“Let me give you an example from my own personal life,” says Diane Vines, dean of nursing at Mount St. Mary’s University. She’s sitting at a conference table with Rochelle Ko, a senior in the BSN (Bachelor of Science in Nursing) program, and me. We’re on the first floor of one of the restored old mansions on the Doheny campus, off West Adams Boulevard. The subject is palliative and hospice care. With Governor Jerry Brown signing the so-called “death-with-dignity” act into law last week, end-of-life issues have once again been highlighted in California.

The dean is talking about her 99-year-old father, Howard, who died in April. After being hospitalized a couple times, he was discharged to his assisted-living apartment near Clearwater, Florida. He told her on the phone, “I’ve outlived my usefulness. I’m ready to go.”

When he chose to stop drinking fluids and eating, she arranged for hospice care. It wasn’t long before the hospice nurse called back, saying it would take about 48 hours for her father to die. Vines got on a red-eye flight, while the nurse in Florida told her father “Diane’s on her way.”

“I know he knew when I got there,” she recalls. “So we stood and talked to him. And about two hours later, the nurse said, ‘I think he’s passing.’ I stood on one side, she stood on the other side. I rubbed his head and she rubbed his arm. And I told him it was OK to go — that my mother was waiting for him. And the hospice nurse was saying, ‘It’s OK, Howard. We understand. You’re ready to die and it’s OK to leave us.’”

Which Howard Welch did.

“We waited a couple of seconds before the nurse said, ‘I think he’s passed.’ Then she said, ‘We’ll wait an hour before we call the doctor because otherwise they have to do saving measures.’ We called the doctor, and they took him straight to the funeral home,” says Vines.

Two weeks later she got a call from the hospice program’s supervisor. He asked how she was doing. She said she was back to her routine in Los Angeles, but still in sort of a daze. A month later, the supervisor called again asking about how she was handling the death of her father. She said “at the moment,” 6:30 a.m. L.A. time — 9:30 back in Florida — was when they talked every morning on the phone. So it was in the early morning when she really missed him.

“And he said, ‘Why aren’t you talking to him still?’ I said, ‘Oh, my, of course. Because he’s in heaven, I know, and he’s looking down.’”

After a moment, Vines adds, “So it’s that kind of spiritual approach that I think is helpful to everybody. It certainly was helpful for me, but I think it really was also helpful for my dad.

“So I learned a lot,” she reports. “Because when I was in nursing school, there wasn’t such a thing. And I came back with a new appreciation of what hospice nurses do. Palliative care nurses are similar because they relieve the pain and stress to the family, too.”

nLaw changes doctor’s role

Gov. Jerry Brown’s signing of the End of Life Option Act — or what opponents call the “physician-assisted suicide law” — on Oct. 5 brings up

some weighty theological and philosophical questions that would confound Hippocrates: “Do people in pain or anticipating pain have the right to kill themselves?” “What’s the role now of physicians in helping their patients die?”

Roberto Dell’Oro, director of Loyola Marymount University’s Bioethics Institute, believes the latter is the big issue. And he posed a surprising question during my interview: “Does the medical community even have a responsibility to care for the pain of a seriously ill or dying patient?”

“The answer is certainly ‘yes,’” he said. “The description of the medical profession has to do with relieving pain and suffering, not with terminating life.”

The professor in the school’s theological studies department says the two — the commitment to alleviate pain and healing the patient or the commitment to aid-in-dying — are “pretty much at odds with one another.”

For years, doctors have performed what’s known as “terminal sedation,” not to end somebody’s life but to make their patients more comfortable. Estimates of very seriously ill patients being terminally sedated have ranged from 2 to more than 50 percent. But the subject is rarely brought up in public.

One of the pillars it rests on goes back to the “double-effect” rule attributed to St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, which justifies killing in times of war and for self-defense.

Regarding end-of-life matters, the principle posits that even when there’s a foreseeable bad outcome (death), it is morally acceptable if the intentional good outcome (relief of pain) outweighs it.

