St. Joseph is the one person the Church calls “the Worker” — even dedicating a day of the year (May 1) to honor him as such. It’s a strange title — generic, suggestive of an infinity of trades.

And yet it’s unique. St. Joseph is the only one who bears it.

The New Testament tells us, in Greek, that St. Joseph was a “tekton.” And that, too, is a generic word, although somewhat more specific. “Tekton” is Greek for “craftsman” or “artisan.”

So St. Joseph is known for manual labor. His work was not philosophy or theology.

He was a “tekton,” and that meant he was a skilled laborer, obviously known for his work. It’s the name his neighbors remembered him by.

St. Joseph lived in good times for men of his trade. His region was undergoing a building boom. Herod the Great ruled the Holy Land for more than 30 years, and more than any other king in antiquity he was known for his architectural skill.

He commanded the construction of harbors, amphitheaters, marketplaces, racetracks, boulevards, and public baths. Still today, he holds several world records for his building projects.

The whole nation prospered, and the other Judean aristocrats were eager to raise up signs of their prosperity. They wanted mansions and monuments, symbols of their high status and great wealth.

So builders and artisans were in demand, and the future looked endlessly bright. Some of Herod’s projects promised to go on for decades, continuing into the reign of his heirs. From childhood onward, St. Joseph probably worked with crews of men, who commuted together to such worksites.

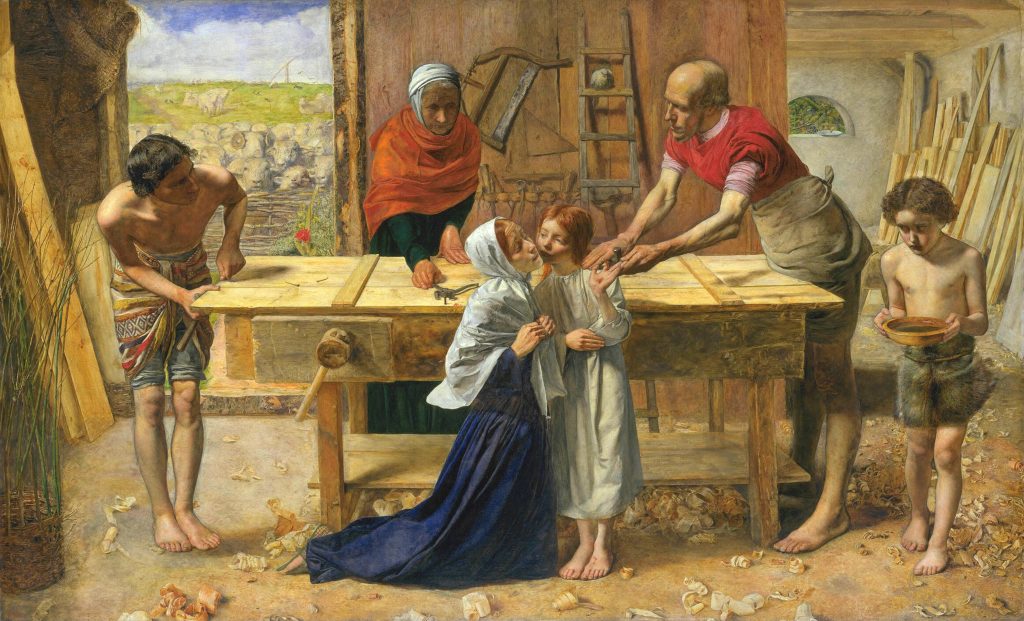

An ancient tradition tells us that St. Joseph’s craft was carpentry, a trade in which he apprenticed his son Jesus. When people were astonished at Jesus’ teaching, they asked, “Isn’t this the carpenter’s son?” (Matthew 13:55).

And all of this is fitting. Spiritual writers since the fourth century have pointed out that Jesus’ earthly father shared two titles with his heavenly Father. Both St. Joseph and God are known as fathers and builders.

As a builder, St. Joseph was godlike. But that divine quality would have been his if he had practiced any other honest trade. Work is part of our basic human vocation and identity; and St. Joseph knew this not because of an angel’s message, but because he knew Scripture.

Some years ago, Pope Francis spoke of the meaning of human labor, and he drew his teaching from the Book of Genesis: “It is clear from the very first pages of the Bible that work is an essential part of human dignity; there we read that ‘the Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it’ (Genesis 2:15). Man is presented as a laborer who works the earth [and] harnesses the forces of nature.”

The Book of Genesis introduces God as a worker (Genesis 2:2) and man, furthermore, as someone made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26). Humanity was made to have dominion over all the creatures of the earth, and sea, and sky. Adam was told to “fill the earth and subdue it” (1:26–28), to “till it and keep it” (2:15). That’s work.

Thus human beings were created with work as a basic part of their nature. All of this happened before the original sin. Work was seen as something good.

