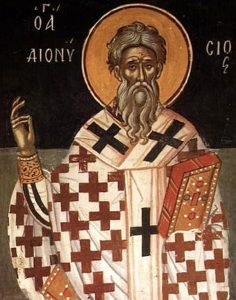

It was the great misfortune of St. Denis to serve as bishop of Alexandria, Egypt, in the years A.D. 248-264.

They were the worst of times. Everyone agreed on that point. They were years of simultaneous pandemic, war, economic collapse, and persecution.

The Roman Empire was in disarray, and government at every level was unstable. In just one year of St. Denis’s episcopacy, two Roman emperors were murdered by their own troops.

To top it off, the earth was suffering sudden, disruptive climate change, which had a ruinous effect on crops.

But St. Denis managed to thrive in the midst of it all — every crisis, calamity, and catastrophe. For this, history remembers him as Denis (or Dionysius) the Great, and he earned the title.

Alexandria, St. Denis’ birthplace, was the second city and intellectual capital of the empire. It was home to antiquity’s greatest library. It was a center of scientific research and technological innovation. As a harbor city, it was also a commercial hub and strategic military position.

St. Denis was born there, around 190, to a family that observed the traditional religion, worshiping an array of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian gods. Their city was especially devoted to the god Serapis and the goddess Isis.

St. Denis converted to Christianity as a young man and studied in Alexandria’s renowned catechetical school. His teacher was Origen, one of the great Scripture scholars of the ancient world.

When Origen was forced to flee the city in 216, a man named Heraclas took over the school. When Heraclas was elected bishop, St. Denis assumed leadership — and he continued in that office even after he himself succeeded Heraclas as bishop in 248.

Within a year after St. Denis became bishop, hell broke loose upon his corner of the earth.

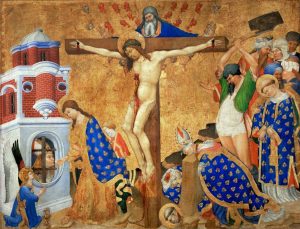

Always prone to riots, the city’s mobs turned to lynching Christians and invading their homes. Many believers died rather than utter blasphemies against Jesus Christ. The practice of Christianity had been illegal since the first century (though rarely punished), and the local authorities considered the Faith a nuisance at best, and so the mobs went unpunished.

During that first calamity, others arose.

It’s likely that the climate fluctuations came first. There was, throughout Europe and the Middle East, widespread cooling in temperatures, which brought about drought and crop failures. For several years the Nile River failed to flood, leaving farmers’ fields infertile throughout Egypt.

The strange weather had no known precedent. Some people feared that the earth was entering its decrepit old age. “The summer sun burns less bright over the fields of grain,” wrote one observer. “The temperance of spring is no longer for rejoicing, and the ripening fruit does not hang from autumn trees.”

For St. Denis’ already struggling congregation, the economic fallout was ruinous.

What’s more, this global cooling — with resulting malnutrition — may have been the necessary precondition for the next great catastrophe to hit Alexandria: the pandemic of 250.

Historians debate the viral cause of the plague that year. It was likely a novel influenza virus or hemorrhagic fever. It spread rapidly through the empire and quickly reduced the population of the known world by a third. The equivalent number of deaths today would be 2.5 billion.

Densely populated Alexandria was hit particularly hard.

In dire circumstances, people tended to blame their leaders. Their leaders in turn looked for scapegoats. The Roman Emperor Decius focused all the blame in the world upon the Christian Church and its members.

The natural disasters, he explained, represented the vengeance of the old gods. The idols were angered because, with the growth of Christianity, so few people offered them sacrifice. So in January 250 Decius issued an edict requiring every citizen of the empire to offer sacrifice to the old gods.

The edict renewed the rage of the persecution already in progress in Alexandria. Its enforcement was swift. St. Denis lamented that the number of Alexandrian martyrs included “men and women, both young men and old, both maidens and aged matrons, both soldiers and private citizens — every class and every age.”

But not every Christian showed courage. Alongside his account of the martyrs, St. Denis reported that he had also seen crowds of believers racing to abandon the faith, running “eagerly towards the altars, affirming by their forwardness that they had not been Christians.”

Yet the disease continued to spread, which drove the persecutors to greater fury.

After all the defections and executions — and the pandemic and famine — the Church in Alexandria found itself with drastically reduced congregations and almost no clergy. In the great city St. Denis presided with four remaining priests.

And the little flock soon began again to attract new converts. The medical historian William McNeill argues that the pandemic played to the Church’s strength.

He writes: “One advantage Christians had over their pagan contemporaries was that care of the sick, even in time of pestilence, was for them a recognized religious duty. When all normal services break down, quite elementary nursing will greatly reduce mortality. Simple provision of food and water, for instance, will allow persons who are temporarily too weak to cope for themselves to recover instead of perishing miserably. Moreover, those who survived with the help of such nursing were likely to feel gratitude and a warm sense of solidarity with those who had saved their lives.”

McNeill concludes: “The effect of [the] disastrous epidemic, therefore, was to strengthen Christian churches at a time when most other institutions were being discredited.”

In a similar way, the martyrs, by their steadfastness, gave public testimony to the value of life in Jesus Christ. That was what they desired more than anything else on earth, even bodily life.

St. Denis managed to outlive the worst of the pandemic. He also outlived Emperor Decius. And he even enjoyed a brief respite from persecution at the beginning of the reign of Emperor Valerian. In time, the Nile returned to its cycle of flooding, and the land responded with abundant produce.

Yet the old bishop knew that any peace in this world would be temporary.

Nonetheless, he expressed hope for his Church. And he held on to hope because he saw that Christians everywhere had been purified by the crises. For a while at least they had drawn together in common efforts, and shown what a unified Church could accomplish.

He wrote: “But know now, my brethren, that all the churches throughout the East and beyond, which formerly were divided, have become united. And all the bishops everywhere are of one mind, and rejoice greatly in the peace which has come beyond expectation.”

Now in 2020, as we enter our “new normal,” can we, too, hope to see a peace beyond our expectations? History suggests we can.