May 2, 2019, will mark the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, painter, polymath, and Renaissance man extraordinaire. Worldwide tributes are underway, including some remarkable exhibitions.

Experts and amateurs are lining up to pay homage to this outstanding Renaissance personality, extolling his pioneering interest in science and engineering, his exceptional drawing and painting skills, his love of nature, and (of course) his presumed sexual orientation.

Dan Brown’s novel “The Da Vinci Code” will enjoy another spike in sales, and Walter Isaacson’s tendentious and tedious tome of a biography will be the go-to reading for many a flight to Milan, Paris, and London, as devotees celebrate one of the greatest creative minds Christendom ever produced.

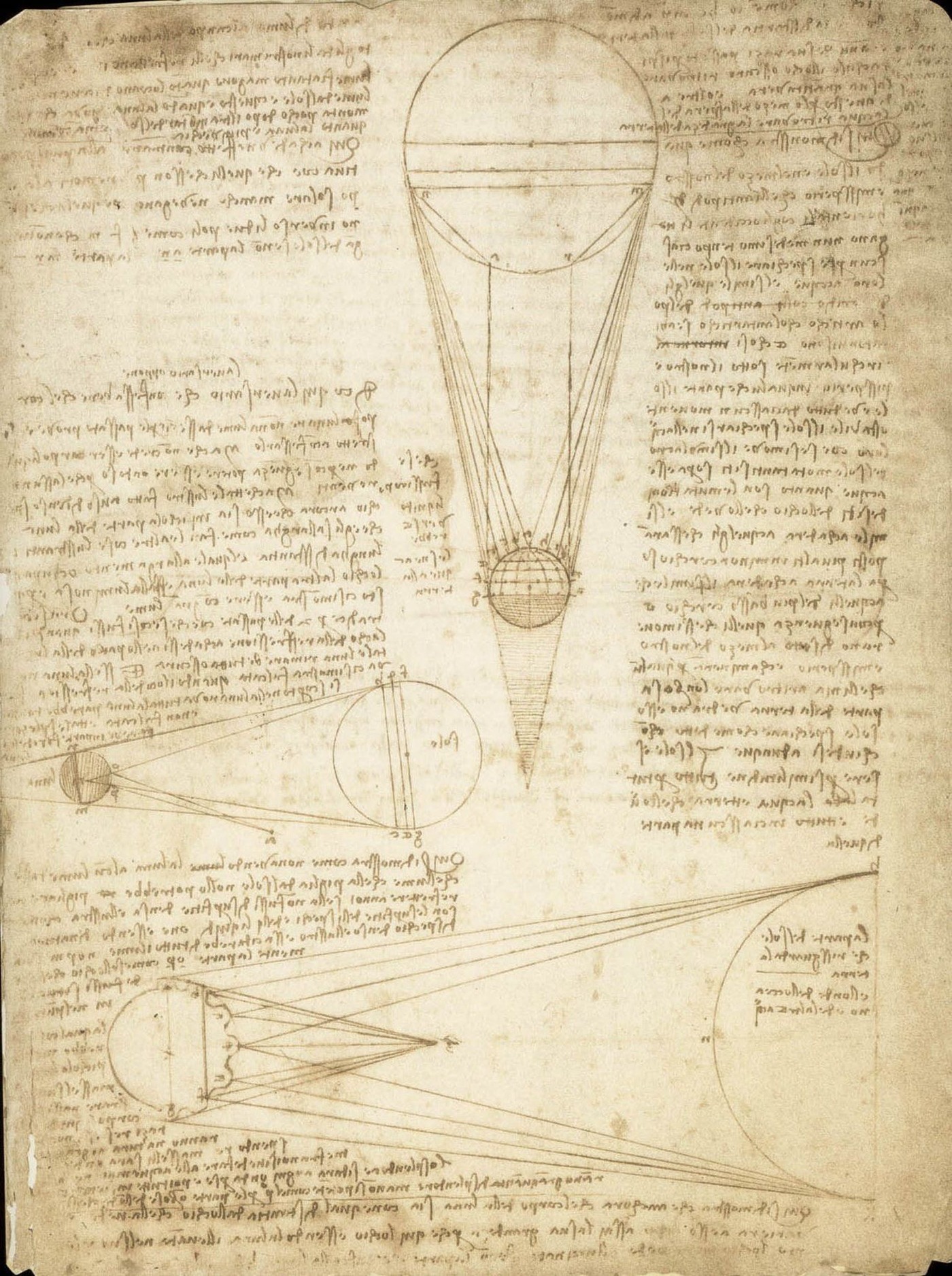

Florence, Leonardo’s hometown, got a head start on the festivities with an exhibition of the “Codex Leicester” at the Uffizi Gallery, ending on Jan. 20, 2019. This notebook, compiled between 1507 and 1508 in Florence, was purchased by Microsoft founder Bill Gates in 1994 for more than $30 million dollars.

Visitors have gazed upon these pages while a few steps away from his early paintings of the “Baptism of Christ,” “The Annunciation,” and the unfinished “Adoration of the Magi.”

Milan, Leonardo’s home from 1482 to 1499, is transforming into a Da Vinci trail. The Castello Sforzesco, where the Florentine painter worked in the court of Ludovico the Moor, will unveil the five-year-long restoration of Leonardo’s lovely and mysterious “Sala delle Asse” on May 2 of this year.

The Ambrosian Library, built by Cardinal Federico Borromeo, will feature two of its treasures: Leonardo’s “Portrait of a Musician” and the “Codex Atlanticus,” another of the artist’s notebooks. And naturally, Leonardo’s gift to mural painting, “The Last Supper,” will be even more in demand, so best book tickets for your 15-minute time slot now.

The “Codex Leicester” is a world-famous manuscript, which contains groundbreaking thoughts and notes by Leonardo da Vinci. (LE GALLERIE DEGLI UFFIZI)

The European tour of the “Codex Leicester” will continue in London, where the British Library will host an extraordinary exhibit titled “Leonardo da Vinci: A Mind in Motion” from June 7 to Sept. 8, 2019. For the first time, the British Library’s “Codex Arundel,” the “Codex Forster” from the Victoria and Albert Museum and the “Codex Leicester” will be displayed together.

