Catholics today know St. Michael the Archangel primarily from one short prayer, which some parishes recite at the end of Mass.

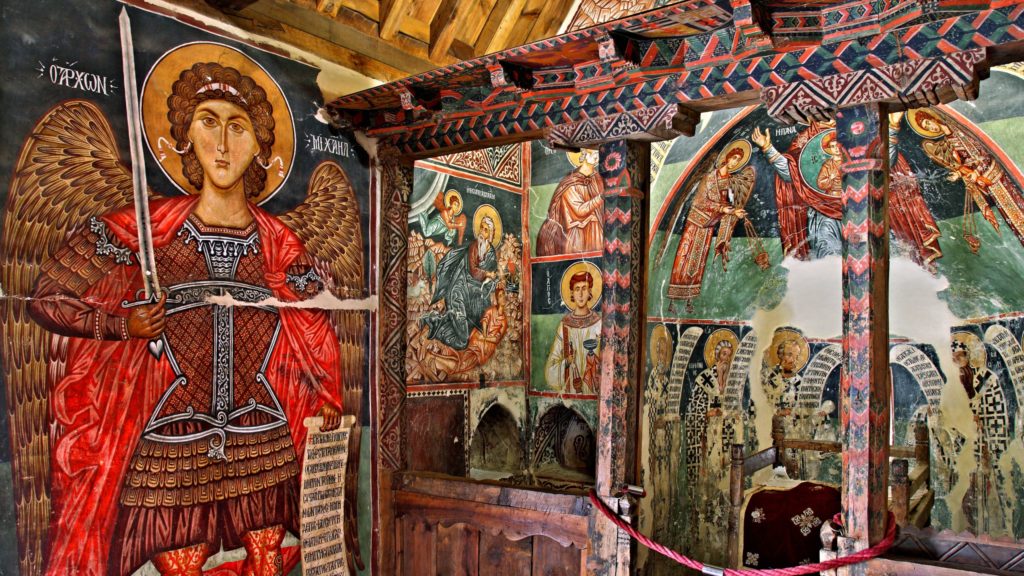

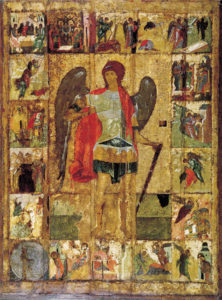

For our spiritual ancestors, however, Michael loomed larger. The rabbis of ancient Judaism, the Copts of ancient Egypt, the popes of ancient Rome, and the great martyrs of the early Church all held Michael — whose feast day Roman Catholics celebrate Sept. 29 — in special esteem. A heavenly prince, he stood, for the ancients, at the center of many earthly mysteries.

Michael is everywhere in the Bible

The Jewish folklorist Louis Ginzburg documented the ancient traditions regarding Michael. In the Hebrew Bible, Michael is mentioned by name only three times, all in the Book of the Prophet Daniel (10:13, 10:21, and 12:1). But for the rabbis of early Judaism he lurked in many books, working anonymously or hiding between the lines.

He was there from the first moment of creation, say the rabbis, proving himself faithful when the angels underwent their test. Shown the figure of Adam as the “image of God” (Genesis 1:26–27), Michael bowed down in worship, while Satan refused and rebelled.

And Michael did not abandon the first man at the time of the original sin. Rather, he stayed and taught Adam the skills of agriculture and blacksmithing. In time he also taught Cain the methods of farming, so that the exiled man could support his family.

Afterward he remained active in the lives of those who were chosen by God. Certainly he was always with Abraham. It was Michael, we’re told, who informed Sarah that she would bear a son.

It was Michael who rescued Lot at the destruction of Sodom.

And it was Michael who stayed the hand of Abraham when he was about to sacrifice his son Isaac. It was Michael who produced a ram to take Isaac’s place.

According to the rabbis, it was Michael who wrestled with Jacob and then blessed him — and the only reason the angel ended the wrestling match was because he had to hustle back to heaven for morning prayers.

The story goes on as Israel was taken captive in Egypt. Michael, we learn, was the fire that flamed from the burning bush as Moses approached it.

Michael was the pillar of fire that led Israel by night — and he was the pillar of cloud that directed them by day.

And it was Michael, once again, who instructed Moses on Mount Sinai — Michael who filled the tabernacle and temple with the glory cloud, which was the sign of God’s presence.

The rabbis tell us also that Michael destroyed the Assyrian army and prevented them from entering Jerusalem.

He would have protected Israel from Nebuchadnezzar as well, but by then the sins of Israel were too great. The rabbinic accounts have Michael bargaining with God the way Abraham had made a plea for the people of Sodom. But God would not relent. And so the people were taken away as captives.

Still, even while the Jews were in captivity, Michael continued to press his case. He was active, we’re told, during the persecution in the time of Esther, and “the more Haman accused Israel on earth, the more Michael defended Israel in heaven.”

Michael was always there for the Chosen People. He is mentioned 10 times in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The sect that produced the scrolls were expecting a great war, and they knew that Michael would appear as their deliverer. In their War Scroll they pray, “Today is [God’s] appointed time to subdue and humiliate the prince of the realm of wickedness. God will send eternal support to the company of his redeemed by the power of the majestic angel … Michael.”

According to the Jews in the time of Jesus, Michael was everywhere he was needed.

Michael delivers the martyrs

The early Christians had the same strong sense of Michael’s ubiquity and power. As he had been the guardian of Israel, he was now guardian of the Church.

Through brutal persecutions during the reigns of the Roman emperors Decius and Diocletian, Christians cultivated the habit of invoking Michael in times of danger. This was especially true of the Coptic believers in Egypt.

In the accounts of the martyrs we sometimes see Michael delivering them from torture — and other times delivering their souls to heaven.

The Copts were (and remain) so devoted to Michael that they established 12 feasts in his honor, one per month, to be observed every year. The feasts commemorate the great events in the archangel’s life, from his first appearance to Abraham to his deliverance of a Christian emperor in battle.

The monuments line up

In the West, Michael was similarly honored. When plague ravaged Rome at the end of the sixth century, St. Gregory the Great reportedly had a vision of Michael atop an ancient building, and the angel was sheathing his sword, and the pandemic came to an end at that moment.

And even today the building where he appeared bears testimony. It’s called Castel Sant’Angelo, the Castle of the Holy Angel.

Devotion to Michael continued into the Middle Ages, as many of the great monasteries in Europe were named for him. In modern times, geographers have noted that 12 major shrines to Michael appear on the world map — and they compose a straight line stretching from Ireland to Israel. (Is there an echo here of the 12 feasts of Michael on the Coptic calendar?)

Among those shrines is the beautiful Mont St. Michel in Normandy, France.

There is no way medieval monks could have plotted that linear course over hundreds of years and thousands of miles.

A modern revival?

In times of trial, the ancients knew the archangel to be a patron, protector, and guide. Toward the end of the 19th century, Pope Leo XIII wrote three prayers to Michael, one long, one medium-sized, and one short. Catholics everywhere took up the short one and recite it still today.

What mysteries is the archangel working out even now in our history, our calendars, and our maps?