It’s a picture-perfect December afternoon in Pacific Palisades, and the sounds of a neighborhood coming back to life are in the air: the steady drone of jackhammers, the hum of emergency generators, the squeals of contractor pickup trucks loaded with building materials. Nearly a year since the Palisades Fire, the first rebuilt homes are almost done.

The campus of Corpus Christi Church, which burned to the ground the night of Jan. 7, 2025, is fenced off, the mass of tangled debris now cleaned up. The Christmas lights that hung on the trees at the church’s entrance that night are still there, fused to the charred branches.

Corpus Christi will be rebuilt someday, promises the church’s pastor, Msgr. Liam Kidney. But permits, funding, and architectural designs will need to be figured out first.

“See that white house over there? That’s one of our parishioners homes’ being rebuilt,” called out Kidney from the sidewalk in front of the Corpus Christi lot, with a touch of pride. “He’s a builder.”

A few moments later, a black Land Rover slowed down as it approached the church site.

“Is that you, Father Kidney?” shouted a woman in her 30s from the driver’s window. “I can’t tell you how much I miss this church!”

The 81-year-old native of Ireland smiled and yelled out a “Hey there!” She wasn’t the first soccer mom to recognize Kidney during one of his regular visits to the place he’d called home for 26 years.

Like Kidney, most of Corpus Christi’s parishioners lost their homes in the Palisades Fire. Some have relocated to places as close as Brentwood and Manhattan Beach, or as far away as Japan. Others are determined to rebuild and return, despite a backlog of unresolved fire insurance claims and permits to be cleared.

Kidney is also taking the long view, confident that the opportunity of building a new church outweighs the risks.

‘We’re not building for what’s here now,” said Kidney. “There’s nothing here now. We’re building for the future. We have no idea what the future is, but whatever we build has to be for the future.”

But what will the future look like? For the parishes directly affected by the LA wildfires of January 2025, that’s still hard to say.

Another Catholic church that caught fire that week, Sacred Heart in Altadena, suffered $350,000 in wind and fire damage during the Eaton Fire, but was spared thanks to a quick-thinking deacon’s early morning heroics. Most parishioners were at least temporarily displaced, and at least half lost their homes, estimates Sacred Heart pastor Father Gilbert Guzman.

Some were homeowners, including older Black families who’d lived in Altadena all their lives and were hoping to retire comfortably. Guzman fears that many simply “don’t have it in them” to rebuild.

“I can’t see how those who had purchased their homes decades ago could go through this process of rebuilding and affording what it would cost to live here again,” said the priest.

Some of the hardest hit were single young people renting “granny flats” or ADUs. Most have been priced out of renting nearby and were displaced further inland to cities like San Bernardino and Monrovia, said Guzman.

“There are those people who lost their homes, there are people who were out of their homes for nine months,” said Guzman. “Everyone had different experiences. So how do you minister to a community with so many different experiences, but yet so similar?”

Altadena’s other Catholic church, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, was also spared by the Eaton Fire, which got within four blocks. Mass attendance dropped but has steadied since new pastor Father John Kyebasuuta arrived last July. But its school isn’t expected to reopen: a majority of students were permanently displaced by the fire, and only a tiny minority of parents surveyed last year said they’d be able to re-enroll.

“Some parents have told me they have a mortgage to pay on the house that they lost, and they are paying rent where they are right now,” said Kyebasuuta. “How can they afford to put a kid in Catholic school?”

of the historic The Fox Restaurant in Altadena Wednesday, Jan. 7, 2026. The restaurant was established in 1955

where Bowman worked for twenty years as a server and Beard also worked there for 12 years. The restaurant

a local landmark along Lake Avenue near Grocery Outlet burned to the ground during the Eaton fire. (Juanito Holandez Jr.)

A slightly different narrative is emerging at Corpus Christi.

Paola Sessarego was six months into her new job as the parochial elementary school’s principal when the Palisades Fire struck. While her students were forced to enroll in new schools around Southern California, she’s learned to become a principal without a school.

But enough displaced parents are vowing to return to the Palisades and send their children back to Corpus Christi School, which unlike the church, escaped destruction in the fire. Benefactors want to help, and even teachers who’ve gotten new jobs have told Sessarego they want to be hired back.

“I’m surprised at the opportunity that we have to make this better,” said Sessarego, who is working with architects, construction companies, and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles to plan the school’s reopening for the 2026-2027 school year.

Sessarego knows many families will not be returning, but expects new ones will replace them.

