The record book shows that the 1950 Loyola University football team recorded eight victories against one, two-point defeat, by all accounts the best grid squad in school history.

The same could be said of the University of San Francisco’s 1951 team — nine wins against no defeats and a No. 14 year-end national ranking.

Yet in both cases, these teams’ greatest accomplishments took place not on but off the field — loud and clear statements opposing racism and bigotry, even when it meant losing badly-needed revenue, the lack of which forced both schools to shut down its football programs within two years.

As the 2018 college football season prepares to open this month, amid customary glitz and hype, it is worth looking back nearly seven decades at how two California Catholic universities stood up for principle over monetary gain.

Loyola: ‘The right thing’

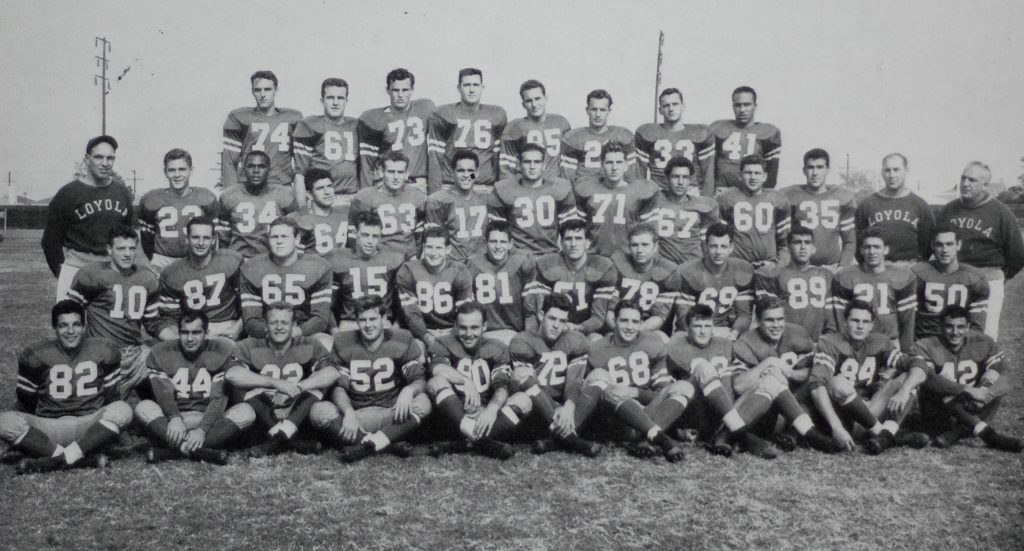

The 1950 Loyola football roster — which included future pros Gene Brito, Skip Giancanelli and Don Klosterman (future general manager of the L.A. Rams) — was the strongest ever assembled on the Westchester campus, which it set about proving by overwhelming Pepperdine 50-14 in its season-opening game Sept. 22.

As Loyola prepared to travel to El Paso, Texas, for its Sept. 30 game against Texas Western (now the University of Texas at El Paso), team manager Red Hopkins wrote to Texas Western officials to verify reservations for the Lions’ traveling party of 52. Hopkins noted that Loyola’s group would include as many as three black players, including star halfback Bill English, plus black trainer, Oscar Cunningham.

Mindful of segregationist policies and attitudes at southern institutions, Hopkins inquired, “What is your policy on this matter?”

Texas Western officials told Hopkins that the “colored” members could stay at the home of the housekeeper of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in El Paso. But that “solution” was rendered moot when the University of Texas’ board of regents — which governed Texas Western — decided to enforce a longstanding rule that blacks could not play for or against university football teams.

Informed of this policy, Hopkins wrote back: “Please cancel our reservations this weekend. Thanks.”

On Sept. 28, Jesuit Father Charles Casassa, president of Loyola, released an official statement declaring, “The decision was regretfully reached because of certain player restrictions which would have been in force were the game to be played.”

In a 2010 LMU Magazine article on the event, Chuck Hovorka, a 1949 Loyola grad and close friend of Father Casassa, noted that the university president “was very firm. He said, ‘I know in my mind I did the right thing as a priest and the right thing if I hadn’t been a priest.’”

Loyola’s decision met with solid public support at home, despite an estimated financial loss of between $5,000 and $10,000, a loss which helped expedite the end of Loyola’s football program by 1952.

