I was in the eighth grade (53 years ago) when I first read about Charles de Foucauld in Henri Daniel-Rops book, “The Heroes of God.” The book deals with 10 men and one woman whom he calls “Adventurers of God,” who “lived … suffered … died to hasten the fulfillment — as much as it is possible for it to be fulfilled on earth — of the wish that every Christian addresses to the Father: “Thy Kingdom Come.”

Daniel-Rops had what they call in Spanish “buena puntería” (“good aim”). Three of the five non-saint heroes who were not canonized (nor beatified) at the time he wrote the book have since been raised to the altars: St. Junípero Serra, St. Damian of Molokai, and now, Bl. Charles de Foucauld, whose canonization date has yet to be announced.

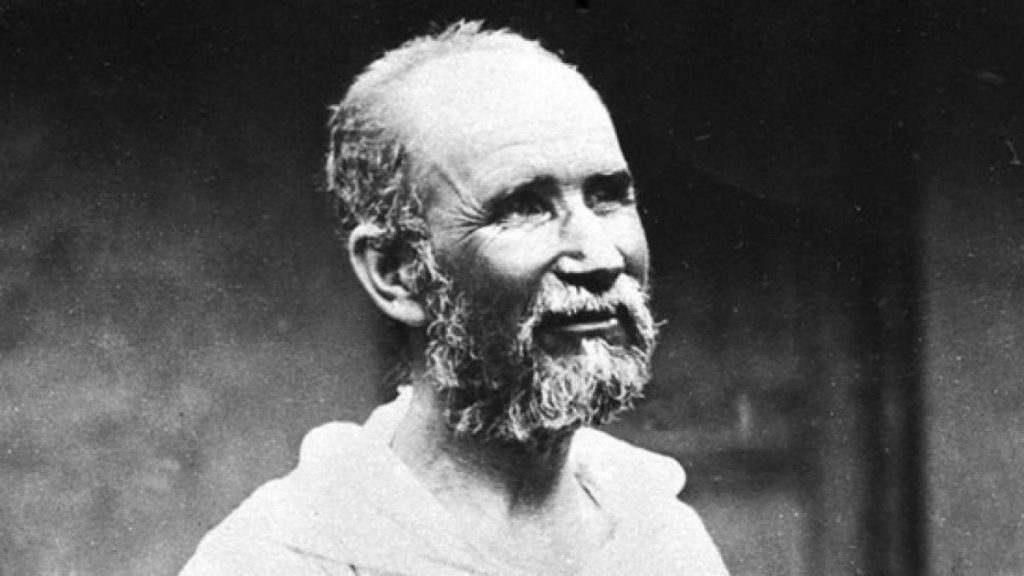

Perhaps of all the heroes in the book, Viscount Charles de Foucauld had the strangest life story. He was born in Strasbourg, France, into a family that had historic ties to St. Joan of Arc and St. Louis, as well as some relatives who died for the faith in the French Revolution.

And yet, his path to heaven had many twists and turns. His mother was a devout Catholic, but she died when de Foucauld was 8 years old, a few months before the death of his father. He was raised by his maternal grandfather, who was very indulgent to the boy and his sister.

That indulgence became a weakness because the boy became a man who was extremely self-willed, even within the French Army, where he became a very wealthy and, as Daniel-Rops writes, a “boastful, lazy and dissipated second lieutenant.” He lost his faith when he was a teenager and lost his grandfather soon after — but not before he had been given an ample inheritance.

They say in Alcoholics Anonymous that your strengths are your weaknesses — and vice versa. I think de Foucauld was a good example of that. He was self-indulgent to an extreme, famous for ordering catered foie gras and the finest wines when he was in cavalry school and earning the name “le porc” (“the pig”) from his fellow students. One of his cousins remembered that chubby Charles was the terror of the dessert table at family parties.

But this young man, extremely intelligent but so lazy he got poor grades, was converted by the strangest of the Lord’s devices. Posted to the Sahara, and getting in trouble constantly for scandalous behavior, de Foucauld fell in love with Northern Africa when fighting a rebellion in the French colony of Algeria.

