At the start of the school year last fall, the group of kids who’d transferred from nearby public elementary schools to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church School in Oxnard were still learning English, and couldn’t read or identify certain letter sounds.

But a few months later, something had changed. After 90 days of personalized instruction, the students now know letter sounds, can read full sentences, and have a higher level of fluency.

Such turnaround stories are the goal of Solidarity Schools, a three-year initiative aimed at helping students in disadvantaged areas with limited proficiency in English perform at or above grade level in reading and math.

Our Lady of Guadalupe is one of 18 elementary schools in the Archdiocese of LA participating in the initiative, which is also present at six Catholic high schools in the archdiocese. It uses a common curriculum, intervention programs, and professional development to create a “culture of literacy” at schools where literacy doesn’t always come so easily.

Our Lady of Guadalupe principal Lionel Garcia said he’s seen students in the program become more confident, more involved on campus, and more enthusiastic about reading.

“It’s huge for the community, especially for marginalized communities, because it provides accessibility and resources that support all types of learners,” he said. “For a principal, it’s honestly a great initiative. And it works.”

The Solidarity Schools program serves more than 4,000 students and is being launched with more than $2 million in support from the archdiocese and donors, said Paul Escala, senior director and superintendent of Catholic schools.

The initiative was born after Escala’s team discovered that at many archdiocese schools, 70% or more of students were performing below grade level in reading coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

They also noticed a pattern: Many of those underperforming students came from chronically impoverished backgrounds, and in many cases, their schools lacked the proper resources to help.

To launch the program, the Department of Catholic Schools (DCS) started looking for funding and identified schools that had experienced three or more years of below-grade-level performance in reading.

“Christ teaches us that we must find the lost sheep and bring them back to the flock,” said Robert Tagorda, chief academic officer. “That’s what this initiative represents for us. We’re doing it in a way that targets the academic needs of these students.”

The Solidarity Schools program is being rolled out over three years.

At the high school level, the program is focused on boosting math proficiency this year. At elementary schools, it’s mostly focused on implementing Success for All (SFA), a literacy program that provides phonics-based language arts curriculum, coaching, and professional development.

Each week, members of the DCS team overseeing the program’s rollout visit schools to provide feedback, review results, and organize materials.

“The work that we’re doing with these schools really speaks to what our faith calls us to do,” said Gina Aguilar, Ed.D., managing director of the DCS Academic Excellence team. “To journey together, and support our students, and help them become who God called them to be.”

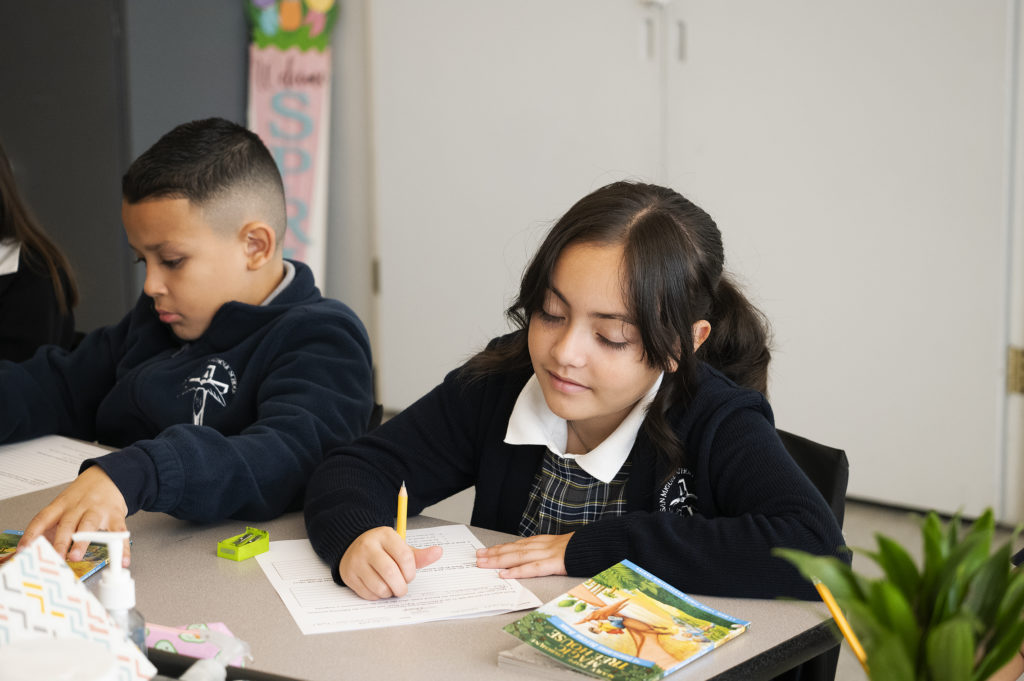

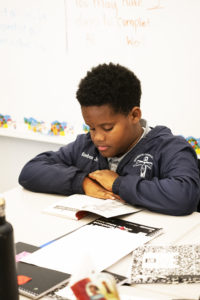

For elementary students, the program emphasizes letting students learn at their own pace while continuously challenging them, even as their literacy skills improve.

Christian C., a fifth-grader at San Miguel Catholic School in Watts, said he’s learned new words this year through SFA that are strengthening his vocabulary and reading comprehension skills.

“Now I can use bigger words, longer words to make better sentences,” he said.

Valery R., also a fifth-grader at San Miguel, said that while her reading scores have always been solid, SFA challenges her to achieve even higher.

“I feel like SFA is just a great way to impact and expand our reading level,” she said.

In the program’s second year, students will also get help with math, as well as continued literacy support.

In the third year, the department will focus on making the program permanent at the schools before tapering off its daily support.

Its supporters say Solidarity Schools goes beyond academic growth in the classroom: By targeting attendance, behavior, and parent and family involvement, it also gives valuable skills to help break the cycle of poverty in which some of their families live.

At least two-thirds of Solidarity School participants come from low-income backgrounds, and 94% are Black or Latino, according to DCS.

Many live in historically underserved communities, where access to quality housing, health care, and other services critical to families’ stability are limited, Tagorda said.

Many also come from families still reeling financially from the COVID-19 pandemic, which can create instability at home and detract from student performance, he added.

So far, testing data shows that Solidarity Schools students are making “huge” gains in literacy, Aguilar said. In just the first three months of the program, the percentage of participants reading at or above grade level increased by eight points.

Studies also show that the number of elementary students needing “urgent intervention” is down and schools are meeting the program’s implementation goals.

At St. Malachy School in South LA, Rosio Orozco — who serves as both the principal and a full-time fifth-grade teacher — said the school has seen major improvements in student behavior and achievement since joining the program.

Orozco said she’s changed her classroom management style after participating in the program. Instead of “hovering” over students to ensure they stay on task, she’s now able to let them set their own learning routine.

“There’s no need for reminders anymore because they are so involved in it and understand how the process works,” said Orozco, who’s been teaching for more than 25 years. “That allows me to take a step back and just see everything come alive on its own.”

At San Miguel, Principal Maryann Davis said she’s also noticed that students are more excited about reading.

“It’s become a community where everybody’s looking out for each other,” she said. “The students are being responsible for each other because they care about each other. They’re working in teams and they want their team to be successful.”

Looking toward the future, Escala said the department has already been contacted by other schools interested in seeking to join the Solidarity Schools program.

Escala said he hopes the program grows, because the more students that are reached, the more lives can be changed.

“In my heart, I believe that this is where our job is as a church, as a ministry,” he said. “Ending the cycle of poverty for many children by unlocking the door of literacy is going to be the biggest upside of this project.”