In fact, it was holy. We see this in the way the story is told. Adam is commanded to “till” and “keep” the garden. The original Hebrew verbs are “abodah” and “shamar,” which are elsewhere used to describe the work of priests as they tended the sacred rites of the tabernacle.

So, at the moment of his creation, Adam was given a sacred and priestly task. The entirety of the earth was to be his altar and his offering, and his labor was to be his act of sacrifice.

That moment is the true “big bang” in any biblical understanding of work. The event remains like background radiation through the rest of salvation history, informing the way labor and laborers are portrayed in the religion of Israel — and how they’re protected and regulated in Israel’s law.

That doesn’t mean that work is easy. After Adam sinned, God confronted him with the consequences of his actions, and most of them would affect his work: “Cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you” (3:17–18).

Work itself was not a punishment for sin or a consequence of sin. Because of sin, however, work became troublesome and frustrating. Nonetheless, from the beginning, it was holy and good.

And so it was in the life of Jesus, whom St. Paul calls the “New Adam.” In his young life, Jesus reconsecrated labor as he assisted St. Joseph in his workshop.

In time, Jesus took up the work of craftsmen, draftsmen, builders, teachers, and physicians — and he restored it all to its original goodness, lifting it up to his Father in heaven. Later in life, he sailed with fishermen and sanctified their trade. At the wedding feast of Cana he even came to the assistance of bartenders.

In all of the tasks he took up, he established a model for that kind of work. He earned the title that went with his trade. When he was a carpenter, people called him “the carpenter,” as if it was his name. Later on, when he was an itinerant teacher, he was “the teacher,” as if he exemplified the job done at peak performance.

The early Christians delighted when they shared in work that Jesus had done with his hands. So you can see the symbols of all trades inscribed along with the names of Christians throughout the burial chambers in the catacombs.

Jesus learned his approach to work from his father, St. Joseph — who learned it surely from the Book of Genesis. The biblical understanding of labor — as something positive, honorable, and holy — was uniquely Jewish. It did not come naturally to other peoples.

The Greeks, in fact, disdained manual laborers and tried to minimize their participation in democracy. Socrates held that full citizenship should be granted only to the leisured classes — and in fact citizens should be forbidden “to exercise any mechanical craft at all.” Aristotle agreed, adding, “No man can practice virtue who is living the life of a mechanic or laborer.”

The Greek historian Herodotus observed that this attitude toward laborers was universal. “I know that in Thrace and Scythia and Persia and Lydia and nearly all foreign countries, those who learn trades are held in less esteem than the rest of the people, and those who have least to do with artisans’ work … are highly honored.”

Yet the Jews never looked at work that way. We read in the Talmud that “A man has a duty to teach his son a trade. … Anyone who does not teach his son a trade, teaches him to steal.” And elsewhere the rabbis said, “Seven years lasted the famine, but it came not to the craftsman’s door.”

Jews — and later Christians — saw profound dignity in workers and their works. The synagogues and churches in antiquity were filled with laborers, who worshiped a Laborer and whose Scriptures preserved not the arguments of philosophers, but the stories of people who got work done. Abel was a herdsman. Noah was a sailor. Jacob leaned into a plow. Peter and John were fishermen. Paul made tents and canopies.

These men got dirty and sweaty every day. And so the tradition-minded Greeks and Romans could dismiss them as ignoble.

The idea that ordinary labor had dignity — the idea that ordinary work could be something divine — this was one of those crazy Christian ideas that scandalized the pagan world. It was like the idea of a crucified God, or of ordinary people eating God at Mass.

Pagans mocked them. But Christians seemed to revel in every insult. The Church Fathers didn’t hesitate to portray Jesus working at various trades. And everyone recognized this as a radical idea.

The pagan gods were projections of the upper classes, and the Greek and Roman myths were narratives of the horrible mischief of a leisurely life.

But the God of the New Testament was a carpenter, whose earthly father was a carpenter, and whose Father in heaven was not drinking and womanizing, but always toiling. Jesus told his opponents, “My Father is working still, and I am working” (John 5:17).

The lesson was not lost on the early Christians. St. Clement of Alexandria, writing around A.D. 190, reminded new converts that there was no need for them to quit their jobs: “Tend to your farming if you’re a farmer; but know God while you labor in the fields. Sail if navigation is your profession, but invoke always the celestial pilot.”

And such preaching was effective. It converted people in every walk of life. St. Clement’s contemporary, Tertullian of Carthage, boasted of the Church’s explosive growth. “We emerged only yesterday, and we have filled every place among you — cities, islands, fortresses, towns, marketplaces, military camps, tribes, companies, palace, senate, forum. We have left nothing to you but the temples of your gods.”

In the world, Christians were as omnipresent as God; and, like their God, they were working still. The new Christian faith led them not to abandon their duties, but to excel in them. And this distinguished Christianity from other world religions.

Their work was holy. They learned this from Jesus, who had learned it from his father — St. Joseph the Worker.