstances he was called to live, which, in his own words, he considered as God’s “instruments or His appearances.”

This was Tolkien’s simple faith: simple but as great as that of his mother, the same simple and yet powerful faith of millions of ordinary Catholics.

Detail of J.R.R. Tolkien’s book collection. (SHUTTERSTOCK)

If one goes even deeper, one should conclude that “The Lord of the Rings” is ultimately rooted in the faith of Tolkien’s mother, the young Mabel Tolkien, who died as a hidden witness, or martyr, of the story that took hold of her during her short, dramatic life. As Tolkien himself recognized, reacting to the first wave of enthusiasm for his “The Lord of the Rings”:

“As a matter of fact, I have consciously planned very little; and should chiefly be grateful for having been brought up (since I was eight) in a Faith that has nourished me and taught me all the little that I know; and that I owe to my mother, who clung to her conversion and died young, largely through the hardships of poverty resulting from it.”

In this sense, Tolkien’s most famous work is a deeply Catholic one. “The Lord of the Rings” serves as a witness of the truth and beauty that our imperfect, wounded life can produce, for the good of a wounded world, when one adheres to the vocation that he or she is called to live, in the intimacy of one’s relationship with God and the loyalty to the Church and its sacraments.

It illustrates the truth that one’s task is not necessarily to “achieve great things,” but rather to plant a seed under the frost, which God, in his own time, will bring to blossom.