Research suggests that the childhood memories which stick with us the most are the ones attached to strong emotional responses, events that embody the nature of our childhood, or what matters most to us as adults.

One of my earliest memories is from Sunday Mass when I was about 4 years old. Our family was sitting in the first pew, close enough to see every movement and hear every prayer made by the priest. As I rubbed my knees across the cracked leather kneeler, I scooted close to my mother to ask her a question about something inconsequential. She leaned down and with the most serious tone I’d ever heard her use said, “We never talk during the consecration,” and turned her head back to the altar with laser focus.

I think about this experience regularly at Mass, moreso now that I have young children squirming next to me in the pew. On the way home, my mother didn’t offer to explain the liturgy or what the Eucharist was. In fact, we didn’t really talk about Communion again until I was preparing to receive it for the first time.

But her tone and focus led me to conclude that something serious was happening on the altar. I didn’t experience her admonition as punitive; it was my earliest introduction to reverence, of reserving time and attention for things that are sacred.

This was the first of three lessons my mother gave me on the Eucharist.

The second came nearly three decades later. Six months before the world went into lockdown, my mother was rendered homebound. Two years into a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), she could not physically get out the door for Mass. Her muscles were atrophying, her breathing compromised, and the routine of getting dressed and “ready” was too laborious for her and my father, her caregiver.

My parents, once extraordinary ministers of the Eucharist, were soon at the mercy of others to bring them Communion. A neighbor eventually began to bring them two hosts on Tuesday mornings, and when I would visit them, I would take my mother’s pix to and from Sunday Mass. Eventually I would only bring back one host for the two of them, as she could only consume a tiny morsel lest she choke.

During those privileged moments of giving my weary parents Communion, I thought of Pope Francis’ description of the Eucharist as “medicine for the sick.” To date, there is no cure for ALS. The only medication on the market promises to extend patients’ lives for several weeks or months.

Despite a hope for a miracle, we all knew that my mom’s saving medicine would be the Eucharist. “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life,” the Lord said (John 6:54). As her earthly life was nearing its completion and as her quality of life diminished, my mom held on to that promise. In fact, she whispered to me one evening, “People with death sentences — either in prison or with a terminal illness — think about their last meal. I hope mine is the Eucharist.”

My mother was teaching me in those moments of weakness — when stretching out her tongue to receive the host took extraordinary effort — to think about the things that will not pass away. She was also showing me that it was the medicine I needed to fortify myself for the inevitable.

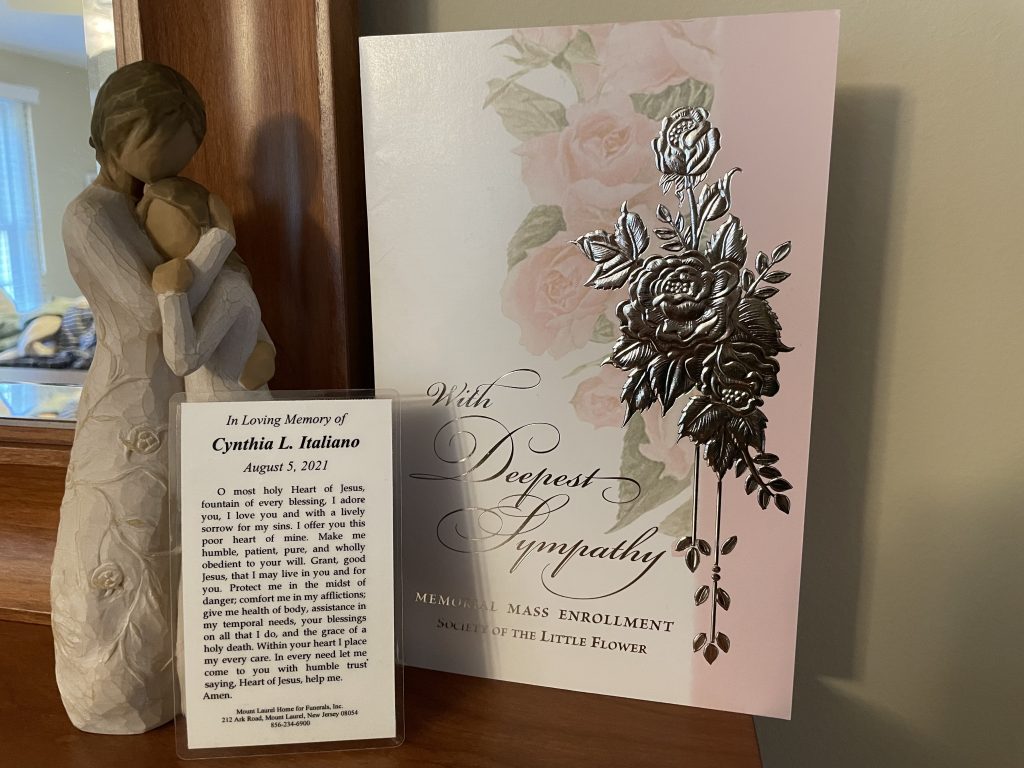

On Aug. 10 of this year, I stood next to my mother’s casket, greeting nearly 300 people who came to pay their respects at her wake. Among those in line were members of our hometown parish, where my mother had worked in the rectory. More than one parishioner shared with me that my mom was known for spending an inordinate amount of time with the bereaved who came to the office seeking Mass cards.

I learned that my mom often asked them to share about the person who had died, and how she could pray for those who were left behind. This small act of engaging people in conversation with sincere curiosity turned out to be a bigger consolation to parishioners than we realized.

I was touched but not surprised to learn this about her, because the third lesson my mother delivered on the Eucharist was an explicit one: She taught my brother and me about the importance of having the sacrifice of the Mass offered for the dead.

Throughout my childhood I remember regularly stopping by the parish to pick up Mass cards for friends, relatives, and neighbors. My mom was the one who made sure that our extended family gathered together at Mass to pray for our deceased loved ones on their birthdays or the anniversary of their deaths.

In doing this, my mom made sure that it was the Eucharist that brought us together to mark moments of mourning and remembrance. But it was also the Eucharist that joined us with our deceased loved ones. She taught us that the dead are gathered around the altar with us at every Mass, albeit in an invisible way, since it’s where heaven meets earth.

In the weeks and months since her funeral, my father, brother, and I have opened several hundred sympathy cards. Included in that count were nearly 150 Mass cards. It has been an enormous consolation that my mom is reaping what she sowed.

Since I first read them, I have often recounted the words of Pope Francis to young people, delivered on his 2019 trip to Romania:

“As you continue to grow in every way — stronger, older, and even in importance — do not forget the most beautiful and worthwhile lesson you learned at home. It is the wisdom that comes from age. When you grow up, do not forget your mother and your grandmother, and the simple but robust faith that gave them the strength and tenacity to keep going and not to give up. It is a reason for you to give thanks and to ask for the generosity, courage, and selflessness of a “home-grown” faith that is unobtrusive, yet slowly but surely builds up the kingdom of God.”

I grieve that my children will not remember their grandmother. But I am consoled by the Holy Father’s words, because I will pass down my mother’s lessons on the Eucharist to them. And at the altar they will share that meal with their grandmother as often as they frequent it, the saving medicine for us all.