A paraplegic former gang member-turned-hospital chaplain enters the Friars of the Sick Poor. Wearing a dark brown robe, with the Virgin of Guadalupe’s image sown in white thread on the right side of his chest, Brother Cesar John Paul Galan’s right hand covers his face while he vows in front of the Blessed Sacrament behind the altar. Eyes closed. He might want to kneel, but he cannot. He cannot move, in fact, from his waist down; he is in a wheelchair.

Behind the altar where he is reflecting are his family and a group of his closest friends: Friars of the Sick Poor, diocesan priests, Jesuit novices, and women religious from different communities. Ten years ago his friends were very different: gang members.

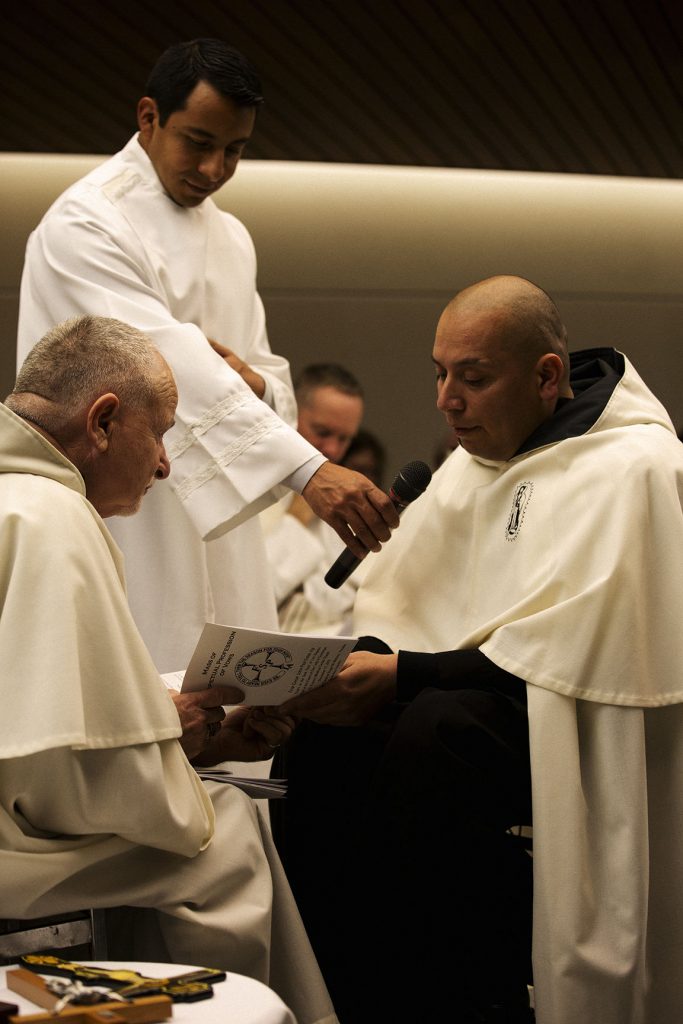

But on this day — December 11, the eve of the Feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe — Cesar, 39, cannot contain his joy, nor can he believe what is happening in his life. He is professing his first vows of poverty, chastity, obedience and self-sufficiency. He is now a member of the Friars of the Sick Poor and ministers as a chaplain at St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood. It is the same hospital in whose trauma room he and his older brother Hector landed on an April night in 2001. Cesar fought for his life; Hector was already brain-dead.

‘I might as well join a gang’

At the age of 14 or 15, Cesar Galan was “full of pride,” thinking that the tougher he looked the better. Men don’t cry, his father taught him.

His father, who held multiple jobs mowing lawns and as a janitor to care for his family of 10 after emigrating from Mexico, also taught him to work. At 14 Cesar would accompany his father to work at rich neighborhoods; that gave him an excuse to not study. Cesar’s parents also stressed attending Mass, especially the midnight Christmas Mass and the celebration of the Virgin of Guadalupe. But all that faded away, he recalls when “I started feeling I was Superman.”

His best friends in the neighborhood, the same ones he had met at elementary schools, were the ones who introduced him to the gangster life. He was walking home from junior high one day with his friends when they were hit by several bottles thrown by people who assumed they were gang members. Cesar was surprised. He had done nothing wrong, but a friend told him the attackers viewed them as gangsters, just because they lived on the same streets.

“That day I thought, ‘I might as well join a gang and get protection because people already viewed us as gang bangers.’”