A side trip to Rome would be rewarded with the Leonardo exhibition at the Quirinale Stables from March 11 to June 30, 2019, along with the several museums already in place to celebrate the artist who lived in the Eternal City between 1513 and 1516.

Even the Vatican Museums have an unsung treasure by the artist — the unfinished “St. Jerome,” evocative and instructive as Leonardo’s works always are.

Don’t expect much painting in the Rome exhibitions — the blockbuster Leonardo painting show is awaited at the Louvre, owner of the greatest number of his extant panels.

The exhibit will feature “Mona Lisa,” “Virgin of the Rocks,” “St. Anne and the Virgin,” “La Belle Ferronnière” and “John the Baptist,” along with spectacular loans, including the “Salvator Mundi,” which broke all sales records in 2017 when it sold for $450 million at Christie’s.

The work has not been seen since its sale, so the first unveiling will be a major event. Mercifully, the show will take place during the slow season for travel, so for those of you who can get away between Oct. 24, 2019 and Feb. 24, 2020, I suspect it will be worth the trip.

In this way, the modern era will laud the worldliness of Leonardo who, in its mind, achieved his greatness by mastering things of this world and implicitly by rejecting all things divine. This, however, only presents half of his complex picture.

Leonardo’s restless and curious mind was indeed fascinated by engineering and problem-solving. He loved to speculate, pushing the boundaries of nature whether in flight, the complexities of the human anatomy, or mechanical engineering, but he was also stimulated by wrestling with complex questions of faith.

Leonardo was not famous in his day for his notebooks or his inventions but for his religious works, which were astonishingly avant-garde. These were not the efforts of an artist paying lip service to the cultural mores of his age, but a man exploring complex levels of theology.

His “Adoration of the Magi,” left incomplete when he went to Milan, departed from the typical triangular composition by forming a swirling eddy of bodies around Mary and the Christ Child.

