During this year’s liturgical season of Lent, Angelus is featuring a four-part series of interviews with Catholic scholars on the “Four Last Things” in Christian eschatology: death, judgment, heaven, and hell.

David Mills is editor of the Memento Mori Initiative and its website, HourOfOurDeath.org. The Initiative’s goal is “to renew and develop Catholic religious and cultural practices in care for the dying and the dead.” He spoke with Angelus about the first of the four Last Things.

What do Americans make of death?

Something you don’t think about until you have to. It’s not even the old ideal of “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” The modern American ideal seems to be “eat, drink, and be merry, because it’s fun.” We have so much money, and medicine protects us from sickness and puts death so far away, it’s easier than ever to put dying out of our minds.

At the same time, people don’t seem to hate death the way they used to. They may hate particular deaths, but they don’t hate death itself. They don’t see it as an evil that should not be. Maybe it’s another effect of our wealth and comfort. We accept that all good things must come to an end.

That’s more reasonable than it may seem. I suspect a lot of people feel the way I do, at least people over 55. I don’t fear death, except for the effect it will have on those I love. As long as my wife is alive, I want to live. I can understand why some people don’t feel the need for an afterlife, that they’d had a good run and that’s that.

Otherwise, I don’t fear death, I fear not dying. It’s weakness and helplessness I want to avoid. And mental decline. It’s death in life I don’t want. Of course, that may be what God gives me. The possibility makes me really feel that my life is not my own. It’s God’s, and he may want me to live through something I absolutely do not want. So if my life’s his then, I need to live like it’s his now. But I don’t like the idea.

Is there an American Catholic way of death?

Priests tell me that for Catholics today the death of a loved one is something to get through, without much help from the Church. They’ll want a memorial service and a burial, of course. But not a funeral Mass. Even if grandpa planned out his funeral Mass in detail, they’ll tell the priest that grandpa wouldn’t want them to have to deal with all that when they’re in mourning, so just forget it.

It used to be that even Catholics who rarely went to Mass at least had their children baptized and had a funeral Mass for their parents, and made sure they got last rites before they died. Now the main people involved seem to be the doctors, the funeral directors, and whoever helps with the memorial party. The priest is another functionary and the least important one.

I’ve seen this in some Catholics I know. The Church is part of their culture, but not part of their lives. They give up all the help the Church would give them. And the hope. It’s sad.

Grief is inevitable as we age. Is there a practical way to prepare for it?

You can prepare for it, but the preparation may not do you much good. When a loved one dies, he’s dead for the rest of your life. Your life has a hole that will never be filled.

It’s one of the great things about Christianity, that it understands and affirms our suffering now, while telling us that the loss we feel will someday be healed. Our faith doesn’t pretend death doesn’t hurt. It comforts us by telling us it won’t hurt forever.

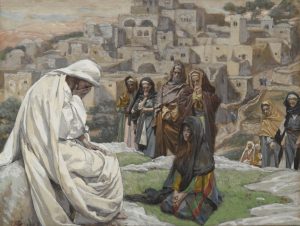

Jesus cried at the tomb of his friend. He knew Lazarus would rise again. In fact, he knew he was going to raise Lazarus in a few minutes. Still, he cried. Because death hurts. It should not be.

But you can keep short accounts, as my granddad said. Love them in every way you can. Ask for forgiveness if you hurt them. Forgive when they hurt you, even when they don’t ask. Know that you’re going to lose them and that you might lose them without warning. Don’t let anything come between you.

Pray for them so your prayers for them dead will continue the friendship you had with them alive. For us, dead just means alive somewhere else.

What do you make of the current “memento mori” (“remember you must die”) trend in fashion and social media? What drives it?

I’m not sure. One reason would be demographics. Baby boomers are beginning to die in significant numbers and they drive a lot of our culture. And when boomers die, their children and grandchildren suddenly have to face death, which they may not have done before.

After marriage and the birth of our children, the thing that most changed my life was my dad’s death. I was close to him and suddenly he was gone. I was prepared for it, and still the world got instantly emptier and lonelier. I’d thought about death, but as a theoretical matter. Suddenly I felt how much death hurts. I’m guessing that many younger people are having the same experience.

I don’t mean this dismissively, but it’s easier to be interested in death when you’re young, and a lot of people who are into “memento mori” seem to be in their 20s and 30s. Younger people seem to find death interesting, partly because it’s not real for them. I was like that.

It’s a final subject, and makes you look at ultimate things, but that’s easy to do when it’s not likely to be final for you for decades.

And maybe many feel a kind of helplessness my generation didn’t feel. You have a world at war, until recently a bad economy, a sexual economy that’s caused huge damage, lots of abortions, which do the same thing. People might think seriously about death, because their lives have elements of death in them.

The world tells you to “eat, drink, and be merry, because it’s fun,” as I said. Death is the thing that tells you that life is serious, because it ends. And that’s hopeful, because it tells you that your life matters.

What are the practical effects of a keener awareness of mortality — our own and others’?

It depends on who you are and what you believe. To people who don’t believe in God, death says live for today. That can mean hard partying or enjoying being wicked or just being a decent person or investing yourself in the future through your kids, or maybe through your work or your art.

Probably for most, if they think about death, they think they should do good, because it’s good to do good. So kind of mediocrity.

Death tells Christians to live for God and for others, because someday you’ll be dead. You’re training yourself to be someone who wants heaven or someone who doesn’t.

How do we prepare for death without becoming morbid or weird?

Live well. Grow in holiness. The old adventure stories got it right when the hero said, “Prepare to meet your maker.” If you do that because you love God, because you want to sanctify this moment because it’s his, you don’t need to get morbid or weird thinking about death.

You don’t have to think about it at all. You can, if it helps you work harder to love God and others. But even that doesn’t have to be morbid. It can be like planning for a long trip. I want to get there, so while I’m here I need to do this, that, and the other thing. All very practical.

Catholics don’t deny the pain of death. But we can also be very matter-of-fact about it.

What resources do we find in Catholic tradition that are unavailable elsewhere?

The Mass as a sacrifice for the dead. That’s the big one. The communion of saints and our relation to the dead, praying for them, earning indulgences for them, and so on. That’s almost as big a resource.

The Church tells us that no one is beyond reach. She gives us stuff to do for them and what should be a lively sense of the connection to them. She helps us feel that the loss is temporary. They’re the immigrants who’ve sailed to the New World. We’ll keep going here and join them when we can.

Euthanasia promises a “happy death.” What is a happy death in reality?

One in which you know that, as St. Paul said, “I have fought the good fight … I have kept the faith.” One in which you rest in God’s love for you and for everyone you’re leaving behind. “With no regrets,” as they say in romantic comedies.

Basically, you want to die as a saint. If not a saint, someone who looks forward to being purged and refined through God’s love in purgatory. But dying as a saint is better.