Rome, Italy, Apr 22, 2017 / 11:52 am (CNA/EWTN News).- The devil’s hatred for Christ and for our redemption is the root cause of all persecution since the beginnings of the Church, Pope Francis said at a special liturgy that focused on modern martyrs.

“The memory of these heroic witnesses, old and new, confirms us in the knowledge that the Church is a Church of martyrs… they have received the grace of confessing Jesus until the end, until death,” the Pope said April 22. He said that if we look well into history, the root cause of every persecution is “the hatred the prince of this world has toward those who have been saved and redeemed by Jesus with his death and with his Resurrection.”

Pointing to Jesus’ words “Do not be afraid! The world will hate you, but know that before you, it hated me,” from the Gospel passage read at the liturgy, Francis said the use of the word “hatred” is both strong and frightening. “He, who is the master of love, who liked so much to speak of love, speaks of hatred,” he said, noting that Jesus “always wanted to call things by their name.”

Jesus has chosen and redeemed us as “a free gift of his love,” he said, adding that through this love, we have been saved from “the power of the world, from the power of the devil, from the power of the prince of this world.” “And the origin of hatred is this: that we are saved by Jesus, and the prince of this world doesn’t want it, he hates us and provokes persecution, which since the time of Jesus and the early Church continues until our days.”

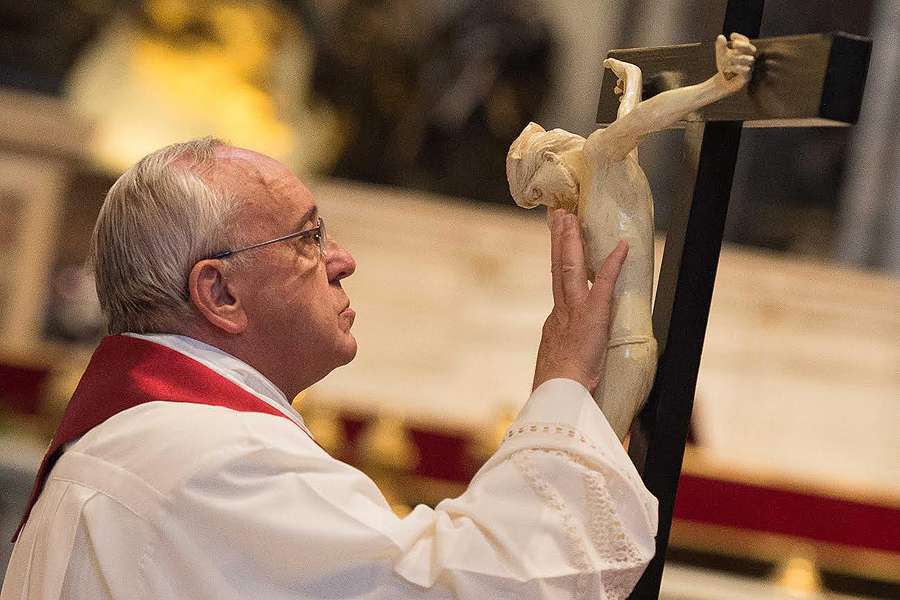

Pope Francis offered his reflections during a special April 22 liturgy honoring the “new martyrs” of the 20th and 21st centuries in the Basilica of St Bartholomew on Rome’s Tiber Island. Overseen by the Community of Sant’Egidio, the basilica was founded at the end of the 10th century and contains a vast number of relics belonging to 20th century martyrs. The collection was initially gathered after the Jubilee of 2000.

A year ahead of the jubilee, Pope John Paul II established the “New Martyrs” commission to study and investigate modern cases of martyrdom in preparation for the event. As a result, the commission gathered some 12,000 dossiers of martyrs and witnesses of the faith from around the world. To commemorate the heroic witness of those who had given their lives for Christ, John Paul II in 2002 had a large icon made and placed in the basilica of St. Bartholomew, which sits on the main altar to this day.

In addition to the icon, various relics and items belonging to the martyrs have been placed in each of the basilica’s side chapels, and are divided by either specific points in history, such as the “new martyrs of Nazism,” or geographical locations, including Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Americas and Europe.

Benedict XVI visited the basilica in April 2008, making Pope Francis the third pontiff to set foot in the basilica, and to keep the papal tradition of honoring new martyrs. In his homily, Pope Francis lamented the fact that “many Christian communities are objects of persecution!” However, he noted that often in difficult moments, people call for “heroes.”