He explored Morocco incognito, disguised as a Jewish rabbi, and wrote and published a report that won him prizes and made him well known among geographers in France. Contact with Judaism and Islam in his travels marked him for life, however.

After a time in Paris, he went back to serve in Africa. Then came disillusion with the army because of political issues. God had him where he wanted him. He later marveled how God used “unexpected solitude, emotion, illnesses of dear ones, deep and intense feelings, and a [sudden] return to Paris in the wake of a surprising event.”

Through the prayers, example and prodding of a beloved cousin, Marie de Bondy, de Foucauld was converted back to the faith. His cousin arranged an encounter with Father Henri Huvelin in St. Augustine Church in Paris. De Foucauld went for a “discussion” of his lack of belief and Father Huvelin said to him, “Kneel down and confess your sins.”

“But I have no faith,” the “penitent” responded.

The priest only responded: “Confess!” And he did.

Then Father Huvelin said, “Have you eaten breakfast?” He had not. “Then go into church immediately, Mass is starting, and take communion.” That is how de Foucauld made what he called his “second first communion.”

His exotic pilgrimage continued. The heraldic motto of his aristocratic family was “jamais arrière” (“never retreat”), and so it was with de Foucauld’s search for what God wanted from him. The same lack of satisfaction that had driven his expensive and often immoral lifestyle was evident in the extreme choices of his religious vocation.

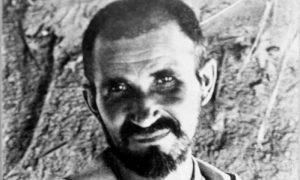

He was never satisfied with the sacrifices he made for Christ. The ex-soldier entered a Trappist monastery of Notre Dame des Neiges. Seeking still greater asceticism, he transferred to another monastery, this one in Syria at Akbes.

His soul was not at rest in Syria. He wanted to live the hidden life of Jesus in Nazareth. He found work at a Poor Clare convent in Nazareth itself, becoming the gardener for the nuns and spending hours in prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. Still, he was not at peace. He returned to France, studied for the priesthood, and was ordained. Then he decided to return to Africa as a chaplain to the French soldiers.

I say “as a chaplain,” but it was not that simple. He desired to be a hermit like the Egyptian Fathers of the Desert. By a life of prayer and fraternity in a hermitage in Beni-Abbes, he would give witness to the Muslims and evangelize silently, preaching only with his presence and his charity. He had dreams of founding a religious order, “The Little Brothers of the Sacred Heart.”

But Beni-Abbes was not enough. A friend suggested an even more remote and poor site, Tamanrasset, where he could get to know the Tuareg tribesmen. He built a hermitage there and began his study of the Tuareg language, his translation of the Gospels in that language and the scholarly work of compiling a bilingual dictionary and a grammar book, then a collection of indigenous poetry that would later be published.

His gift of tongues was formidable, but also his charism to inspire even the Muslims with respect for his vocation. They began to call him their “marabout” (“holy man”). He believed that the prayer of adoration would be the groundwork for evangelization in the desert.

When World War I broke out, some tribes declared a jihad against the French. Father de Foucauld was convinced by the military to move from his hermitage to a small fort, where he lived alone but could give shelter to the other villagers in the case of an attack. There he was killed by a party sent to kidnap him on Dec. 1, 1916.

He never got anyone to join his proposed religious community. Nor did he ever convert anyone in the village to Christianity. Although he is well known now as a writer of meditations and reflections, he never saw any of his religious writings published in his lifetime. His “project” had failed.

Thankfully, holy failures are often the seeds of success. After his death, Father de Foucauld found disciples. A biography by René Bazin in 1921 brought attention to the desert hermit’s life and vast writings, and eventually many of these were published.

A seminarian by the name of René Voillaume read the biography and was inspired. He eventually founded the community of the Little Brothers of the Sacred Heart and then the Little Brothers of the Gospel. Women disciples founded the Little Sisters of the Sacred Heart and the Little Sisters of the Gospel, a group I got to know in El Salvador.

Mother Teresa of Calcutta once said that God does not call us to be successful, but to be faithful. I would add that faithfulness brings spiritual success. The Church needs more failures like Bl. Charles de Foucauld so that maybe we can all be more faithful.