Right after that incident he joined a gang; he knew right then “there was no backing out.” Still, he chose to ignore that he was about to begin “a life of pain and suffering” that worsened with the killing of his closest friend, also a “homie.” He says he still “talks” with his friend, who he believes is with God. Today, talking about his friend, Cesar’s demeanor changes from happiness to sadness mixed with tenderness; tears sneak through the corners of his eyes that suddenly redden. But back then, all he felt was “anger, hate. I wanted people to feel the same I was feeling: a lot of pain.”

He became senseless and was willing to give everything for his “homies.” Although he did not use drugs, he was around many people who did, and many who went back and forth from jail. From the nearly 30 friends he had at the time, he says today, 15 are serving time in prison, 10 are buried and only about three are “doing good.” He managed to get jobs, get married, and had two sons with his wife. They had just separated the day he and his brother Hector (who was not gang-affiliated) had an altercation with a gang member outside his house. The latter returned with a gun and shot them, leaving Hector dead and Cesar — who still carries a bullet in his spinal cord and another in his chest — a paraplegic.

‘Teach me how to fly’

Brother Richard Hirbe was called to the trauma center that night in April 2001. He had already been St. Francis chaplain for 13 years and, as the person in charge of spiritual care, he was given the task of disclosing to Cesar the “tragic and devastating news.” Little did both men know this encounter would change and unite their lives forever. First, Brother Hirbe told Cesar he needed to “let his brother go; let him be free.” Cesar agreed. His brother’s bed was wheeled next to Cesar’s, who grabbed him by the hand to bid his last farewell. Then, Brother Hirbe broke more devastating news to Cesar: He would not be able to walk again.

What happened next was the breakthrough for both men.

“Cesar grabbed my shirt,” says Brother Hirbe, “and told me, ‘If I will never be able to walk, then teach me how to fly.’”

Those words resonated in Brother Hirbe’s mind and heart, and for the next year he visited Cesar every single day at La Palma Hospital, where he did his rehabilitation. It was a time in which he “turned his suffering into redemption. He turned something ugly into something beautiful,” said Brother Hirbe. Inspired by the young man’s transformation, the brother approached Cardinal Roger Mahony to “open a flight school to teach boys how to fly.”

This is how the Friars of the Sick Poor was founded, to “offer hope, turn pain and suffering into redemption and bring them closer to the church.”

Today, the Friars of the Sick Poor have nine members, including two postulants and an inquirer. In 2008 it was recognized as a Public Association of Consecrated Life, in view of becoming in the future a Secular Institute of Diocesan Right.

‘A new awakening’

Brother Richard Hirbe had taken his first vows with the Capuchin Franciscans in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, back in 1976. But in the 1980s he was “led back” to California, where he was born and raised. He then got involved in hospice ministry. The encounter with Cesar, he admits, “was a new awakening to go deeper into the pain of others. Cesar trained me, not the other way around,” Brother Hirbe says humbly.

Today Brother Hirbe starts his rounds at 4 a.m. visiting mostly those affected by drive-by shootings, and ends at 4 p.m. Brother Cesar ministers mostly to the same population.

“Mary shows us how to follow Christ, how to live the vows,” said Friar of the Sick Poor Father John Sigler, in his homily during the Dec. 11 profession of vows Mass at St. Francis Chapel over which he presided.

“Our Blessed Mother also had this sense of awe: Why me? What did I do wrong?” he said as a comparison with Brother Cesar’s life. The Virgin of Guadalupe is the Friars’ patroness.

“But she continued to live with such humility; she too would live in poverty today, which means serving in the midst of the difficulties. She chose to continue to serve and Brother Cesar chose to continue to serve our Lord; to help his parents and help raise his sons.”

When his youngest son turns 18 in three more years, Brother Cesar said he would like to enter St. John’s Seminary to become a priest.

“Muy orgullosa (very proud) of him,” says Luisa Galan, Brother Cesar’s mother, of her son’s decision to join the Friars. “I never expected that one of my sons would choose this way. He [Cesar] has taught us a great lesson.”

“This is wonderful!” exclaims his youngest sister Gaby. “He used to be so travieso (naughty) and it was so horrible when all that happened to him and my brother Hector. Now we are a lot closer than before.”

And Cesar is equally close to Brother Hirbe’s heart. “When we look back 100 years from now, we will see that Cesar was the founder [of the Friars of the Sick Poor] and I was just His instrument.”