Like a model of a solar system, the faces and bodies orbit around the Light of the World. His magi, prostrate yet magnetically drawn toward Jesus, express man’s yearning to see God.

The following year in Milan, shortly after Pope Sixtus IV instituted the feast of the Immaculate Conception, the confraternity of the same name commissioned Leonardo to produce a panel for their new altar to be inaugurated on Dec. 8, 1483. Known as the “Virgin of the Rocks,” the completely innovative iconography of this work reimagined the Immaculate Conception.

Leonardo, who invented the technique of “sfumato,” creating softer, more subtle painting effects, tackled the thought of the “Subtle Doctor,” Duns Scotus, the Franciscan theologian of the Immaculate Conception.

Scotus argued that Mary’s exemption from original sin was part of God’s plan, which existed before creation had taken place in space and time, so Mary would have been conceived perfect in every way. She would be perfectly holy so as to be a worthy vessel for her all-holy Son.

Leonardo’s mysterious landscape, the swath of golden silk around her womb, and the infant Jesus edging toward the space where the altar would be, were Leonardo’s amazing contributions to Marian theology, but are now forgotten in the modern tsunami of religious ignorance.

“Virgin of the Rocks,” circa 1483. (WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

And the “Last Supper”? How many people have expended time, effort, and money to glimpse this mural for a few short minutes, only to waste them pondering Dan Brown’s trope of a secret marriage between Christ and Mary Magdalene?

Leonardo used every skill at his disposal while working in the refectory of the Dominicans (a religious order that could smell a heresy a mile away, by the way) to capture the exact instant when Jesus announces his imminent betrayal.

His words drop like a stone in still water: Jesus isolated in the center, with the apostles rippling away from him with their varying reactions. The table opens outward, provoking the viewer to identify with one of the men — will it be the traitor Judas? Protesting Peter? Pensive John?

Leonardo’s art brought viewers into the heart of some of the greatest mysteries of faith, but the modern age has turned them into trivial titillations.

The last stop on the Leonardo grand tour is Amboise in the Loire Valley, where the artist died. Invited by King François I, the 64-year-old painter moved into the Château du Clos Lucé with the grand title of “First Painter, Engineer and Architect to the King.”

He spent the last three years of his life comfortably, compiling his notebooks and working on the “Mona Lisa” and “Saint John the Baptist,” which he had brought with him.

He also, according to his biographer Giorgio Vasari, “earnestly resolved to learn about the doctrine of the Catholic faith.” This line, as well as his confession and communion before death, are excluded from Walter Isaacson’s best-selling biography.

Isaacson dismisses out of hand any idea that Leonardo thought about God, referring to Leonardo’s “commending of his soul to the Lord and the Virgin Mary” in his will as mere “literary flourish,” as well as omitting Leonardo’s extensive bequests for Masses to be said for his soul.

Isaacson, desperate to make Leonardo fit his contemporary ideal of a loner, homosexual, and atheist genius, paints a hopelessly anachronistic portrait of the artist and his times.

By contrast, Kenneth Clark, in his shorter yet far better written biography, reflects on Leonardo’s fascination with apocalyptic scenes of the deluge in his old age, and his realization that certain mysteries could not be solved by science.

Carlo Amoretti’s 1804 biography, which was the earliest to make use of archival research, proposed that Leonardo at the end of his life “abdicated things of this world with a grand determination to focus solely on the great themes of death and the afterlife.” It seems that there was a place for God in the heart of this man, after all.

Leonardo’s most dramatic legacy to 2019 is the painting that shocked the world, the half-billion-dollar “Salvator Mundi.” Oddly enough, for a man who is constantly hijacked to promote gay rights or science over religion, Leonardo is the artist who succeeded on putting Jesus’ face front and center in the public square.

Hopefully, Catholics will muster the energy to recapture this genius, and make 2019 not the year of “climate-change Leonardo” or “rainbow Leonardo” or “atheist Leonardo,” but the year of the man who so loved the created world that eventually he came to love its Creator.

Elizabeth Lev is an American-born art historian, teacher, and author who lives and works in Rome.