In broadcast media and shopping centers, Christmas carols appear early, but vanish before the last of your leftover Christmas cookies.

In the Church, however, there is one song that continues its run through much of the year.

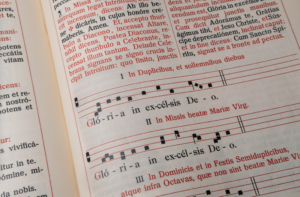

“Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to people of good will.” The Church calls it the “Gloria,” and it is a fixture of the Mass on Sundays and feast days.

In many ways it was the first Christmas carol. St. Luke presents its debut in his account of Jesus’ birth. “An angel” speaks the words, backed up by “a multitude of the heavenly host” (Luke 2:13–14). And the original audience was not shoppers, but “shepherds in that region living in the fields and keeping the night watch over their flock” (2:8).

The Gospel doesn’t say the angels sang the words, but Christians have always interpreted the passage that way. We still sing: “Angels we have heard on high / sweetly singing o’er the plain.”

In the earliest days of the Church, some unknown poet took the angels’ lines and used them as the opening of an exuberant song — resulting in the prayer we still sing at a typical Sunday Mass.

In ancient times, for music in worship, the Church usually favored lyrics from the Bible, either the Psalms of King David or canticles such as Mary’s Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55) or the songs of Simeon (Luke 2:29–32) and Zechariah (Luke 1:68–79).

But Christians sometimes produced new songs, composed in the style of the biblical psalms. They were called “personal psalms” or “private psalms” (in Latin, “psalmi idiotici”). They were very common, but only three have survived from antiquity, and only one of them was made a permanent part of the Mass. Catholics in the west know it today as the “Gloria.”

It begins with the words of the Gospel, but goes on to praise the Lord in what seems to be a mashup of outbursts:

We praise you,

we bless you,

we adore you,

we glorify you,

we give you thanks for your great glory.

The personal psalms were often improvised on the spot, and the “Gloria” captures the qualities of spontaneous praise and love for God.

Mention of it first appears in the records of the ancient Roman Church, which were preserved in “The Book of the Popes.” There we find that the song was introduced into the Mass by Pope Telesphorus, who reigned from A.D. 128 to 139. But he didn’t write the “Gloria.” It was a Greek text already in use in the Eastern churches. Greek was for the first three centuries the language of the Roman liturgy, too, so it was a perfect fit.

In the eastern lands, the “Gloria” had been (and remained) a daily devotion. It was offered at dawn as the first prayer of the day. As the Christmas song first announced the Savior’s birth, so morning prayer — with the “Gloria” — served as a kind of “Christmas” for each day.

But the Roman Church, at least in the beginning, employed the “Gloria” only once a year. It was a Christmas song, and so it belonged in the midnight Mass for Christmas Eve — thus replicating for the congregation the experience of Bethlehem’s shepherds, who watched their flocks by night.

Such was the case for centuries. By the end of the fourth century, the Romans had abandoned liturgical Greek and were celebrating Mass in the Latin vernacular. Around the year A.D. 360, St. Hilary of Poitiers (who had spent a busy exile in the East) produced a Latin translation of the “Gloria.”

Even then, however, the “Gloria” was still the exclusive property of the bishops, and they could use it only at Christmas.

It would be another 100 years and more before Pope Symmachus I (A.D. 498-514) relaxed the restrictions on the “Gloria.” He extended its use to Sundays and feast days. He even allowed simple priests to intone the “Gloria” — but only at Easter.

It was not till the second millennium that the “Gloria” invaded and pervaded the liturgical year of the Western Church. It became a distinguishing mark of Sundays and feast days. It was, and is still, suppressed during the seasons of Advent and Lent. In Advent, it would be inappropriate because the Church is awaiting Christmas, and the “Gloria” is a song proper to Christmas. And in the solemn season of Lent its exuberance would seem out of place.

The “Gloria” is a “doxology,” which literally means a word of praise. In the Church it is known as “The Great Doxology,” because of its length, its status, and its antiquity. It has been the subject of profound commentaries down the ages.

Dynamic, ecstatic, the “Gloria” serves as an outpost of Christmas even in times most distant — even in the heat of the summer.

The 20th-century liturgical theologian Maurice Zundel waxed poetic when he spoke of the “Gloria”: “What a conquest it would be, what a dream, or rather what an inexpressible reality, what an advance in depth, and what a peaceful victory, if you would but genuinely believe the words you utter, and would but put your entire soul into the praise to which the Church invites you, in her Gloria, that it may be Christmas in the world, through your heart, today.”