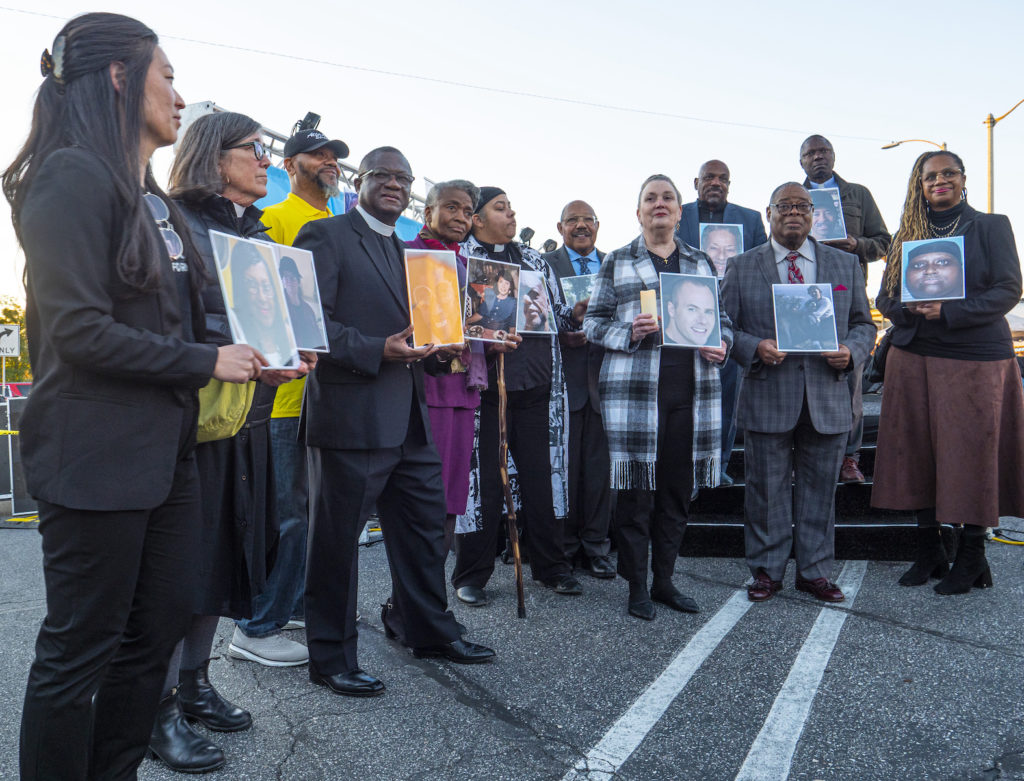

of the ecumenical group is holding a picture of a fire victim. Fr. Kyebasuuta is holding a picture of Victor Shaw. (Juanito Holandez Jr.)

“If you can see a light at the end of the tunnel, it’s that this is an opportunity … to upgrade the school,” said Sessarego. “To make all the classrooms modern, to really upgrade everything, and to make it a really top-notch school.”

One factor working in Corpus Christi’s favor is that it belongs to an abnormally tight-knit community, by Southern California standards. Unlike most LA neighborhoods, almost everything in Pacific Palisades was within walking distance of most people’s homes.

“The beauty of the Palisades is no matter where you went, people were saying ‘Hi’ to you and you were saying ‘Hi’ to people because it’s kind of like Small Town USA,” said Sue Kohl, a local real estate agent.

Kohl had lived in her house on one of Pacific Palisades’ “Alphabet Streets” near Corpus Christi for 32 years before it burned. One year later, her new home is almost completed. She considers herself lucky, knowing that for many fellow Palisades residents, the decision to rebuild depends on things like insurance coverage and age. But she’s seen another important factor at work.

“The people who are deciding to stay and build back, for one thing, are people that have faith that the community will come back,” said Kohl, a Corpus Christi parishioner and the president of the Pacific Palisades Community Council.

“There are families who I know want to come back, and many of them will, even if they’ve taken their children to other neighborhoods, and are in different school systems for two or three more years,” said Kohl. “I have to hope that at the end of that, they’re going to want to come back. I think a lot of them will, but it’s going to take some time.”

Ultimately, the real building project ahead for Catholics in burn areas is the personal one.

“We have to really start building a community again,” said Sessarego.

In the weeks after the fires, the parishes in Altadena and Pacific Palisades used social media and email to help people stay connected. The Sunday after the fires, Father Marcos Gonzalez, pastor of St. Andrew’s in Pasadena, opened his church for Guzman and Sacred Heart parishioners to celebrate an afternoon Mass with Auxiliary Bishop Brian Nunes.

Guzman said the Mass was “one of the most healing experiences I’ve ever witnessed.”

“Afterwards, everybody stayed around for about an hour-and-a-half just hugging and sharing stories, crying together. It was beautiful.”

Meanwhile, Corpus Christi parishioners embraced the label of “Roaming Catholics,” gathering for Sunday Mass at a different Westside LA parish each week. They now have Mass on the campus of Mount Saint Mary University in Brentwood every Sunday, giving parishioners a sense of stability until plans for a new Corpus Christi church start to take shape, and people move back to the Palisades.

“I don’t want to say there’s been a loss of community because we’re all still very much in touch, but there’s a loss of visible community,” said Kohl. “We can’t see each other. We can't walk down the street.”

Since arriving at St. Elizabeth’s in Altadena last summer, Kyebasuuta has looked to build back the sense of community that was lost in the fires. He’s started coffee and donuts after Sunday Masses, and this month a new parish women’s group is launching. He visits parishioners who’ve lost their homes and are now living in other cities. The local St. Vincent de Paul Society chapter continues to distribute groceries at the parish daily.

The priest, originally from Uganda, said that events like weddings, funerals, and first Communions also play a critical role now.

“My children went to school here, I was married here, I did my sacraments here, so for me, this is home,” Kyebasuuta said that people tell him. “Even if they’ve lost their home, they still have that spiritual connection from the past.”

Much like the COVID-19 pandemic, Kidney and Guzman consider the January fires a disruptive event that, while separating people from one another and their church, forced them to reassess what faith was really about.

“I’m believing it more and more that COVID and the fire are an opportunity to come together as God’s people and to rebuild a community,” said Kidney, who noted that he’d seen an increase in confessions since Corpus Christi began hosting the sacrament outdoors during the pandemic.

Guzman said that the fires brought a “real sense of purification” to his parish and allowed them to experience God’s love through the generosity of strangers. But no matter what is or isn’t built, the ultimate lesson has been existential.

“The richest and the poorest all were homeless at the same time, and it gave us a perspective that it is a situational thing that we’re all going through. None of us really owns anything,” said Guzman.

“The suffering has provided a common ground for all of us and a sense of purpose in getting through this. It’s realizing that material things are not everything, that what lasts is love.”