The Church today also needs the heroic witness of martyrs and saints, he said, explaining that this includes “the saints of everyday life,” who move forward with coherency, but also those who “have the courage to accept the grace of being witnesses until the end, until death.”

“All of them are the living blood of the Church. They are the witnesses who carry the Church forward,” he said. By demonstrating with their lives that Jesus is alive and risen, they also “attest with the coherency of their lives and with the strength of the Holy Spirit that they have received this gift.”

Pope Francis then paused for a moment and deviated from his prepared text. He recalled an encounter he had with a Muslim man he met during his 2016 trip to Lesbos who, along with his three children, had fled his village after his wife, who was a Christian, was killed by extremists. When the militants came to their home and asked what their religion was, the woman said she was Christian, and, when she refused to throw down a crucifix she that was hanging on the wall, she was killed in front of her family. This woman, Francis said, is “another crown” that can be added to the rest of the martyrs honored in St. Bartholomew, because “she is looking at us from heaven.”

Pope Francis closed his homily saying the ability to remember the many modern-day martyrs inside a basilica filled with their relics is “a great gift,” because “the living heritage of the martyrs today gives us peace and unity.” “These ones teach us that, with the strength of love, with meekness, one can fight against tyranny, violence and war and can realize peace with patience,” he said, and prayed, asking that each person present might be a worthy witness of the Gospel and the love of God.

Before giving his homily, Pope Francis heard the testimonies of three people who were relatives or friends of modern-day martyrs.

First was Karl Schneider, son of Paul Schneider, a pastor of the Reformed Church who was killed in the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1939 because he defied Nazism as “irreconcilable with the words of the Bible.” In his brief reflection, Schneider said his father had been “strongly opposed every temptation to politically influence the Church.” “All of us, even today, make too many compromises,” he said, “but my father stayed faithful only to the Lord and to the faith. He was a pastor and a spiritual guide. Even in the concentration camp!”

Despite the torture and suffering his he endured, Schneider’s father shouted out from his cell, offering words of comfort and hope from the Bible to the other prisoners. Recalling words spoken by his elderly mother before her death, Schneider said his mother said her husband “was chosen to announce the Gospel and this is my consolation.” As his son, Schneider said he “I feel this consolation until today.”

Next was Roselyne, sister of Fr. Jacques Hamal, the 85-year-old priest who was murdered by two young ISIS sympathizers in Rouen, France in July 2016. Speaking to the congregation, Roselyne said that in his old age Fr. Hamal had been fragile, but “he was also strong. Strong in his faith in Christ, strong in his love for the Gospel and for people, whoever it was, and — I am certain — also for his killers.”

His death, she said, “is in line with the life of a priest, which was one of a life given: a life offered to the Lord, when he said ‘yes’ at the moment of his ordination, a life of service to the Gospel, a life given for the church and her people, above all the poorest. She pointed to the “paradox” that while alive her brother never wanted to be “at the center,” but that after his death, “has given a testimony for the entire world, the greatness of which we cannot measure.”

After her brother died, Roselyne said the reaction of the community was strong. Rather than wanting revenge, there was a desire for “love and forgiveness,” she said, explaining that even Muslims who wanted to show solidarity with Christians came to visit the parish for Sunday Masses in a show of support.

Despite her loss, Roselyne said “it’s a great comfort to see how many new encounters, how much solidarity, how much love have been generated by the witness of Jacques,” and prayed that his sacrifice would “bring fruits, so that the men and women of our time can find the path to living together in peace.”

Finally, a man named Francisco Hernandez gave a brief reflection on his friend William Quijano, killed in El Salvador in 2009 because of his work with youth that sought to promote peace and draw them away from the violence of criminal gangs. In his reflection, Hernandez said the only crime of his friend was that of “dreaming of a world of peace.”

“William never ceased teaching peace, but rather, his commitment has broken the chain of violence,” he said, recalling how Quijano had always insisted that ending violence begins with the youth, and so dedicated himself to working with children. Hernandez said his friend “never spoke of repression or revenge against the gangs, but insisted on the need for a change in mentality.”

“In every existential periphery, William bore witness to his hope in a different world, founding himself on the Gospel and the most human virtues, on the centrality of closeness,” he said, adding: “this is the greatest gift of that the small life of William Alfredo Quijano Zetino, my friend.”