A diabetic middle-aged woman in South Los Angeles told me — after losing five toes, her right foot and ankle, along with nearly half her leg — that she was doing “just fine.” That’s what she said, even though the ugly sore on the sole of her good foot wasn’t healing, forcing her to use a wheelchair more and more, fearing another amputation was inevitable.

When asked weren’t there treatment options for the diabetes-related condition, like aggressive wound care from a medical specialist, she just shrugged. But her expression said that was about as likely as her hitting the next SuperLotto Plus.

That attitude doesn’t surprise Dr. Carl Stevens, lead author of a recent UCLA study finding that poor people with diabetes are up to 10 times more likely to lose a limb than wealthier patients. “When you have diabetes, where you live directly relates to whether you’ll lose a limb in the disease,” he said. “Millions of Californians have undergone preventable amputations due to poorly managed diabetes.”

Today Stevens is a health sciences clinical professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. But for 30 years he worked in the emergency room at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance.

“I’ve stood at the bedsides of diabetic patients and listened to the surgical residents say, ‘We have to cut your foot off to save your life,’” he recalled. “These patients are often the family breadwinners and parents of young children — people with many productive years ahead of them.

“This is an intolerable health disparity.”

‘Hot Spots’

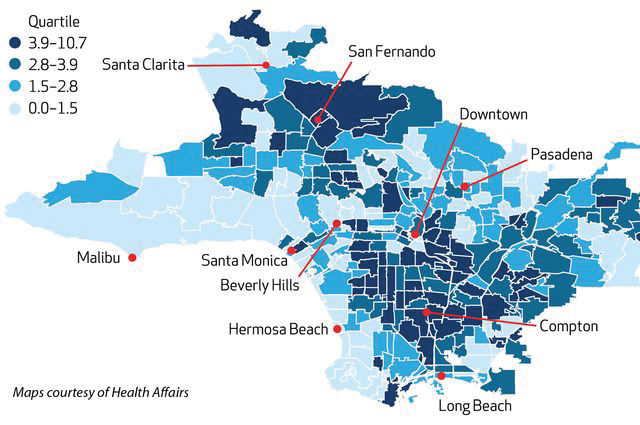

Location does indeed matter, with amputation “hot spots” in Los Angeles County, including broad swaths of South Los Angeles and East L.A. as well as San Fernando and Compton clearly identified.

In those locales, lower limbs were amputated in as many as 10.7 out of 1,000 diabetic adults, 45 and over. This was compared to no more than 1.5 diabetics per 1,000 losing a lower limb in Malibu, Beverly Hills and Santa Clarita.

While African Americans made up less than 6 percent of diabetics in the state, they accounted for nearly 13 percent of those getting amputations in 2009, the year data was collected. Asians, on the other hand, made up 12 percent of the diabetic population, but had less than 5 percent of diabetes-related amputations.

“Race certainly plays a part,” Stevens told The Tidings. “But so does income, education, access to healthy food, dietary patterns and just cultural issues of seeking care and whether you have a relationship with a physician or not. So race is a factor, but I wouldn’t highlight that as THE factor.”

The raw human figures for 2009 were gruesome: nearly 8,000 legs, feet and toes were surgically removed from 6,800 diabetics in California, including roughly 1,000 patients having two or more amputations. That averaged out to 20 diabetic Californians every day undergoing these radical, life-changing operations.

“I think we put those figures into the press release because it gives people a sense of a scale of the disability that’s happening here,” Stevens explained. “You know, it’s pretty bad. I think if we had other health problems on that scale, you’d see an immediate response. People would view it as a crisis.”

To track diabetic amputations by California ZIP codes, the researchers looked at U.S. Census Bureau data on household incomes along with discharge data from the state’s hospitals. This information was then cross-referenced with findings from a UCLA health interview survey that estimated the number of Californians with diabetes in low-income areas.

The result was a series of maps showing diabetes-related amputation rates by neighborhoods for patients 45 and above.

“Our main goal was to put this issue on the map and get it in front of health policy makers,” said Stevens. “We spend so much on healthcare in the United States, way more than any other country, and to have this kind of preventable morbidity, I think, really should give people pause and make them think deeply about what we can do.

“The health care debate has become so polarized and so politicized, and there’s a lot of discussions: ‘Well, is health care a right or a privilege?’ We hope our findings would say, ‘Whatever you believe politically, the preventable loss of a limb often in the middle of the working years of a productive member of society transcends politics.”

Church’s ‘enormous’ role

The physician and researcher praises the Affordable Care Act for expanding health insurance and care through Medi-Cal and private insurance to some 3 million mostly poor people in California. He’s convinced if the UCLA researchers looked at the state’s diabetes population today, there would be a lot less disparity in amputation rates. And he hopes the investigation’s findings spur other state policymakers nationwide to do likewise.

“What the act doesn’t do — and this is what I think faith-based organizations like the Catholic Church can really play an important role in — is community outreach to educate people about how to take a more active role in the management of their own disease,” Stevens pointed out. “Because the key to preventing these amputations is to be very vigilant about the developing of ulcers on the feet.

“When a diabetic patient develops a foot ulcer, that’s what eventually leads to an amputation if it’s not managed well. But if people can, on the one hand, prevent those by keeping their sugar under control and their feet inspected frequently, and if an ulcer does develop, go see a doctor before it’s badly infected. That will really cut down on amputations.”

Moreover, he points out that in a typical Catholic parish there are probably diabetic members who are expert at managing their own diabetes, while others are struggling. So hooking up the two could be a “very effective” grassroots health-care effort preventing needless amputations. He says it’s akin to the “promotoras” model used in Texas and New York, where lay health workers are trained to explain to others with the same chronic disease what they need to do to avoid further complications.

“I actually think that the community-based organizations are an important key to this,” observed Stevens. “And I think the Church can play an enormous role in that.”