“It’s a matter of stopping feeding and increasing pain medication that leaves you to die,” explained Dell’Oro. “It’s not the practice of assisted suicide. Because the motivation, the intentionality of the physician remains the alleviation of pain, not the killing of the patient. That’s the fundamental difference.”

He points out that California’s new law radically changes the medical role of doctors from healing and relieving suffering to also helping their patients die. “Those are completely different commitments,” he said, “and they still don’t address terminal sedation.”

What’s needed, according to the bioethicist, is for doctors dealing with these heady end-of-life issues to have a “space for exceptions” in concrete cases — not a state statue. Right now many still face a degree of “fear and trembling” when it comes to terminal sedation.

Why? Because there aren’t real guidelines or protocols.

“Doctors are not sure that they can do everything that they think they could do and to go as far as they would want in the alleviation of pain,” he explained.

Dell’Oro doesn’t believe the issue can be solved by simply changing the law, the way California, along with Oregon, Washington, Vermont and Montana have. (Montana’s law came about by a court decision.) He says it pushes the “intentionality” of doctors to the wrong place. “And rather than maintaining their own commitment to the lives of patients, it compromises that commitment,” he said. “It makes their own commitment to either life or death somewhat equal.”

He points out another argument against the new California law, which Archbishop José H. Gomez raised recently in his Tidings column. Evidence from Holland and Belgium, European countries which have had assisted suicide and euthanasia laws since the early 2000s, shows the statues have morphed from a patient’s decision to more involuntary “default” positions for the marginalized.

Yet the LMU professor’s main argument against the new law is really philosophical. “So is a doctor an agent of life, or is a doctor an agent of death?” mused Dell’Oro.

n‘Transformative’

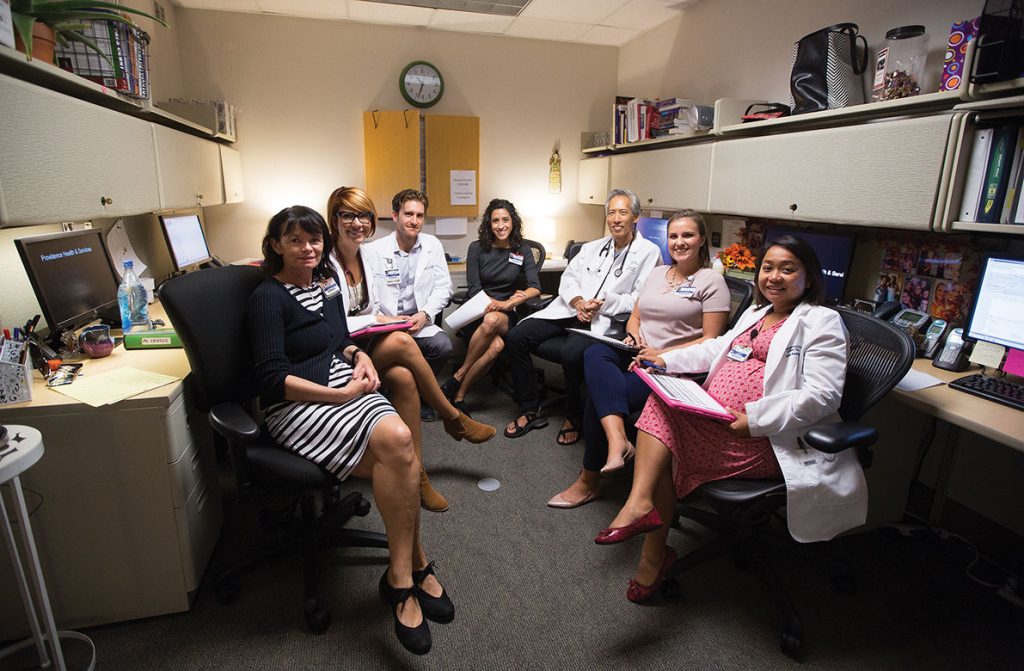

For Dr. Glen Komatsu, it’s not quite that black and white. “When you actually take care of people at the end of life and when you go out and hear their stories and see the suffering, it’s just not clear cut,” the regional chief medical officer for palliative care at Providence Health and Services California told me.