If anything, players later said, it brought the team closer together, and the Lions — led by head coach Jordan Olivar, later a coach at Yale — came on even stronger in the season’s ensuing eight games.

They trounced St. Mary’s 48-0, edged San Jose State 14-7, rallied to topple College of the Pacific 35-33, and coasted past Nevada 34-7.

On Nov. 4, Loyola again rallied to beat Hardin-Simmons 21-20, blanked Fresno State 28-0, and then suffered its only loss, a 28-26 heartbreaker to Santa Clara, which ended that year 3-7 but had won the Orange Bowl 10 months earlier.

The Lions ended their season Dec 2 by rallying from a 28-13 deficit to run past the University of San Francisco 40-28.

USF: ‘No regrets’

And that USF team? Not a bad squad, either, finishing 7-4.

In fact, the very next season, the Dons — with future NFL Hall-of-Famers Ollie Matson, Gino Marchetti and Bob St. Clair among its top players, and coached by future Notre Dame and Philadelphia Eagles mentor Joe Kuharich — ran the table with a 9-0 record, the last a 20-2 win over Loyola.

On the train from Los Angeles back to San Francisco, the Dons celebrated their season, which they knew would likely include an invitation to the Orange Bowl. And such an invitation was, in fact, awaiting them once they arrived home.

But there was a problem: The Orange Bowl didn’t want USF’s black players, Matson and co-captain Burl Toler (later to become the NFL’s first black official), to play. (It was speculated, though not proven, that the committees of several major bowl games held in the South had a “gentleman’s agreement” to exclude black players.)

When Kuharich told his team of the Orange Bowl’s conditions, it took but a few minutes for the team to decide.

“We told them to go to hell," said Bill Henneberry, the Dons' backup quarterback, in a 2015 article published on nfl.com. "If Ollie and Burl didn't go, none of us were going. We walked out, and that was the end of it."

The decision cost the school $50,000, a death blow for the football program which was running $70,000 in the red annually. The USF board of regents — despite the team’s success — voted to drop football after the 1951 season.

"But,” Henneberry said, “I never remember hearing anybody say they had any regrets about what we did.”

Epilogue: What goes around...

USF tried to resurrect its football program in the mid-1960s, but financial pressures again forced its closure after only six seasons.

Loyola (which became Loyola Marymount) began a “club football” program, joining an association of more than 100 teams (many affiliated with colleges and universities), and in fact won the club football association’s national title in 1969. Again, however, money issues soon necessitated its shut-down.

And Texas Western, the school that Loyola refiused to play because of its discriminatory racial policies?

The school’s athletic program eventually integrated. By 1966, in fact, the Miners were one of the nation’s top basketball teams, reaching the championship game of the NCAA Tournament at College Park, Maryland, against No. 1 Kentucky — the first ever matchup between all-black (Texas Western) and all-white (Kentucky) starting fives.

The result: a 72-65 win for Texas Western, which had endured questionable officiating in its games during the year, and whose NCAA championship — the only one not captured by UCLA from 1964 to 1973 — was not exactly greeted with enthusiasm by some.

No one brought out a stepladder for the customary post-game cutting of the nets (the team captain had to sit on the shoulders of a teammate to do so). Nor was the team invited to visit the White House (whose occupant, Lyndon Johnson, had signed the historic Civil Rights Act in 1964), or to appear on the immensely popular “Ed Sullivan Show,” as other athletic champions of the day were.

But Pat Riley, a member of Kentucky’s starting five (and later a Los Angeles Lakers’ coach of some renown), came into the Miners’ locker room immediately after the game to congratulate them. He was the only Wildcat to do so.

And the Miners’ athletic success poked the first crack in the dam of southern discrimination. In 1967, schools of the Southeastern Conference began integrating its teams, starting with Perry Wallace playing basketball for Vanderbilt (which later retired his number and established a scholarship in his name).

“One of the reasons we’re still talking about it is something Pat Riley said one time,” Dave Lattin, a star on the Texas Western team, told CBS Sports.com. “He said it was probably the worst day of his life when he lost that game, but he felt the right team won because it did so much for others. It made it possible for kids to go to major universities, especially in the deep South, and not just for basketball. It’s my legacy. When you do something for someone else, it’s a legacy that lasts forever.”

Start your day with Always Forward, our award-winning e-newsletter. Get this smart, handpicked selection of the day’s top news, analysis and opinion, delivered to your inbox. Sign up absolutely free today!