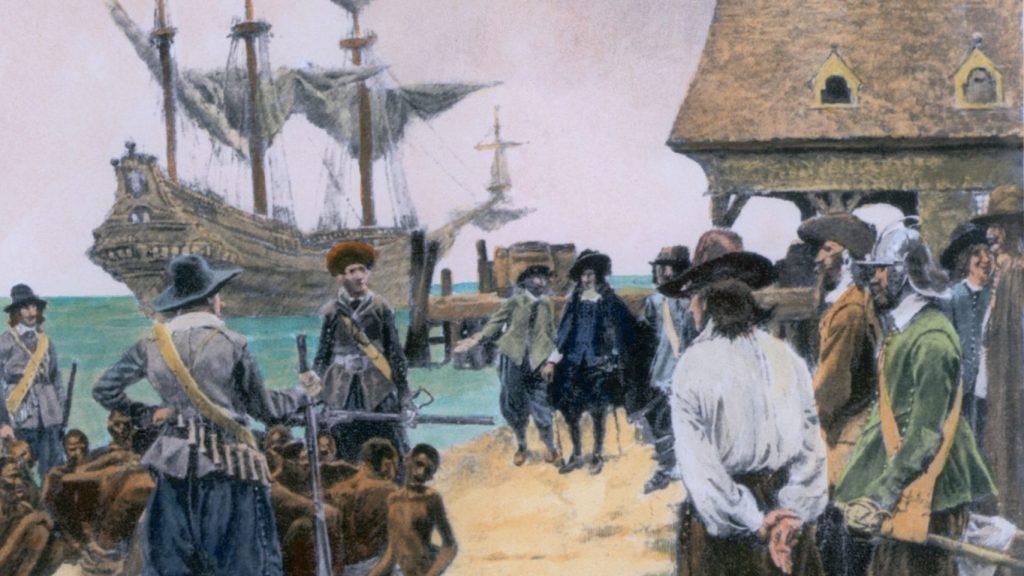

2019 marked the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first black slaves in America. To commemorate, The New York Times earlier this year launched an initiative called the “1619 Project.”

The collection of essays, podcast episodes, and poems seeks “to reframe the country’s history … placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.”

Reframing history is a big job; it certainly has a broader scope than one project can cover. Rather than giving a completely comprehensive understanding of how we should now understand our history, the project challenges us to keep looking for the connections we’ve forgotten — or chosen to ignore — between the past and the present.

How do contemporary movements come about? Sometimes large movements grow from seeds planted long before them. Women’s freedom to write publicly about rape, for example, is a new development in our society, but this freedom did not begin with the #MeToo movement.

Rather, the very history that the “1619 Project” takes on suggests the #MeToo movement is better understood as a spiritual successor to a genre of writing particularly popular in the 19th century: slave narratives written by female former slaves.

In these narratives, women chronicled their time in slavery and their escape and assimilation into free society. Often published by abolitionist presses, many were written not only as autobiography, but also to convince the reader to join the abolitionist cause.

Authors had to walk a fine line, winning cautious, often defensive white readers to their cause without offending them.

This was an especially difficult balance for female authors. With no rights, considered a man’s “property” in the eyes of the law, these women had no way of protecting themselves from the sexual advances of their masters. Sexual assault was a part of almost all their stories.

For women in the 19th century, writing about rape was a delicate subject. Women were not supposed to write about sexual matters; they were supposed to epitomize sexual innocence. Readers were more likely to blame the women than they were to condemn the abuser.

But the fact that this experience was so common inspired some women to dare to write about it, even knowing the effect it could have on their reputations. Harriet Jacobs, a former slave living in the North, wrote her autobiography because she wanted “to kindle a flame of compassion in [the readers’] hearts for my sisters who are still in bondage, suffering as I once suffered.”

Harriet Jacobs’ narrative, “Incidents in the Life of a Slavegirl” (published pseudonymously under the name of Linda Brent), tells her story of escape from a master twice her age who sexually harassed her for years.

Jacobs wrote in a familiar, emotionally direct style that was especially popular among American women. She wanted to stir compassion in her readers, to speak directly to the northern Christian women who would be most likely to be able to help women like her, and also very likely to condemn them. “Woman can whisper her cruel wrongs into the ear of a very dear friend much easier than she can record them for the world to read,” she wrote to abolitionist Amy Post.

Writing her narrative was a gamble: She could face contempt if people discovered who she was.

But she had faith in something even greater than human compassion.

In her narrative, before she informs her readers of her own harassment, Jacobs tells the story of a young slave girl who had been raped by her master and gave birth to his child. The baby died very soon after birth, and the girl was in terrible pain and close to dying, too.

The master’s wife mocked the girl, saying, “You suffer, do you? … I am glad of it. You deserve it all, and more too.”

