And — just like that — millions of parents found themselves educating their children at home.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has forced U.S. school districts to impose full or partial closure of their buildings. Some districts were hit by COVID-19 outbreaks just days after opening for the academic year, so the kids went right back home.

Parents and children are now, without any warning or preparation, in an unfamiliar and very challenging teacher-student relationship. Memes on social media make much of the difficulties. In a tweet that went viral, TV producer Shonda Rhimes declared, “Been homeschooling a 6-year old and 8-year old for one hour and 11 minutes. Teachers deserve to make a billion dollars a year. Or a week.”

It’s not easy.

But parents should know that they’re equipped for this, by nature and by the grace of vocation. That’s the official teaching of the Catholic Church. In 1965 the Second Vatican Council declared: “Since parents have given children their life, they are bound by the most serious obligation to educate their offspring and therefore must be recognized as the primary and principal educators” (“Gravissimum Educationis,” 3).

The Good Book says that there is nothing new under the sun (Ecclesiastes 1:9), and Catholic history unfailingly bears this out. That’s a good thing, because it means we can find models for just about any task in the lives of the saints, and we can also find intercessors to come to our aid as we pray for sanity, endurance, and maybe a smidgen of wisdom.

So, yes, our families are not the first to find itself suddenly homeschooling. We can look to our spiritual ancestors for good precedents and remarkable prayer support.

School of saints

Basil and Emmelia were fairly well off, but they never had it easy. They were born in Cappadocia in the early years of the fourth century, when the practice of Christianity was still a capital crime in the Roman Empire. Basil’s family had to uproot itself and flee persecution. Together, the couple had 10 children, nine of whom lived to adulthood and five of whom would eventually be canonized as saints.

Basil was a lawyer and renowned teacher of rhetoric — a very busy man. But he made the decision to educate his children himself. He may have been put off by the standard school curriculum of his time, which was still deeply pagan; or he may just have thought he could do the job better than the local teachers ever could.

Whatever the case, his decision was vindicated in the careers of his older children. His son Basil Jr. was, according to one biographer, always following his dad around. “As we see foals and calves skipping beside their mothers from their birth,” so little Basil was always “running close beside” big Basil.

Basil Jr. went on to study in some of the best schools on earth: in Athens and in the imperial capital, Constantinople. Still following after his father, the young man excelled in rhetoric and studied under the greatest rhetorician of his time, Libanius, the tutor of emperors.

“This is what befell [young Basil],” said St. Gregory of Nazianzus, who knew him. “He had at home a model of virtue in well-doing, the very sight of which made him excellent from the first.”

The elder Basil was obviously winning at the game of home education. But he died before he could follow through with children who were later in the birth order.

His firstborn daughter, Macrina, stepped up and volunteered to continue her father’s work of teaching the family. And with no training other than paternal example, she excelled. Among Macrina’s students was her little brother Gregory — known to history as St. Gregory of Nyssa — who wrote her biography.

She “became all things” to her younger siblings, he wrote. She was “father, teacher, tutor, mother, giver of all good advice.” She was a learner herself, who pursued the studies that fascinated her — committing the entire Psalter to memory.

Her brothers were inspired to follow her example and instruction. Peter (now known as St. Peter of Sebaste) became a philosopher and then a bishop, but he also was “clever in every art that involves hand-work.” Thus, it seems that Macrina taught shop class and home economics, as well as the usual run of academic courses. Peter was “always looking to his sister as the model of all good,” Gregory tells us, and “he advanced to … a height of virtue.”

The family of Basil and Emmelia faced extraordinary challenges. But they made education a priority, and they achieved success by any worldly measure, and singular success when measured by the rule of faith.

Basil Jr. is venerated today as St. Basil the Great, a Doctor of the Church, monastic founder and bishop. Peter and Gregory were also bishops now revered as saints. Their brother Naucratius excelled as a jurist and scholar before becoming a hermit, and he, too, has been canonized.

But probably none is so beloved among the people of the Eastern Churches as St. Macrina, who was their teacher.

More to the story

Sir Thomas More was a lawyer of the 16th century whose career went from glory to glory. He was, in orderly succession, speaker of the House of Commons in Parliament; chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster; and finally lord chancellor of all England, serving at the court of King Henry VIII.

Yet he considered his most important job to be father and teacher to his five children. He wrote to his oldest daughter that he would gladly change the course of his professional life if he thought it might benefit his children.