The palliative specialist oversees palliative care programs at six of the Catholic health care group’s hospitals. He’s also the medical director of Trinity Kids’ Care, the only pediatric hospice and palliative care program for children in California, as well as the chief medical officer of Providence Trinity Care Hospice for adults and children.

He brings up how medicine in the United States is focused on diagnosing and curing disease. “When people go to doctors, they want a cure,” he said, “and anything less than a cure is not acceptable. But as we all know, none of us are immortal. I haven’t met anybody immortal yet. And so all of us are going to die.”

After a moment he adds how American health care workers, especially doctors, need to understand that “healing can happen even when curing is not possible. Healing is different than curing. Curing is when you don’t want things to change. You want your injury fixed, your illness eradicated, which depends on the skill of the practitioner.”

But healing is a different phenomenon, says the physician, with the power to heal residing within the patient.

“It’s a transformative process where the person becomes transformed by their illness — becomes a different person, develops a different identity,” said Dr. Komatsu. “And in some cases, not all, but in many cases patients can come to terms with that new identity and appreciate life for what it’s offering them. It’s a stance of gratitude, awareness, mindfulness. So that’s how we see people who are healed even as they’re dying.”

That’s the goal of both his palliative and hospice care programs, which he calls the “miracle.” It boils down to creating the conditions for the patient and family to do the hard work of changing. He says not all patients get there. Some die difficult deaths, “kicking and screaming” in ICUs (intensive care units) with their blood vessels and orifices hooked up to IVs, tubes and monitoring machines.

“A lot of them say, ‘I’m mad at God’— especially I hear that in the pediatric population,” he said. “Because there’s never a good reason for a child to die. I mean, it’s so tragic when a child dies of any age — even if the child is 50 and the parents are 75. So sometimes there are no words. Sometimes it’s not possible to get the healing.”

But Dr. Komatsu and his teams just keep “showing up” to support dying or seriously ill patients and their families. He says it’s important for patients to see “we’re not afraid to witness their suffering and stand beside them.”

What he and his colleagues are actually trying to do is change the whole paradigm of western medicine to whole-person care, where not only physical but psychological, emotional, social and spiritual pain is addressed. And that’s why they need a multidisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, psychologists, social workers and clergy.

When I asked about the End of Life Option Act becoming law, Dr. Komatsu sighed deeply. “I don’t think it’s great public policy,” he said. “But I just think the reality is people want this choice, and they want excellent palliative care and hospice care. They want all of the above.”

After a pause, the physician added, “My colleagues in Catholic health care have been living with it in Oregon for years. And all of the hospices there, whether they’re Catholic or not, have said they could not participate in doctor-assisted suicide and they would not abandon their patients. They would continue to help with mortuary arrangements and help families with bereavement.

“And I think that should be our stance as well,” said Dr. Komatsu. “We’re going to be there for patients no matter what.”

nNew paradigm

After talking to the dean of nursing and a student at Mount St. Mary’s Doheny campus, I walked back to my car, turning side-to-side to check out the restored mansions one last time. But I was also thinking about the peaceful death Diane Vines’ 99-year-old dad had with hospice care. Before Howard Welch died in his assisted-living apartment in Florida, he told her, “I’ve outlived my usefulness.”

At the end of her dad’s life last April, she was back there rubbing his head. The hospice nurse was also at his side, rubbing his arms and saying, “It’s OK, Howard. We understand. You’re ready to die, and it’s OK to leave us.”

My nearly 90-year-old mother, Lois Dellinger, died years ago in a sterile hospital bed in upstate New York, connected to all kinds of life-monitoring and life-sustaining tubes and equipment. And her weeks of dragged-out dying happened way more like what Dr. Komatsu described as “kicking and screaming.”

With a chuckle, he’d told me, “None of us are immortal. I haven’t met anybody immortal. … Yet here in the U.S., death is to be avoided at all costs. And we think if we live long enough medicine will figure out a cure for cancer, dementia, everything that ails us.”

Then the physician added, “So we have to offer another perspective, a different paradigm. That’s what hospice and palliative care do.”