The mother of the girl, tortured by the words of the mistress, murmured to herself that soon the slave girl would be in heaven.

“Heaven!…” the mistress retorted, “There is no such place for the like of her…”

As the mother wept, the dying girl turned to her and said something very simple, but also very important: “Don’t grieve so, mother; God knows all about it; and he will have mercy upon me.”

Here, even before Jacobs told her readers her own story, she showed them that there is someone greater who already understands what happened to this girl and what happened to her. Even if she, like this girl, is not vindicated by people on earth, even if they hate her and insult her, God knows the whole story, and sees it all with eyes of mercy.

This is a message not only for the women who may judge her, but also for women who had similar experiences. Their stories, she is quietly telling the readers, are with God. Whether they choose to tell them or not, there is one person who knows, and looks upon them with perfect knowledge and compassion. It is groundbreaking writing tucked away in a simple story.

Jacobs’ story conveys something that her critics could not understand and that survivors of abuse sometimes struggle to believe: that a victim’s worth and innocence are not determined by another person’s actions.

Jacobs’ own experience began with her master, Dr. Flint, verbally harassing her. She had been working in his house since the age of 12, and his abuse began when she was 15.

“My master began to whisper foul words in my ear. … He peopled my young mind with unclean images, such as only a vile monster could think of,” she writes. “What he could not find opportunity to say in words he manifested in signs,” and once he realized she could read, he began passing her notes.

When she cried, he would pretend to soothe her, saying that he would take care of her and make her life happy again if she let him. When he got angry and struck her, he blamed her for provoking him.

“Do you know that I have a right to do as I like with you, that I can kill you, if I please?” he said to her.

She desperately wanted to tell her grandmother, whom she looked up to as an example of authentic Christianity (as opposed to the hypocritical Christianity she saw practiced by slave owners). Both of her parents died when she was young, so her grandmother was also a source of motherly love and care.

But Jacobs felt that her grandmother would see her as complicit in the terrible things that were happening to her: “I was very young, and felt shamefaced about telling her such impure things, especially as I knew her to be very strict on such subjects.” She feared that she would be met with anger and judgment when she needed help.

Jacobs kept silent.

One day Flint informed her that he was building a house, removed from the plantation and neighbors, where he expected her to live.

She was terrified. She knew that once she was isolated from society, he would assault her. She felt that she would be better off dead.

And so it happened that another man took advantage of her situation. Sands, a neighbor of her master, heard rumors about Flint’s abuse. He got to know Jacobs and told her he wanted to help. His upper-class status and (seemingly) protective attention seemed very flattering.

Jacobs knew from the beginning that Sands was not looking for mere friendship.

She wanted his protection, and she thought that a relationship with him would save her from being raped by Flint. She was 15 years old, a teenager with everything to lose.

She began a relationship with Sands, and within a few months was pregnant.

Now she would have to tell her grandmother. She dreaded confessing, convinced that she no longer deserved her grandmother’s love.

But she was too late. Mrs. Flint, Jacobs’ mistress, accused her of sleeping with Flint. Her grandmother believed the mistress, and assumed the worst of Jacobs, Flint’s intended victim:

“Has it come to this? I had rather see you dead than to see you as you now are. You are a disgrace to your dead mother … never come to my house again.”

Jacobs loved and greatly admired her grandmother and longed for her forgiveness. Her reaction hurt her deeply: “She did not speak to me; but the tears were running down her furrowed cheeks, and they scorched me like fire.”

Jacobs was heartbroken. She pleaded with her grandmother to listen to her full story. For the first time, she described what had happened to her, how terrified and desperate she had been for so long.

And for the first time, someone had compassion on her: Her grandmother wept with her and recognized her horrible situation. “She did not say, ‘I forgive you;’ ” Jacobs writes, “but she looked at me lovingly, with her eyes full of tears … and murmured, ‘Poor child!’ ”

Eventually, Jacobs escaped to the North. There, she told her story to one of the first Northerners she befriended. Though her honesty was admirable, he told her, he didn’t think she should tell people her story, as “It might give some heartless people a pretext for treating you with contempt.”

Literary critic Elizabeth V. Spelman describes the inclusion of this line as “a spectacular move by [Jacobs],” because, “here she instructs [the readers] about how any decent person would regard her revelations: Only heartless people would have contempt for such honesty, would fail to see that [Jacobs] must provide authentic information if her would-be helpers are really to understand her situation.”

It is a spectacular move. She began her story by reminding her readers of God’s mercy and ended by showing them how to react compassionately to her work. She helped readers to listen and be compassionate.

Jacobs was a talented writer. Her subtlety means that her importance has often been overlooked, but she is an incredibly important woman to think about when reframing history. Because she wrote well before the #MeToo movement, it can be easy to forget that we’re still learning, as a society, how to listen to survivors — but we owe it to Jacobs to continue listening compassionately.