Jesus is just what the doctor ordered — every doctor, in fact, when the doctors in question are the Doctors of the Church.

And the most recently named of those — though the earliest in history — is St. Irenaeus of Lyon.

St. Irenaeus was born in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) around the year 130, and as a youth converted to Christianity under the guidance of Bishop Polycarp. St. Bishop Polycarp in turn had been a disciple of the apostle St. John.

On Jan. 21 of this year, Pope Francis named St. Irenaeus as the 37th Doctor of the Church, giving him the title “Doctor of Unity.” The classical sense of the word “doctor” is “teacher,” and the saints who bear that title are considered history’s great masters of Christian doctrine.

This Lent, as we draw closer to Jesus Christ, it will be good to consult this teacher, the better to see the Lord as he was.

His pedigree was remarkable. His tutor, St. Polycarp, had learned about Jesus from the closest of eyewitnesses. St. John was the “disciple whom Jesus loved” (John 13:23, 20:2, 21:7, 20), who had laid his head on Jesus’ breast (John 13:23, 25, 21:20). St. Polycarp, though very old when St. Irenaeus knew him, remembered St. John’s memories vividly, as if they were his own.

He also took up St. John’s causes. St. John was the apostle much concerned about heresy and heretics — those who taught false doctrine about Jesus Christ (2 John 1:7, 9–10, Revelation 3:15). St. Polycarp shared this passion and, in his Letter to the Philippians, railed against “false brethren” who “draw away vain men into error.”

Those particular heretics, called Docetists, believed that Jesus was not truly human, but rather only seemed to be human. He was simply God, they taught, and his human appearance was a cleverly wrought illusion. When St. Polycarp met Marcion, a famous teacher of heresy, Marcion said to him, “Don’t you know who I am?” And St. Polycarp replied, “I do know you. You’re the firstborn of Satan.”

St. Irenaeus, however, took the condemnation of heresy to the next level. By the middle of the second century, Christianity was still fairly new on the world scene, but already there was great confusion about Jesus — who and what he was, what he did and what he taught.

The confusion spilled from a new category of heresy: Gnosticism. At the heart of Gnosticism was the belief that people are saved not by faith, but by knowledge (“gnosis,” in Greek). Jesus, the Gnostics believed, had come into the world to reveal secret mysteries to an elite class of spiritual people. He was their savior exclusively, and he was uninterested in the common rabble, who could not possibly understand or accept his message.

The Gnostic gospel was revealed privately, secretly, and was quite different from the gospel preached by the mainstream Church. But it differed in different ways, depending on the Gnostic teacher. Since it was all a secret, passed down in a whisper, only the teachers could explain it, and the Gnostic teachers disagreed as fundamentally with one another as they did with the Catholic Church.

Yet they succeeded to a remarkable degree by appealing to the pride of individual Christians — telling them they were superior to ordinary folks in their congregation and ready to receive special messages from Jesus. Gnosticism was like a religious country club.

The heresy was especially dangerous because it hawked its false Jesus not to pagans, but to Christians. It was a parasite on the Church, diverting and perverting the faith of those who had accepted Jesus, but were nonetheless gullible and vain.

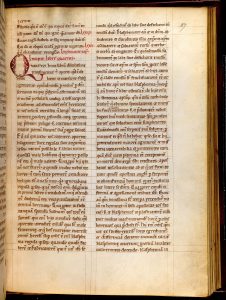

This alarmed St. Irenaeus, and he resolved to do something about it — something very big. In response to the proliferation of Gnostic teachers, he wrote a sprawling, multivolume work titled “Against Heresies.” In five books he examined the doctrine of every false teacher whose works he could acquire. He quoted extensively from their writings, and he refuted them decisively, showing that their tenets could not be reconciled with the Church’s authoritative Scriptures — or with the beliefs that Christians had held dear through the 150 years since Jesus’ ascension to heaven.

