On a recent early Saturday morning, I wrote a letter of condolence, arranged a doctor’s appointment, bought a book, scrolled through social media and searched for cheap flights to Chicago.

All using an iPad while I was still in bed.

Rapid communications technology has shrunk our world and sped up time. It affects who we are in contact with and what we are aware of, and how we think and behave in nearly all aspects of our lives.

Our faith is not immune to these effects.

Faith and evangelization

Christianity has historically been an “early adopter” of technological change, even leading it. Early Christian missionaries carried the Scriptures in the innovative form of bound manuscripts (rather than using the Jewish long scrolls, which were more expensive to make and less portable). Monks created lettering that was clear to read and easy to copy. Several centuries later, Father Patrick Peyton and Ven. Fulton Sheen pioneered Catholic broadcasting.

Today’s internet appears to be tailor-made for evangelization. Some sectors of Christianity, e.g., Protestant megachurches, enthusiastically and effectively incorporate music and video to spread their message. In the Catholic world, Word on Fire shares the gospel through videos and podcasts, and EWTN has a global reach, beaming its programming into television screens in 140 countries, 24-hours a day. Research shows that people who do not normally go to a physical church to worship are more likely to access the church’s website, particularly if it is easy to use, visually appealing and entertaining. Popular prayer apps such as Hallow target young people.

But ready access, ease of control, speed, and convenience are not necessarily Catholic values. What is attractive is not necessarily good. And what is good is not always good in unlimited quantities.

The digital divide

Some of the long-term effects of technological shifts are truly disconcerting. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed huge global inequalities between the digital haves and have-nots. Inner-city schools have taken the worst of the brunt of damage to children’s educational attainment, according to a recent study by the Pew Research Center. And the older generation can struggle with such things as using touch screens, filling out online forms, and keeping in touch with family.

The dark realities tend to pile up.

Any priest who hears confessions will tell you that pornography addiction is widespread.

Our personal information, including the details of our browsing history and, alarmingly, the contents of our private messages, are financially valuable, routinely sold to advertisers, and used to manipulate the content we see on our social media feeds. Young people — teenage girls and young women especially — are under daily pressure to conform to impossibly glossy ideals in all aspects of their life. Research shows that we are losing our ability to concentrate and retain the information we consume.

Given that we cannot simply unplug forever, how should Catholics use communications technology in all its forms?

Ways forward

The question is big and complex and requires both prayer and serious study. To date, neither the Church nor Catholic universities have responded in sufficient depth to the growth of technology’s influence and vast reach. I am hoping that the Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies at USC, which I lead, can be a center for such a conversation. And in the meantime, I offer one principle and one value as my modest contribution to that important question.

The Principle and Foundation of St. Ignatius of Loyola is that we should make use of things to the extent that they help toward what we are created for — which is loving and serving God. If they don’t help, then don’t use them.

That means reflecting on how much we use technology and how much we end up being used by it. No easy task when new software springs up overnight and we are so easily distracted.

The value is the spiritual need for real community. Active belonging to a religious community is declining and religiously unaffiliated people (the “nones”), are mostly young adults and make up about a quarter of the American population. Yet many young people yearn for a sense of belonging.

The community that technology creates by algorithms drives us toward people who agree with us and away from those who don’t. And screen time is fundamentally time spent alone.

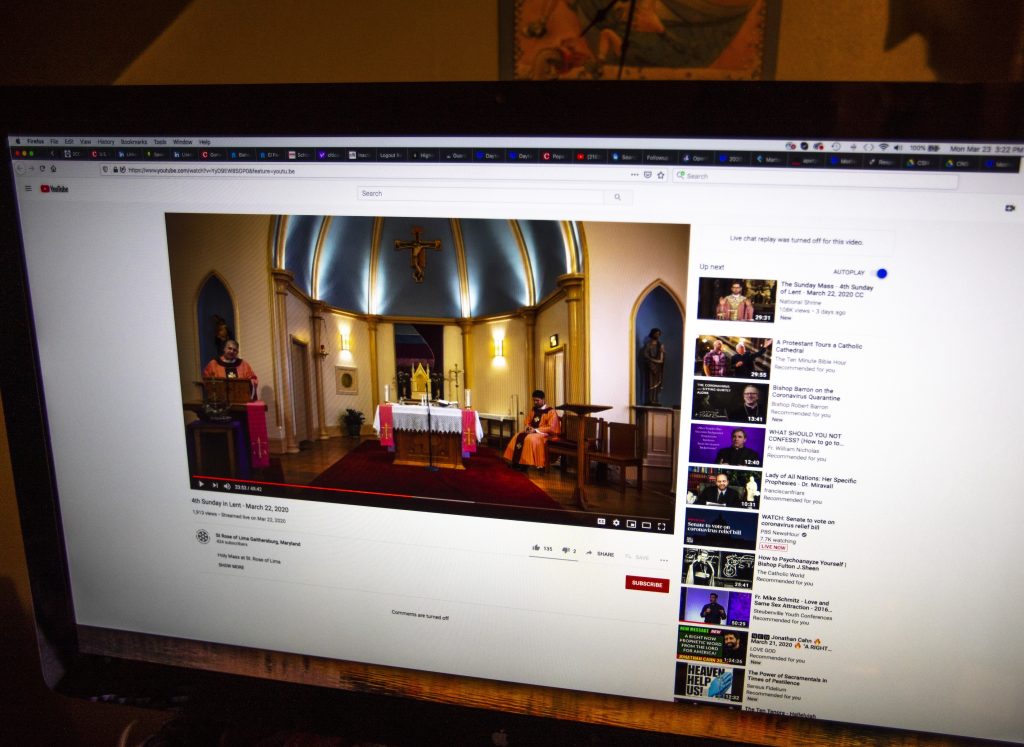

During the pandemic, many parishes livestreamed Masses and prayer vigils, bringing comfort and a sense of continuity during widespread uncertainty and disruption.

But am I the only person who has watched online events where I have simultaneously done other things, like scrolling through social media, or fast-forwarded when I got bored? Physically attending Mass needs a different level of commitment. Showing up, gathering with people we may not know or feeling we have a lot in common with can be time-consuming and inconvenient.

And that’s where the blessing lies — because our faith is about what we contribute, not only about what we get.