“I tell you that one greater than the temple is here. But if you knew what this means, ‘I desire mercy not sacrifice,’ you would never have condemned the innocent.” — Matthew 12: 6–7

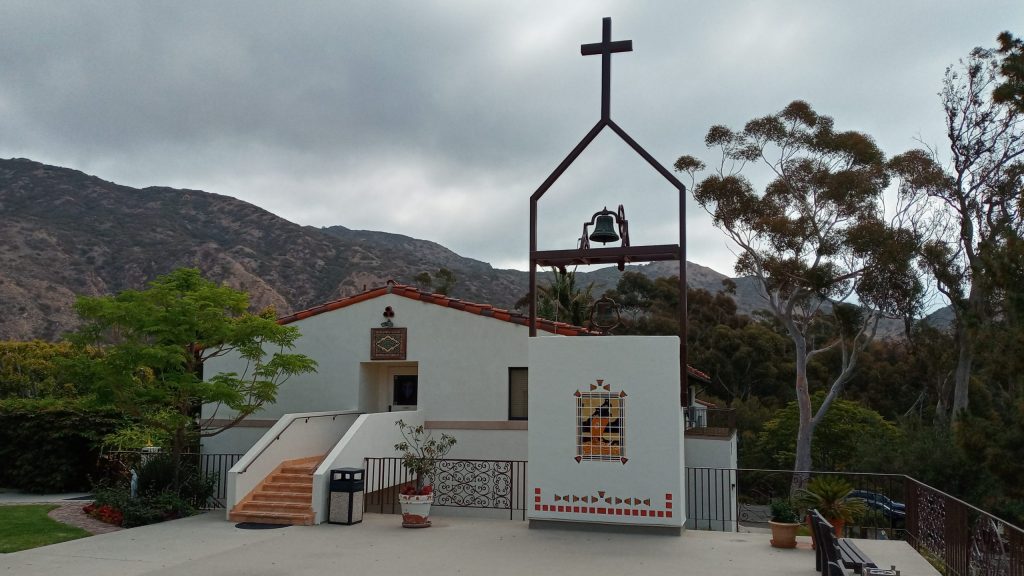

Serra Retreat House in Malibu reminds me of a ship on land. The old, elegant property (constructed by a woman in the 1920s as her dream home, only to see her husband die suddenly before construction was finished) sits atop a narrow promontory between two steep gorges facing the sea.

The “prow” of this ship is called “the Point.” I couldn’t keep myself from that lookout the whole weekend of my retreat on Memorial Day weekend. The view of the Pacific is the best I have ever known, and I’ve known a few.

The 13,000-acre Rancho Malibu, stretching from Topanga Canyon to Port Hueneme, was given in 1804 as a land grant by Gov. José Joaquín de Arrillaga to Jose Tapia, a soldier in the original 1775 DeAnza Expedition to Alta California. Four owners had it before the Rindge family took over in the 1890s.

When they assumed control over the 26-acre Serra property in 1942, the Franciscans placed at the head of the Point a tall cross, remembering the Cross of Damiano that St. Francis repaired in Assisi. Just behind the cross is a statue of St. Junípero Serra, half his body pulled down by a recent vandal, his ceramic toes peeking out from a Franciscan brown hood. Ah, how we need St. Francis’ repairing hands again!

My family has ties to Serra Retreat that go back a half-century. It amazes me how much of the natural beauty of the place escaped me when I was 17, the last time I was in a retreat in Malibu as a high school senior at Crespi Carmelite High School in Encino. A teenage boy at an all-boys school’s interests are cigarettes, poker, and girls—not in that order. They were certainly mine.

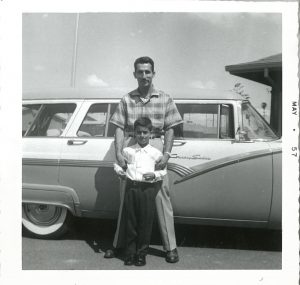

But Serra Retreat holds another, better fixation for me on the far side of middle age. My father joined a men’s club retreat there from Our Lady of Grace parish in Encino each year for 20 years. Whenever I would drive down Malibu Canyon Road as it bent to the sea on our way to body surf or board surf, I would glance south at the high ridge of Serra and think to myself, “Dad was there.”

Now, for the first time in four decades, I returned to trace his steps, this time to understand his faith. Did it waiver when he had to deal with the mental illness of his only daughter who would take her own life? I thought to myself in my many trips to the Point: Can I answer that one question before I leave?

Walking the serene grounds under every kind of palm and oak, along bougainvillea red and plumbago pale blue, I wondered what compelled Aref Orfalea to the Serra knoll. The short answer: His next-door neighbor Chuck O’Neill’s invitation. They were close; both died young, though Chuck’s was a natural death. But what really may have driven Aref to that radical, quiet remove was disruption, jarring changes in his own life that needed reflection.

