Saints are always more complex than their holy cards can convey. But we need to reduce them to categories we can comprehend, so we bring them into tight focus.

We find a title for the part of their life we consider most important: martyr, stigmatist, virgin, mystic, theologian, confessor, wonderworker, scholar. In art the saints are often depicted with a symbol of their outstanding trait, their singular excellence.

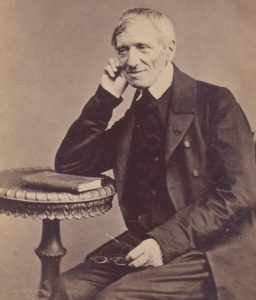

But the Church’s newest saint, John Henry Newman, defies such simplification. He excelled in so many fields that it is impossible to choose just one.

To examine the breadth of Newman’s contributions, Angelus News interviewed several scholars who specialize in the study of Newman’s work.

Ryan Marr is executive director of the National Institute for Newman Studies, based in Pittsburgh, and author of the book “To Be Perfect Is to Have Changed Often: The Development of John Henry Newman’s Ecclesiological Outlook, 1845-1877.”

Dwight Lindley is associate professor of literature at Hillsdale College in Michigan.

Father Juan Velez is author of “Holiness in a Secular Age: The Witness of Cardinal Newman” and the biography “Passion for Truth: The Life of John Henry Newman.”

THEOLOGY

Newman often insisted that he was not a theologian. “What he meant by that,” says Lindley, “was that he was not a systematic thinker in the mode common to Catholic theologians of the late 19th century.”

His lifetime coincided with the flourishing of the manualists, theologians whose textbooks presented dogma in a rigorous logical framework. Newman valued their work, but saw his task as essentially different.

Newman, says Lindley, “did theology when specific circumstances required it of him: If a friend faced religious doubts, Newman began to think about the nature of faith; if the Church's authority was publicly challenged, he would work up an account of that authority’s grounding. Thus, he had a more rhetorical approach, like the early Fathers of the Church.”

In taking a different tack, however, Newman inadvertently set new standards for the practice of theology. His books were fresh and startling. And because they focused on real contemporary concerns, they gained attention, and even international celebrity, for their author.

“Newman was arguably the greatest English-speaking theologian of the 19th century,” says Marr.

Marr identifies Newman’s greatest contribution as “his theory of doctrinal development.”

Before Newman, he explains, “most Catholic theologians operated with a successionist understanding of Christian history, in which Christ was understood to have handed a deposit of faith to the apostles, and then the Church transmitted these propositional truths down through history.

In contrast, Newman described the history of doctrine in more organic, developmental terms, theorizing that the Church gained a deeper understanding of the truths of the Faith through ongoing reflection.”

Newman’s account, Marr concludes, “has become the standard Catholic position on the topic. Even those theologians who quibble with details of Newman’s theory must take his treatment as their starting point.”

Newman is also famous for his ideas about the “sense of the faithful” (commonly known as “sensus fidei” in Latin) and the role of the laity in the Church’s life.

Marr explains: “In brief, Newman argued that the devotion of the faithful is one of the sources of tradition, and that the bishops therefore have a responsibility to consult the faithful in the process of doctrinal discernment.

“This is another one of Newman’s ideas, perceived as radical in his own day, that has moved to the center of official teaching and is now understood to be foundational.”

EDUCATION

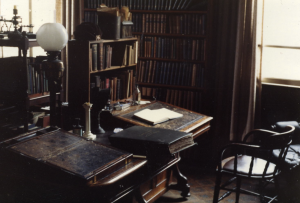

Newman was himself an educator, who taught at Oxford and helped establish a Catholic university in Dublin, Ireland, and later a high school in Birmingham, England.

It was the Dublin project, in the 1850s, that led to the publication of his book “The Idea of a University.” There he presented a holistic vision of higher education. According to Lindley, Newman “set forth the ideal of a circle of sciences, each interrelated with the others, coming together to form a whole view of reality.

“This was to be the object of study in a liberal education, and Newman’s vision still guides liberal arts programs all over the world, even if many of them have less and less clarity about what ‘the whole’ is or how the disciplines should relate.”

Like Lindley, Marr considers Newman’s “Idea of a University” to be “a classic in educational theory.”

“Newman’s essay,” he says, “is a stirring manifesto for preserving the liberal arts that stands in stark contrast to the reductive and profit-driven approaches that drive so much of contemporary higher education.”

If it is considered a classic, however, it is today mostly honored in the breach, says Velez.

“His educational philosophy is acclaimed and respected,” says Velez, “even if it is unfortunately considered idealistic.”

Nevertheless, “The Idea” remains a touchstone for any discussion of educational reform.

