A couple of years ago — when there were Catholic conferences attended by many people — I volunteered to man the book table at one in my city. It was a wonderful event, attended by hundreds. And the organizers made sure that priests were available for confession throughout the day.

My table was the last, nearest to a conference room that had been repurposed as a confessional.

Well, soon after the conference began, a woman came out of the room, and she stopped at my table.

She leaned in as if she had a secret. She said, “There are no lines right now. You can go right into confession!”

I thanked her. Then I saw her go to the next table and repeat the big secret: “There are no lines. …”

And then she went to the next table. And the next.

By the time she got to the end, there was a line.

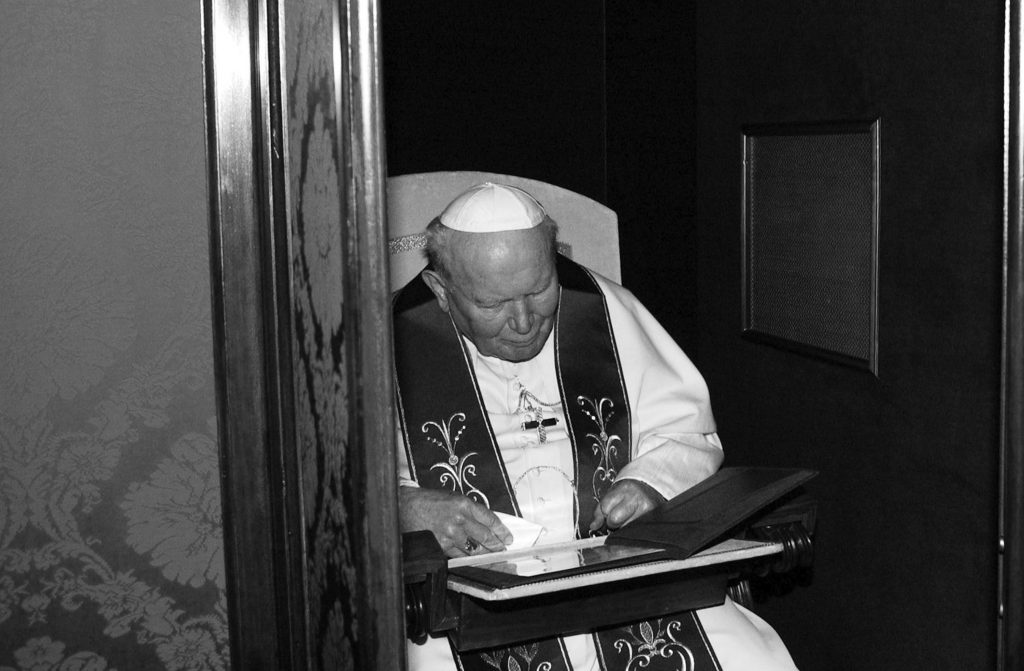

St. Pope John Paul would have approved.

He loved the sacrament of confession. He loved it as a penitent. He loved it as a confessor.

As a penitent he loved it by going frequently. He went at least once a week, his secretary, Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz recounted. “He would also confess before major feast days and special liturgical seasons.”

As a priest, he knew that the confessional was important to his life and ministry. He said, “It is in the confessional that [a priest’s] spiritual fatherhood is realized in the fullest way. It is in the confessional that every priest becomes aware of the great miracles which divine mercy works in souls which receive the grace of conversion.”

We can trace Pope John Paul’s love for confession to a special grace he received when he was young.

It happened in 1947, less than a year after his priestly ordination.

His bishop, Cardinal Adam Sapieha, assigned him to pursue studies in Rome, and gave him extra money for travel in Europe. So, before classes started, Father Wojtyła (as he was then known) made a pilgrimage to France and stopped in the town of Ars, where St. John Vianney had served as parish priest in the 19th century.

There he saw the small confessional where the Curé of Ars would sit sometimes for 18 hours a day. He heard the story of the tens of thousands who traveled to the rural parish to confess their sins — 80,000 came in the year 1858 alone. Trains had to accommodate the priest’s popularity by adding a stop in the middle of nowhere. The local government had to build a new station to accommodate the trains.

The young priest was so deeply moved that he resolved to be like St. John Vianney. He would make himself a “prisoner of the confessional,” always available to penitents. And he would awaken in his congregations a strong desire for the graces available in the sacrament.

In less than two years Father Wojtyła received his first parish assignment back in the Archdiocese of Kraków, and he made good on his resolution.

His biographer George Weigel said that Father Wojtyła “was, by the testimony of his penitents, a ‘fantastic confessor.’ ” Confession with Father Wojtyła “could last as long as an hour, sometimes even longer.”

Father Wojtyła came across not as a judge but rather a guide and friend. This ran contrary to his training. In seminary, he had been schooled in manuals that were juridical in their approach and deliberately positioned the priest-confessor as a judge.

But he concentrated on the human person rather than the transgression. He was attentive and prayerfully involved in the sacrament.

He was, Weigel said, “a demanding confessor but in a very different way.”

“The goal was to deepen one’s Christian conviction and insight, not simply to internalize a checklist of moral prohibitions. The rules were there; they were real; they were to be obeyed. But the rules were not arbitrary. They defined the drama because they illuminated the dramatic tension in life, the tension between the person-I-am and the person-I-ought-to-be. The confessor was to be a counselor in the practice of the virtues.”

Unfortunately for his congregation, Father Wojtyła did not remain a parish priest for long. Pope Pius XII appointed him an auxiliary bishop at a very young age — only 38. And four years later Pope John XXIII named him Archbishop of Kraków.

