The early decades of what we call “Hollywood” were not innocent ones. When film became a popular form of mass entertainment, the violence and sexuality of early silent features shocked average audiences, giving the industry a reputation as a den of hedonism and lechery. Organized Christian groups like the Catholic Legion of Decency mobilized to rein it in — to some success.

Given the subject matter, “Babylon” (in theaters Dec. 23) is an inspired title for director Damien Chazelle’s newest work, an epic post-modern dramatization of the decade-long transition in Hollywood from silent films to sound films. It borrows heavily in ideas and allusion to the classic 1950s comedy musical “Singing in the Rain” with the intention of revealing darker truths than its progenitor. Like its namesake city, it is a movie about a decadent, evil place that spreads chaos and corruption … Hollywood.

Chazelle’s films — “Grand Piano,” “Whiplash,” and “La La Land” among them — are stories about dreamers who accomplish miraculous feats, singularly minded men and women with the talent to play an impossible song on the drums or land a spacecraft on the moon.

“Babylon” might be his most ambitious and indulgent exploration of these ideas yet. We meet a large cast of eccentric, talented cutthroat artists at the height of the silent film era. Off the job, meanwhile, their lives are depicted in montages of hedonistic orgies, drug-fueled mania, and high stakes gambling. They are unable to hold down marriages, find authentic relationships, or live without expensive and costly vices — and the film portrays their condemnation quite graphically.

This hedonism is romanticized by the characters who look back on it fondly as a reflection of the height of their creativity and success. In triumphalistic tones, the film seems to celebrate the fact that the sex and violence Christians once protested against is now mainstream and appealing.

But like its progenitor “Singing in the Rain,” this all comes crashing down as Hollywood embraces sound technology, and actors who were beloved in the 1920s can’t adapt to the new paradigm of the 1930s. With characters this toxic, it isn’t surprising to watch them melt down and collapse under the weight of their vices.

But like most films about filmmaking, this one struggles to reckon with the consequences of Hollywood culture. “Babylon’s” most powerful scenes are the ones that contrast the chaotic inner lives of these men and women with the momentous success of their art, seeing how priceless and beautiful moments of art are created and impact future generations.

Indeed, many of the greatest works of art in history, even religious ones, were made by unhappy, unstable, and even cruel people whose lives were overtaken by the greatness of the art they produced.

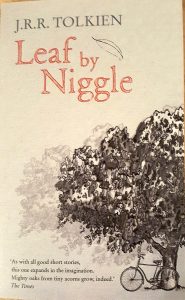

The contrast calls to mind J.R.R. Tolkien’s semi-autobiographical short story “Leaf By Niggle,” which tells the story of an obsessive artist’s struggle to paint a perfect tree with total detail and success but who never fully succeeds in his life. At the end of the story, he sees a vision of the tree in all of the vision he wished to create. His personal struggle to realize something beautiful and true was found in his effort, not in his worldly accomplishments. Niggle’s spirit was willing but his flesh was weak.

“He went on looking at the Tree,” Tolkien writes of his protagonist. “All the leaves he had ever laboured at were there, as he had imagined them rather than as he had made them; and there were others that had only budded in his mind, and many that might have budded, if only he had had time.”

Unlike “Leaf by Niggle,” though, “Babylon” is populated by indulgent and feckless characters with no answer to the stress of change and the sting of failure. Niggle is easily distracted, lazy, and over-encumbered with life’s challenges.The movie’s characters are laboring to create their own personal hell on earth. The film can’t transcend this and ends up underdeveloped, merely alluding to the hope that art as an end to itself is worth the pain and suffering that goes into it, even as its artists become dead and forgotten. Even then, these characters are mostly consumed by despair and don’t get to see the fruit of their labors as Niggle does when he sees the completed tree.

“Babylon” at its best captures the hope of eternity and the beauty of our suffering in the efforts to improve the world and bring joy to people’s lives. But at its worst, it is a work of self-gratifying indulgence that romanticizes humanity’s worst impulses. Angry, bloated, and self-important but filled with moments of beauty, “Babylon” can’t escape the hell it recognizes surrounds it.

Chazelle’s Hollywood is far from heaven. It is depicted as a literal hell of sadomasochism and death, drenched in red light and descent imagery. As a result, “Babylon” amounts to little more than a prayer that Hollywood’s very real evils are worth it in the end.