One thing I hope to ask Jesus face-to-face one day is why the greatest writers of history in the English language were all fiercely against the Church.

Edward Gibbon, who flirted with Catholicism as a young man, was disinherited by his father for the same and then abjured the faith, as all who have read his monumental work “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” know.

Thomas Macaulay, a poet and parliamentarian of great eloquence, was the author of a well-known “History of England.” The book is another masterpiece of prose. However, as a Whig historian, Macaulay is consistently and infuriatingly anti-Catholic.

The third writer I’d rank among the greats is the American historian Francis Parkman, whose writing reveals the ambivalence of a brilliant man who admired some aspects of the Faith and those who profess it, but who also harbored some fanatical prejudice against religion.

For example, Parkman wrote a great line about the founder of the Society of Jesus: “It was an evil day for new-born Protestantism, when a French artilleryman fired a shot that struck down Ignatius Loyola in the breach of Pamplona.”

Of the early Jesuits, he wrote that “their marvelous training roused into action a mighty power and made it as subservient as those great material forces which modern science has learned to awaken and govern.” A few pages later, he calls the formation given by the order, “this horrible violence to the noblest qualities of manhood, joined to that equivocal system of morality. …”

Perhaps Parkman is best known for his books about the French colonies in North America, including “The Jesuits in North America in the Seventeenth Century,” which profiles the North American Martyrs, eight Jesuits whose feast day the Church celebrates Oct. 19.

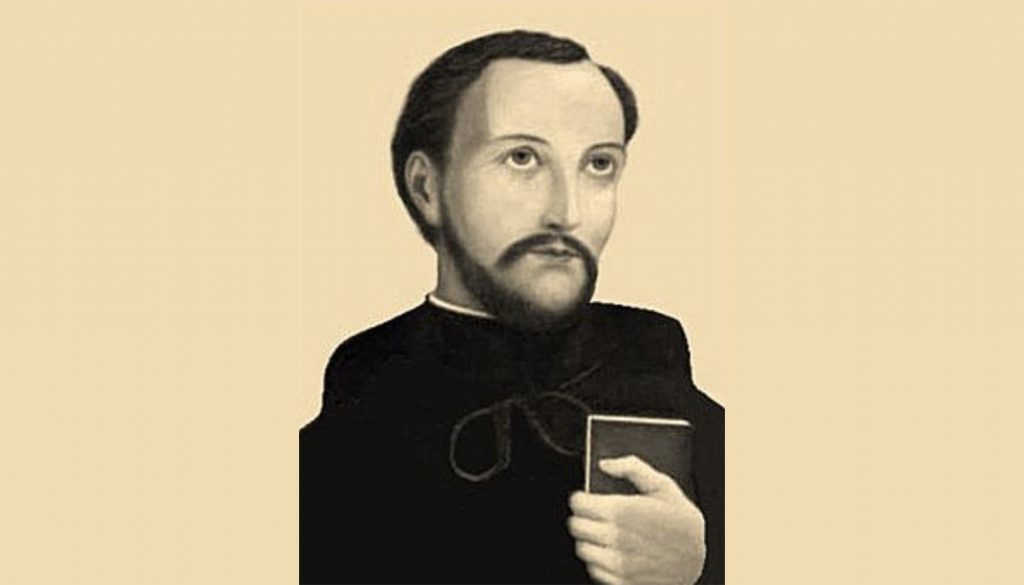

I picked up “The Jesuits in North America” to learn more about St. Noel Chabanel, for whom a parish in my diocese is named. I remember our bishop once said that he admired St. Noel’s “holy frustration,” and that he was a study in “holy failure.” As a young priest, I was not as appreciative of that kind of sanctity as I now am.

Parkman wrote about the tremendous disappointment Father Chabanel experienced when he came to the missions: “He detested the Indian life — the smoke, the vermin, the filthy food, the impossibility of privacy. He could not study by the smoky lodge-fire, among the noisy crowd of men and squaws, with their dogs and their restless, screeching children. He had a natural inaptitude to learning the language, and labored at it for five years with scarcely a sign of progress.”

Father Rageneau, his superior, wrote after his death that “even after three, four, five years of study of the Indian language, he made such little progress that he could hardly be understood even in the most ordinary conversation.” Father Chabanel had been a teacher of rhetoric in France, a man with a classical education, but he could not speak the language of the people he hoped to convert and serve. Father Rageneau said this was “particularly painful.”

The rationalist historian noted the priest’s frustration: “The Devil whispered into his ear: ‘Let him procure his release from these barren and revolting toils, and return to France.’ ” Father Chabanel’s response to the temptation to leave the mission was to vow in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament to remain in Canada until his death.

At this time, the Iroquois nation warred against the Hurons whom the missionaries were converting in large numbers. Several of Father Chabanel’s companions were killed before he was. He knew that he lived in danger, but he was obedient, accepting wherever he was sent and committed to giving his life for the faith.

Parkman includes part of a letter he wrote to his brother in a footnote. “I am very apprehensive by nature,” the saint wrote, “But now that I am in the greatest danger, and it seems that death cannot be far away, I am not afraid anymore. That presence of mind does not come from my own powers.”

On Dec. 5, 1649, Father Chabanel received an order to go to the mission on what was called Christian Island. On the way, he and his Huron guides were attacked at night by Iroquois warriors. His companions fled but Father Chabanel could not keep up. When dawn came, he began to walk toward his destination. He was killed by a Huron apostate who was disgusted by the disasters the faith of the missionaries had caused his people.

St. Chabanel’s story is less known than that of St. John de Brebeuf and St. Isaac Jogues, whose tremendous bravery and talent for evangelization made them giants. I think St. Chabanel might have inspired Brian Moore’s insightful novel, “Black Robe,” with its priest-hero Father Laforgue, who also suffers the conflicts that come from an encounter between two cultures.

The poet John Milton, when he became blind, wrote that, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” St. Chabanel stood and waited in what an author once called a “unique martyrdom.”

Peter Ambrose wrote of him, “Like the life of the suffering Christ he served so faithfully, Noel’s life seemed one of apparent failure. Noel Chabanel is the silent hero of the hard trail, a patron of misfits, patron of the lonely, disappointed and abandoned, the patron of square pegs in round holes.”

What can be said after that but, “St. Noel, pray for us”?