“I assure you that, rather than allow my children to be idle and slothful, I would make a sacrifice of wealth, and bid adieu to other cares and business, to attend my children and my family.”

He said his domestic duties “count as business,” and he gave himself to them wholeheartedly. Up until the moment he entered royal service, he was his children’s primary instructor in every subject. When his last job prevented him from doing this personally, he personally chose their tutor and supervised the man’s work.

Unusual for his time, More believed that his daughters should receive the same educational opportunities as his sons. His daughter Meg was his star pupil, and he imposed daunting assignments for her.

He was a strong believer in translation as the best way to learn a language or understand a work of literature. So Margaret, from an early age, rendered books from Greek and Latin into her native English. But she also came to compose both prose and poetry in the classical languages.

Judging by Meg’s achievements, one might imagine More to be a harsh taskmaster. But his daughter recalled that his lessons were filled with laughter. And he made even the reading of tragedy memorable by his ironic humor and taste for the absurd.

Meg would herself become an accomplished scholar and writer. She translated works by her great contemporary Erasmus from Latin into English. But she is best known as the custodian of her father’s memory.

When he died as a martyr — beheaded at the order of King Henry — it was Meg who retrieved his head from its display on London Bridge. Meg’s husband, William, wrote the biography of More that launched his cause for canonization, which was realized in 1935.

A Blaise of glory

He is one of the greatest prose stylists ever to write in French. And he also ranks among the greatest scientists in history. His name itself is proverbial, attached to the “wager” he made about God’s existence.

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) stands at the pinnacle of achievement in diverse fields. Yet he died before his fortieth birthday.

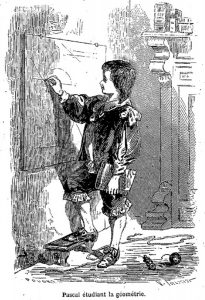

His achievements all began with lessons at home.

Blaise’s father, Étienne, was a tax collector by profession, but he was also a brilliant humanist and mathematician. Contrarian by nature, he took a dim view of the schools in France. He had his own ideas about education. Left a widower when his children were very young, he decided to devote his nonworking moments to their instruction.

Étienne was a strong believer in child-led education, and he tried to instill a sense of confidence in his children. The historian Marvin O’Connell explained: “Étienne concentrated his instruction on attracting a childish imagination or on answering a young boy’s questions. How does gunpowder work? Why does a knife striking a porcelain plate make a certain sound that stops when one puts one’s hand on the plate?”

Étienne believed that math was entirely too much fun and, if taught, could only distract a student from other pursuits. So he hid away all the math books, actually placing them under lock and key.

Somehow, though, young Blaise began to think in mathematical terms. At 9 years old, he invented his own terminology to describe the phenomena he observed in numbers and geometry. By the time his father discovered these secret studies, the little boy had replicated one of Euclid’s propositions on his own.

Better with Betty

Betty and William Seton raised 11 children, five of their own and six of William’s siblings who were still young when his parents died. Theirs was a moneyed family in Manhattan at the end of the 1700s. But the fortunes of the family business rose and fell.

Like other New York aristocrats, they sent their older children away to boarding schools in New Jersey. The younger children went to local schools.

At a certain point, however, Betty realized that it was more than a full-time job just to get all those children dressed and ready. Sending them out, she said, “through snow and wet will give me more trouble than keeping them at home.”

So, for the sake of her own sanity, she decided to become the teacher for her younger children and give the lessons at home. Betty Seton’s biographer, Joseph Irvin, noted that the “little school could hardly have been conducted on rigid lines,” since Betty had to deal constantly with the “needs and distractions” of toddlers and a baby.

Nevertheless, that “homely little classroom” had “great significance, for it was … the forerunner of every Catholic classroom in the United States.”

After her husband’s death, Betty converted to Catholicism. She would go on to found a religious order, the Sisters of Charity, with whom she laid the foundation for the vast Catholic school system that developed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

We venerate her today as St. Elizabeth Ann Seton.

Lessons learned

Catholic parents can surely deal with whatever 2020 might send their way. They have the example of the saints to follow. They have the prayer of the saints to invoke for help.

From the saints they can learn to relax and laugh with their kids, to keep focused on the goal, to let go of lesser things, and to expect the kind of surprises that are God’s hallmark.

Education is a task that parents were created for — and called for.

You got this.