He was a women’s garment manufacturer; styling four seasonal lines plus holidays was often an exhausting profession. Success was never assured. You were only as good as your last “line.” Two times he had to close his business and start over; a third time an owner he had joined as second in command was extremely offensive and he left, shaken, just before that rag shop went under, too. Serra Retreat was perhaps a place he associated with starting over.

I understood that. Change was in the wind for our family, too. Our house was up for sale in Washington, D.C., and I had come back to plant the flag for our move back to California, with a new job administering to disaster zones. The potential for good is large, as is the risk of hazard and heartbreak. Aref’s work life and mine had need of prayerful retreat.

Finally, my father and mother both dealt with the 10-year decline of my sister into debilitating mental illness. I think it is safe to say that seeing your child helpless against destructive and self-destructive acts is one of the most painful plights a parent can face. Medications are somewhat better now, but 30 years ago, they did not help my sister.

My own family has a special-gifts son named Luke. Ninety-nine percent of the time he is the most incredible, loving person, with a vast memory and huge heart. He keeps track of family and friends’ birthdays, sends greetings, recalls exactly what you ordered for dinner at what restaurant in what month of what year. He goes to Mass faithfully and attends alone if I am not there, and does so, he told a priest, “out of respect.” But at times his anxieties present a challenge, though not even close to those of my schizophrenic sister.

Though what Aref faced, I stress, was far more severe, we both trod the path of a very special child.

There were about 30 of us from various parts of Southern California at the Serra weekend retreat, only the second one at Serra since the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020. The staff and Father Charles Smiech, Serra’s priest-in-residence, were almost as happy to see us as we were to be there.

We said vespers, or evening prayers, which included the “Magnificat,” the Canticle of Mary. We ended each night with, “May the Lord bless us, protect us from evil, and bring us to everlasting life. Amen.” The next morning, Saturday, our prayer was urgent: “Lord, open my lips, and my mouth will proclaim your praise.”

“The Franciscan Way” was a topic of discussion, including the centrality of Francis’ concern for the homeless right at the start of his apostolate. One participant had seen a statue recently of a homeless person with holes in the hands and feet. The notion that Jesus is in every homeless person was conveyed repeatedly. I thought of my sister’s difficulty retaining housing on her own; in the final chapter of her life, she came home to Tarzana where Aref and Rose fatefully did not turn her out.

In the discussion of compassion, I brought up the great poem by Pulitzer-prizewinning American poet James Wright (a late convert to Catholicism) entitled, “Saint Judas.” It begins: “When I went out to kill myself, I caught / a pack of hoodlums beating up a man. / Running to spare his suffering, I forgot / My name, / My number, how my day began.” The poems ends, “Flayed without hope / I held the man for nothing in my arms.”

We consider Judas doomed (even Christ strangely said it was better that he not be born), but Wright forces us to consider what might have happened on the way to Judas’ self-hanging and that even in the depths of his despair, could he have done something that may have redeemed him? (Christ also said, “With God, all things are possible.”) My takeaway: Give up on no one, least of all yourself. Because God isn’t giving up on you.

Prayer was recommended to our group time and again. Common tasks such as sweeping the floor, vacuuming rugs, or watering the plants can be a form of prayer. “What breaks your heart? What makes your heart beat faster?” We were asked to consider these questions, and the answers would reveal where we should head. Exactly there God would take us and reveal to us what role we might have in improving the world.

Contemplating Francis, the audience identified him with many things: holy poverty, loving everything and everyone, peace, anger at injustice, incredible listener, burning love, bravery, constant conversion, gentleness, unselfishness.

One speaker encouraged us to be on alert for the good with a discerning eye. Aref saw hell. God saw good, which is to say, Himself, in him. “Am I up to such a thing?” I asked silently.

At Mass Saturday afternoon, Father Charles reminded us that we had all been through a very strange, traumatic year with COVID-19, one that isolated us beyond anything Franciscan. But we did develop a deeper recognition and love for bird calls, for things close to home, including family.

The talks, the prayer, and the natural beauty all led me deeper on my quest for the answer to my question about my father, Aref, his extraordinary trial, and his faith. His footsteps seemed to be everywhere.

I felt him closely by me under the cross at the Point lit up at night for any ship off course to see. I imagined him walking with me into and out of a labyrinth, in which I felt disoriented on the periphery, but found myself closer to God at the center. I felt him with me looking out my window above the Spanish tiled roof to the sea. I felt him kneeling as I kneeled. And most of all, when I spread my arms wide at the Pacific, I felt him embrace me.

Did he keep the faith even to face a bitter end at the hand of the one he felt for most? He had been a paratrooper in World War II. He jumped with faith — into air and into life. I concluded, staring at the infinite Pacific, that his faith held that fateful day when he could have taken a pass on responsibilities and the awful demands of love. His faith was the prow of a ship sailing into the night and the mist. I pray to follow him.

On Sunday, I walked to the car. My father got in at shotgun, with no gun.