Through all the years of my childhood, widows were just next door. The lady in the apartment behind us was very old, lived alone, spoke no English, and always wore black, but I don’t recall ever seeing her without a smile. Based entirely on her expression, I have to assume the things she said to me were kind. I couldn’t understand a word of Italian.

When I was in fifth grade, we moved to a proper house, and a widow occupied the tidy place next to ours. She had lost her husband many years before in the mining disaster that was legendary in our town. Her yard was immaculate, her house well kept. When I was hawking stuff for school fundraisers, I could count on her to be my first customer. When I shoveled her walk, I knew she would pay me well.

The widows of my childhood were generous like the widow of Zarephath and like the Gospel widow who put her two small coins into the treasury. In that sense, they confirmed the data of revelation. But only in that sense.

Almost everywhere else in the Bible, widows appear as a symbol of misery. In the Law of Moses, you’ll find frequent reference to “the sojourner, the fatherless, and the widow” (e.g., Deuteronomy 27:19). These are classes of people who have no stable home or regular means of support.

In both the Old Testament and the New, widowhood is a synonym for poverty, social isolation, and vulnerability. They are a protected class in the law — but we can assume that their legal protection was routinely ignored, because the prophets raged often against this particular injustice (Ezekiel 22:7, Malachi 3:5).

Even in the New Testament, just moments after the founding of the Church, the first Christians settled into the customary neglect of widows (Acts 6:1).

So why didn’t any of our neighborhood widows look oppressed or destitute?

It has everything to do with the Christian revolution. In the beatitudes, the constitution for his kingdom, Jesus took conditions that were formerly accursed and declared them now to be blessed: “Blessed are the poor … Blessed are those who mourn” (Matthew 5:3–4). These were, in fact, the defining conditions of widows in Jesus’ time. They were bereft and impoverished. Jesus knew this because he was the only son of a widow, and his choice to be a wandering rabbi would have dire implications for his mother’s life.

Yet his mother never faulted him for this. In fact, she left behind the poverty she had known and took up the more radical poverty of her son, who had “nowhere to lay his head” (Matthew 8:20).

We have no record of her complaining about her lot. In fact, she seems serene as she provokes the launch of Jesus’ ministry. She simply observes, in a moment of crisis, “They have no wine” for the wedding feast; and then she says to the bystanders, “Do whatever he tells you.”

As the Gospel unfolds, the widow Mary emerges as the model disciple. She is close to Jesus to the last.

Like the other heroic widows of the Bible — like the widow of Zarephath and the widow in the treasury — she has little, but she gives everything she has. And, as the beatitudes promise, she is blessed: the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Blessed Widow Mary.

The sacred writings bear witness to the Church’s concern for widows. Visit them in their affliction, says St. James (1:27). But that’s really no different from the Old Testament commands, which were ignored.

What’s revolutionary in the New Testament is the choice for widowhood. What’s new is the existence of a consecrated order within the Church of women who voluntarily bore the hardships of widowhood. The Apostle to the Gentiles urges widows to take up this life with gusto “and remain single as I do” (1 Corinthians 7:8). In the First Letter to Timothy, we find this life described and prescribed in detail. It is a life of constant prayer, work, and hope.

This must have arrived as scandalous in the Gentile world. It had not been long since Caesar Augustus had enacted laws requiring widows to remarry, for the good of the state. Now came Christianity declaring that widows should freely do as God bid them to do.

This order of widows seems to have been extremely popular. It appears often in the documentary record of the early Church. St. Ignatius of Antioch, writing around A.D. 107, referred to its members as “the virgins known as widows,” so renowned were they for their chastity. His contemporary St. Polycarp of Smyrna compared them to “the altars of God.” Indeed, the third-century “Didascalia Apostolorum,” which, among other things, sets out the duties and responsibilities of laypeople, bishops, and widows, decreed that widows should be revered like “the altar of sacrifice.”

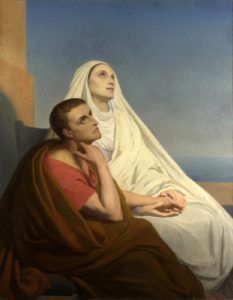

The great Fathers — Sts. Basil, Ambrose, Jerome, Augustine, Chrysostom — wrote letters of counsel to consecrated widows. In Rome and Antioch (two cities for which we have reliable statistics) the order of widows counted thousands of members.

It was liberating. Traditional Roman society offered women no place of their own. A pagan woman found her identity in the men in her life: her father, her husband, and her sons. If she had no man, she was no one. She had no face before the law. She could not even testify in court. There was no flourishing of women in classical antiquity.

In the Church, however, the most abject of women — widows — found themselves at the forefront of great social movements. They were leaders. Some, like Fabiola and Olympias, were among the first founders of hospitals. Others, like Monica and Macrina, were teachers and formators of the intellectual giants of their age.

Still other widows, in fact the majority of them, quietly did the work that keeps the Church moving forward: catechesis, sacramental preparation, and charitable programs.

The history of the Church could be convincingly told as the story of such women. They were refreshingly free of the clericalist mindset that would see their lives as less because they lacked holy orders.

In their poverty, and even in their grief, they lacked nothing because they possessed Christ, and they could fulfill the most heroic ambitions because they did so in Christ.

Knowing the widows of my childhood, I have no trouble believing Christianity’s historical record. Knowing the historical record, I recall the widows of my childhood, and I see no incongruity between the constant black dress and the constant smile. I see perfect consistency between the poverty and the perfectly maintained house.