It’s easy to fall into nostalgia, and a Catholic can be as prone to it as anyone. We forget that past ages had as many miseries as our own.

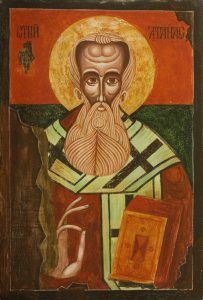

Today, when we look back at the fourth century, we call it the Golden Age of Doctrine. The Church fielded a team of all-time greats, the theologians cited as authorities in textbooks ever afterward: St. Athanasius, St. Basil, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Ambrose, St. Jerome, St. Augustine, St. Chrysostom. Seven of the original eight doctors of the Church were writing during the fourth century.

Theirs are the books that have survived. We read them and we think it must have been bliss to be alive in those days.

But it wasn’t. St. Athanasius was exiled five times for his beliefs. Basil battled constantly against hostile leaders in church and state. Church politics drove St. Gregory of Nazianzus into profound depression. And St. Jerome noted that “the whole world” was suddenly dominated by the Arian heresy.

If you walked into a church during the Golden Age, you were as likely to get bad doctrine as good.

The Emperor Constantius once mocked St. Athanasius for standing absolutely alone in his defense of the Nicene Creed. The battle seemed to be “Athanasius against the world.”

That’s an exaggeration, of course. The truth was that the situation was volatile, and the people were polarized.

The crisis began in the year A.D. 318. Three centuries of persecution had finally come to an end. For the first time in history, Christians were free to practice their faith. Then, rather suddenly, the meaning of that faith was called into question by a priest in Alexandria, Egypt.

His name was Arius, and he believed that Jesus was not divine in the way God the Father was divine. He preached that the Son was a creature, neither coeternal nor coequal with the Father. A genius at communication, Arius packed his doctrine into catchy hymns and slogans. He was also adept at networking, and he cultivated friendships with influential people in government.

His ideas spread by every means, and converted many to his cause. Many, but not all, and those who declared their fidelity to the eternal triune God, were dogged in their loyalty. Thus churches were divided in two, and factions warred with factions over who had rights to the parish property. In many places the dispute erupted in violence.

This was not a mere difference of opinion. It was threatening to divide the empire. The Emperor Constantine had labored long years for the unification of his territory and the legalization of Christianity. Now the Church seemed to be at war within itself — and was dragging the entire empire into the conflagration.

In A.D. 325, the emperor summoned a meeting of bishops to settle the matter definitively. In fact, Constantine himself attended the Council of Nicaea and suggested the language that (he thought) would resolve the dispute. The bishops accepted his proposal. They imposed an anti-Arian creed.

And that settled nothing.

Some people opposed the Nicene Creed because they were Arians. But others thought it was impious to speak about the Trinity at all, except in the exact words that appeared in Scripture. And still others thought the terms suggested at Nicaea were misleading — that they actually overcorrected Arius and landed in a different heresy.

Far from settling anything, the council had actually stirred the pot. New voices rose from every city. Some proposed a language of compromise that might accommodate both sides of the debate. Soon there were more parties and factions than could be counted (or easily pronounced): Homoiousians, Homoians, Anomoeans, Apollinarians, Macedonians. Each had its shade of verbal difference and guarded it with passionate intensity.

St. Athanasius did seem often to stand alone against the lot of them. He wasn’t there for the dialogue. If you weren’t with him, you were against him, and he tended to label all opposition as “Arian” — even the opponents who also opposed Arius.

Through his long lifetime, he was steadfast and dogged. At his death, the world wondered how the argument would go forward. Who would take up the defense of Nicaea?

The man often called “The Athanasius of the West” is St. Hilary of “Pictavium” (“Poitiers” in modern France).

Raised in the old Roman religion, St. Hilary converted to Christianity as a young adult. He was a married man with a young daughter; but it seems that the whole family decided to commit their lives entirely to God. All three were active in the life of the Church. St. Hilary proved to be an effective teacher of the Nicene faith. When the office of bishop became vacant, the local people of Poitiers unanimously chose him.

He was like St. Athanasius in many ways. He championed the faith of the Council of Nicaea. He opposed Arianism and stood up to the Emperor Constantius. And he suffered exile for all this.

But St. Hilary’s methods and his virtues were very much his own — and they were quite distinct from those of his Egyptian colleague.

Far more than St. Athanasius, he was willing to engage the legitimate concerns of those who were uneasy with the Nicene doctrine.

He also strove to communicate in language that might persuade his opponents, and he was careful to avoid terms that might inflame or alienate them. When he wrote of the Trinity, for example, he avoided metaphors and images and confined himself to evidence from both Testaments of Sacred Scripture. All analogies failed when applied to the divine mysteries. But Scripture stood as the universally accepted record of God’s self-revelation.

When St. Hilary spoke of God, he strove for a dispassionate sobriety in his language. He preferred the “soundness of heavenly words” to “violent and headstrong preaching.”

During his exile, he traveled extensively. He brushed up on his Greek and read the works of theologians in the East. He met with theologians from various parties in the current disputes. And he genuinely tried to understand them.

While he was living in Phrygia, he attended whatever local councils he could. The Eastern bishops recognized his brilliance and his goodwill, and they allowed him to participate fully, even though his own diocese was very far away.

St. Hilary was a brilliant builder of consensus. He was willing to work with people whose views were fundamentally different from his own. He strove to discern a common purpose and then make a common cause. He even collaborated with Arian bishops in common opposition to heresies that were far more radical.

In all of this he maintained his integrity. And, as friendly as he was, he never accommodated his language, as some bishops did, in order to give equal cover to Nicene orthodoxy and Arian heresy.

With clear teaching and merciful action, he was able to build a coalition and lay a solid foundation for Nicene orthodoxy in the West.

The idea of a Golden Age is largely illusory. The fourth century was a muddle of confused theologizing. Yet the confusion itself made possible a profound development of the faith, because of great teachers. Yes, we can learn from St. Athanasius in his courage and precision. But let us also learn from St. Hilary in the ways he brought about peace and consensus without compromising the truth.