Even as archbishop, however, he continued his personal practice of frequent confession. Once (or more often) every week Archbishop Wojtyła would walk to the nearby Franciscan church and stand in line. He would hear confessions, too, when he had the chance — but the demands of his office permanently dashed his youthful plans to be a “prisoner of the confessional.”

Nonetheless, he often reminded his people of the mercy available in the sacrament. And he reminded his priests of their obligation to accompany people as ministers of the sacrament.

In his archdiocesan plan for the implementation of the Second Vatican Council, he quoted the council’s decree on the ministry and life of priests, saying that priests “are united with the intention and the charity of Christ when … they show themselves always available to administer the sacrament of penance whenever it is reasonably requested by the faithful.”

It was during his years as pope, however, that his reflections on the sacrament came to full maturity.

In his first encyclical letter, “Redemptor Hominis” (“The Redeemer of Man”), he linked confession inseparably with Communion.

“The Eucharist and Penance thus become in a sense two closely connected dimensions of authentic life in accordance with the spirit of the Gospel, of truly Christian life. The Christ who calls to the Eucharistic banquet is always the same Christ who exhorts us to penance and repeats his ‘Repent’.”

It is a theme as old as St. Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians. But he saw that the Church of his time was in need of a reminder.

He noted that the 1960s had revived an awareness of the communal effects of sin — and the need for reconciliation with the community. Nevertheless, he emphasized that sin is first and foremost an offense against God.

“Conversion,” the new pope said, “is a particularly profound inward act in which the individual cannot be replaced by others and cannot make the community be a substitute for him.”

So, again, he saw confession as integral to the drama of each Christian life.

He spoke of the sacrament not so much as a duty of the faithful, but a right: “In faithfully observing the centuries-old practice of the Sacrament of Penance … the Church is … defending the human soul’s individual right: man’s right to a more personal encounter with the crucified forgiving Christ.”

This was certainly a fresh approach — Confession as a right that is not to be denied to God’s people.

But that’s not his most startling point. He also defended the sacrament as a right that belongs to Jesus. He said, “This is also a right on Christ’s part with regard to every human being redeemed by him: his right to meet each one of us in that key moment in the soul’s life constituted by the moment of conversion and forgiveness.”

So, in preaching about confession — and in making confession accessible — the Church is doing more than dispensing justice. It is enabling love.

In his next encyclical, “Dives in Misericordia” (“Rich in Mercy”), these themes came even more to the forefront. Once again, he emphasized the connection between Eucharist and confession, which are the only sacraments a Catholic can receive frequently. Pope John Paul urged Catholics to take up a “conscious and mature participation” in both. In the Eucharist, he said, Christ comes “to meet every human heart.” But it is confession “that prepares the way for each individual, even those weighed down with great faults.”

The pope arranged for the 1983 Synod of Bishops to address questions of “Penance and Reconciliation in the Mission of the Church.” The following year he devoted his apostolic exhortation, “Reconciliatio et Paenitentia” (“Reconciliation and Penance”), to the findings of the synod.

Then, in 1986 on Holy Thursday, he published a letter to all the priests of the world; and in it he recounted what he had learned in his 1947 pilgrimage to France.

He told the story of St. John Vianney, and he urged all priests to imitate the holy Curé in making themselves available for confession.

But he also spoke with sadness about the decline in the practice of confession. He declared that there was an “urgent need to develop a whole pastoral strategy of the Sacrament of Reconciliation.”

“This will be done,” he said, “by constantly reminding Christians of the need to have a real relationship with God, the need to have a sense of sin when one is closed to God and to others, the need to be converted and through the Church to receive forgiveness as a free gift of God.”

The matter would remain urgent for him to the end of his days. To the U.S. hierarchy he spoke of the problem as a “crisis,” which had become “a challenge to the Church’s fidelity.”

At stake, he said, “is the whole question of the personal relationship that Christ wills to have with each penitent and which the Church must unceasingly defend.”

Many years have passed since he made those pleas; and the crisis remains. A 2008 study conducted by Georgetown University’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate concluded, “Three-quarters of Catholics report that they never participate in the sacrament … or that they do so less than once a year.” Only 12% go once a year. Only 2% go once a month or more.

What the situation requires of us — especially the laity — is a commitment to an active apostolate. We need to be like that lady at the conference. We need to go to confession — and then go to our family members, co-workers, and neighbors, saying, “There are no lines. You can go right in!”

So many people are out there hurting and wounded — and we’re standing around with a pocketful of medicine that can heal them.

It doesn’t work for us to say, “Hey, you look like a sinner. Maybe you ought to try confession.” But we can surely speak from our own experience. We can tell them why we go. We can tell them about our own healing.

Pope John Paul wasn’t afraid to let the world know he went to confession every week. He wasn’t afraid to invite others to join him in the practice of frequent confession.

We can do this, too.

If it’s been a while . . .

If you haven’t darkened the doorway of the confessional in years, don’t worry. Our Faith is big on welcoming prodigal children home. But don’t delay any longer. Just go. You might even want to make an appointment with your parish priest, so you can spend a little more time, without worrying about holding up the line.

And let Father know at the start that it’s been a while, and that maybe you’re not sure how to proceed. Also, if you’re nervous, say so. The point of the sacrament is mercy; and the more the priest can dispense in the name of God, the merrier the occasion should be.

Four Cs for a good confession

- BE COMPLETE. Don’t leave any serious sins out. Start with the one that’s toughest to say.

- BE CLEAR. Try not to be subtle or euphemistic. Father should understand what sin you’re confessing.

- BE CONTRITE. Remember, it’s God you’ve offended, his forgiveness you seek.

- BE CONCISE. No need to go into detail. Often when we do, we’re just trying to make excuses for our behavior. There may be people in line behind you. Don’t make them wait!