As the shrouds were removed from the five panels of a stunning new tapestry honoring the Blessed Virgin Mary in the apse of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels before morning Mass on New Year’s Day, it seemed fitting that their removal required the sound of ripping Velcro.

A necessarily harsh sound to mark a clean break from a harsh year, one that, as Archbishop José H. Gomez acknowledged that morning, may have felt like a bad nightmare for many.

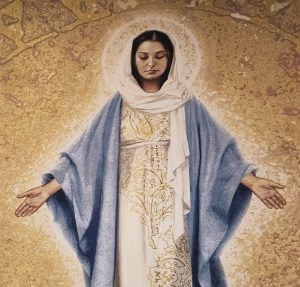

But more importantly, the new tapestry, featuring a 14-foot-high depiction of the cathedral’s namesake, hands outstretched, eyes cast toward the altar and congregation, was unveiled on the day that the Catholic Church celebrates the solemnity of Mary, Mother of God.

And by the time Mass was finished, it seemed as if it had always been there.

For those who have called the cathedral their spiritual home since it was built two decades ago, the 29-by-50-foot tapestry seemed to signal an end, rather than a new beginning.

“That’s always been the whole idea [of the new tapestry],” said Brother Hilarion O’Connor, the cathedral’s operations manager who helped shepherd the project. “The idea being the completion of the cathedral, completion of the tapestries.”

Part of that completion might have felt long overdue. If you’ve walked through the long nave of the cathedral, you’ve likely gazed upon the more than 130 images of saints depicted on tapestries hung on opposite walls.

Perhaps the most well-known of the cathedral’s artistic features, those tapestries were made by Californian painter and tapestry designer John Nava, who used real-life models for his depiction of the “communion of saints.”

But what a visitor did not see until Jan. 1, 2021, was a depiction of the most important saint of them all: Mary, whose many titles in Catholic tradition include “Mother of God” and especially for Angelenos, “Our Lady of the Angels.”

“It was always a little strange that I had [created] 136 figures for the interior of the church, but the one person who was not depicted was Our Lady,” said Nava, who wasn’t the only one to note the odd contradiction of having a cathedral dedicated to Our Lady lacking a prominent image of Our Lady.

Among them was Archbishop Gomez, who, upon arriving in Los Angeles a decade ago, told Brother Hilarion: “You know, we need to get Our Lady into the cathedral.”

And now she has arrived, luminous, in a blue robe that distinguishes her from the saints in the nave, who now seem to look up at her, and that Nava portrayed in muted, mostly earth tones that compliment the cathedral’s natural stone.

This is a young Mary, but one whose countenance contains the unmistakable duality of the mother who is a harbor for our pain, and a woman projecting an air of someone who has experienced pain herself. She is large enough to suggest her power, but still radiates a sense of human vulnerability that so many people connect with.

“She is the archetypal mother, I didn’t want her to be imposing, rather, I wanted her to be open, receptive, sympathetic,” said Nava, who studied art in Florence as a young man and visited many of Europe’s cathedrals, a good deal of them dedicated to Mary. As he did with his “communion of saints” that line the wall, Nava said it was important for this final tapestry to integrate the Church’s ancient tradition and history with contemporary people and times.

“I wanted to connect it to the New World,” he said. “The greatest image of Mary in the new world, I believe, is the Virgin of Guadalupe. That’s why in her robe, I put in that floral pattern from the Virgin of Guadalupe, to refer to that figure.”

The model for Mary was a woman in her 20s that Nava has known most of her life, a DACA recipient who he said was excited to know that her face would be used but who will remain anonymous so as to not confuse matters.

After all, one should be contemplating Mary, not the model, when looking at the tapestry.

“The art history of the Church is so varied, rather than doing a stylized image, I wanted to make a realistic portrait that people could connect with,” said Nava, who took two years to create the tapestry. “Something that they could say, ‘I know someone that looks like that.’ ”

Also recognizable on the tapestry’s two outside panels, left and right, is a street map of downtown Los Angeles that is complete to the point that its upper right-hand corner contains a symbol for Dodger Stadium.

Though he had followed the project from beginning to end, New Year’s Day marked the first time Brother Hilarion had seen the tapestry in its entirety without scaffolding in the way. It is “magnificent in how Our Lady is looking out on the congregation,” he noted, and it represents a fulfillment of what emeritus archbishop Cardinal Roger Mahony declared when it was first built: “I have helped build the cathedral, my successors will complete it.”

Brother O’Connor marveled at how Nava was able to meet the size challenges of the church, the largest Catholic cathedral in the United States, while still maintaining an air of contemplation and scale.

“John has an amazing talent for getting the images to meet the size of the cathedral,” he said. “That’s a big challenge.”

Indeed, with such a project, an artist is tasked with creating something that is visually stimulating without becoming distracting. The art in a church should move us to thought, to prayer, to consideration of our lives, not on how the art got there.

Nava has thought a lot about the role of the artist in such circumstances. When the cathedral first opened, he remembers that his friend, the sculptor who created the statue of Mary at the cathedral entrance, the late Robert Graham, told him, “This isn’t about us.”

Instead, he said, it’s about creating a larger meaning and consciousness for people.

“When you do a show in a gallery, the focus is on you,” he said. “You’re the artist and this is your work. But this is not about John Nava. This is about creating a reality that goes beyond a particular painter.”

And now that it’s done, Nava smirks when asked if he will be creating any more tapestries. He said he is happy that Our Lady has instantly brought a “rightness” to the cathedral. Before it was unveiled, it was not uncommon for congregants to look toward the back of the church, at Nava’s equally magnificent baptism tapestry.

“People used to joke that the church was backwards because everybody looked that way,” Nava said, gesturing toward the rear of the building. “They looked that way because there was someone to see.”

Turning his head to look up at the vision of Mary, Nava added: “Now, I think we have it in the right balance.”