PHILOSOPHY

Though he was not a philosopher by training, Newman managed to break new ground in epistemology, the branch of philosophy that investigates the nature, grounds, and limits of human knowledge.

He had, says Lindley, a “fresh approach to the question of faith and reason.”

“He presented a view of reason as always relying on what we might call ‘natural faith’: that is, every act of reason — every explicit effort at making sense of something, or accounting for something — is only possible because of a vast number of conclusions we have already reached implicitly, under the surface.

“Newman’s turn to the implicit, or tacit, dimension of reasoning paved the way for thinkers such as Michael Polanyi and many others in the 20th century.”

Newman worked out these ideas in his book “A Grammar of Assent,” which Marr describes as “his most difficult” work.

“Newman posits that there are different types of reasoning that are appropriate to different fields of inquiry,” Marr continues. “The scientific method is powerful and provides us with a breadth of useful knowledge, but it does not give us access to all that we can know about the world. As a really basic example, you would not use the scientific method to discover whether or not your mother loves you.

“For Newman, there are truths that we take as basic even though we have never proven them. Another illustration he uses is the way that English citizens assume that they live on an island. Only a very few have taken the time to circumnavigate the entire island (remember, this is pre-satellites and Google Maps), yet all of them live with the certain knowledge that their homeland is surrounded by water.”

Marr sums up Newman’s application of the principle to matters of faith: “When it comes to the beliefs that are most important to us, such as belief in God, it would be impractical, even foolish, to think that we have to provide detailed proofs in support of those positions.”

HISTORY

“In history,” says Father Velez,” Newman “revived the studies of the Church Fathers.” Newman translated major works of the early Church, and applied his genius to the minute analysis of that period. He considered the Fathers to be witnesses to the authentic interpretation of Scripture.

Newman’s use of historical evidence had a profound impact on theology and related fields.

Marr explains: “Newman’s theory of development helped to make Christian thinkers in general more historically conscious. Before that time, the standard apologetic was to present the deposit of faith as a set of propositions transmitted from Christ to the apostles and down through history.

“Newman showed that the process was more dynamic than that, though without ever casting doubt on the objectivity of the Church.”

According to Lindley, Newman’s methods have been useful even beyond the confines of Church history. His work “suggests not only a way of interpreting the evolution of Church teaching over time, but a hermeneutic for understanding any tradition of thought over time.

“Any organized tradition of thought,” Lindley adds, “will have its own principles, teleology, and developmental arc which can be traced, and therefore a kind of intelligibility … Newman pioneered a philosophy of history that would become much more prominent in the 20th century. Alasdair MacIntyre, for example, has cited Newman as a chief influence on his theory of the rationality of traditions.”

LITERATURE

The great novelist Samuel Butler ranked Newman, along with Robert Louis Stevenson, as “one of the greatest masters of English style.”

Newman was a prolific poet, and he wrote two bestselling novels, “Callista: A Tale of the Third Century” and “Loss and Gain,” the story of an Oxford student’s conversion to Catholicism.

“His novels are still worth reading, particularly if one is interested in Victorian-era literature. I personally prefer “Loss and Gain” to “Callista,” says Marr. The former provides an inside glimpse into the religious climate of Oxford University during the middle part of the 19th century.

DEVOTION

In Newman’s time, Catholicism was marginal in English society. Until 1829, the law imposed severe restrictions on participation of Roman Catholics in public life and government. Catholics were treated as potential traitors, since they did not follow the state religion.

Because of these (and other) restrictions, however, Catholics often experienced their own faith as something imported from continental Europe, by way of foreign missionaries and overseas publishers.

Newman was an inspiring and popular preacher, and he showed English Catholics a spiritual expression that was distinctively theirs. “Newman's approach to devotion,” says Lindley, “was simpler and more practical than much Catholic devotional literature of the time, partially because he was English and a former Protestant.”

Newman’s style appealed immediately to Catholics everywhere in the English-speaking world. In the 1850s his books, hot off the press, were serialized on the front page of diocesan newspapers in the United States. He was similarly received among Catholics in Australia.

Because of Newman’s background, he remained sensitive all his life to the concerns of Protestants. He spoke of Catholicism in a way they could understand and, sometimes, accept, and by his example, he taught other Catholics to speak the same way.

With Newman’s canonization, the Church proposes his life as one worthy of imitation and veneration. He is a model of prayer for all ages, not just his own. “Newman had a deep and intense prayer life. This gave his devotional writings a real power, because it was clear that he was drawing from his own rich spiritual experience,” says Marr.

And he composed hymns that the Church still sings with gusto.

Lead, Kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom

Lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home—

Lead Thou me on!