St. Irenaeus urged his readers not to pay any mind to “secret” doctrine reserved only for the elite. He directed their attention instead to Christian doctrine that was public and objectively verifiable: namely, Scripture, Tradition, and Magisterium (the teaching of the bishops and especially the pope).

The true doctrine of Jesus was not something concealed. It was proclaimed in the assembly. It was interpreted soundly in preaching. It was applied in the decisions of the clergy. It was embedded in the sacraments and prayers of the liturgy. St. Irenaeus himself could confirm that these sources had been reliable from the time of the apostle John and through the long life of St. Polycarp. The particular claims of the Gnostic teachers, however, had been consistently and authoritatively rejected.

The great historian Johannes Quasten called St. Irenaeus “the founder of Christian theology.” In our own time, the historian James Papandrea has called him “the first theologian.” Appearing early in Christian history, he provided the first extensive, reasoned reflection on the data of divine revelation — what God had revealed by taking flesh in Jesus Christ.

“Against Heresies” is a rambling work and sometimes repetitive. St. Irenaeus took on a variety of wayward teachers and sects and addressed them one by one. So there was much overlap, many errors held in common, but also significant differences. The Ebionites denied the divinity and pre-existence of Jesus. The Docetists denied his humanity and his ability to suffer. The Marcionites held that the Old Testament preached a different God than the New, and that Jesus opposed the Old Testament God. And there were many others, in many other shades of falsity.

St. Irenaeus didn’t simply condemn the teachers and reject their doctrine. He consistently articulated the positive truth drawn from Christianity’s commonly accepted sources. He did what theologians ever afterward have imitated.

His teaching about Jesus was detailed, clear, scriptural, and inspiring.

He taught that Jesus Christ is truly God — and uniquely so. “Jesus Christ [is] our Lord and God and Savior and King.” What can be said of Jesus “cannot be said of anyone else who ever lived, that he is himself in his own right God and Lord.” Moreover, “those who assert that he was simply a mere man, begotten by Joseph, remain in the slavery of the old disobedience, and are in a state of death since they have not yet been joined to the Word of God the Father.”

He taught that Jesus Christ is truly human. St. Irenaeus insisted that “the divine Scriptures do testify both these things of [Jesus]: that he had in himself that pre-eminent birth that is from the Most High Father; and also that he experienced that pre-eminent generation which is from the Virgin. Also, that he was a man without comeliness, and liable to suffering; that he sat upon the foal of a donkey; that he was given vinegar and gall to drink; that he was despised among the people, and humbled himself even to death.”

He taught that Christ pre-existed the Incarnation. “It has been clearly demonstrated that the Word, who existed in the beginning with God, by whom all things were made … became a man liable to suffering. … The Son of God did not then begin to exist. He was with the Father from the beginning. But, when he became incarnate and was made man, he commenced afresh the long line of human beings, and furnished us, in a brief, comprehensive manner, with salvation; so that what we had lost in Adam — namely, to be according to the image and likeness of God — that we might recover in Christ Jesus.”

He taught that Jesus is truly present today in the Eucharist. Jesus “has declared the cup, a part of creation, to be his own Blood, from which he causes our blood to flow; and the bread, a part of creation, he has established as his own Body, from which he gives increase to our bodies.” This sacrament, according to St. Irenaeus, contains the Lord’s body, blood, and divinity: “The Word of God becomes the Eucharist, which is the body and blood of Christ.”

In one breathtaking passage in Book 3 of “Against Heresies,” St. Irenaeus summarizes the entire history of salvation, beginning with the word’s pre-existence and culminating in the gift of the Mass.

For such reflections, the “first theologian” has become the 37th Doctor. He does not always speak with the precision that would be required in later centuries. He was responding to the heresies of his day; but heresy is like a virus, always producing new variants that resist earlier remedies. St. Irenaeus could not have anticipated the strange heresies of the fourth century or the 21st.

What he did, however, was provide believers with a test for the virus. He gave us a way to tell the real Jesus from the false that were on offer from heretics. He knew that we could not truly love a Lord we did not truly know.