“I quit for almost two years and got sucked back in … just went to confession and I’m ready to try this again.”

“Prayers are appreciated tonight. Spent a half-hour in prayer while crying over the struggle and a failed relationship.”

“Lord Jesus, scourged for my sins of impurity, have mercy on me.”

“Praying my rosary today for anyone trying to #BreakTheChains of pornography.”

All of these quotes come from — believe it or not — the social network Twitter. What they all have in common is that they end with or include the recently trending hashtag #BreakTheChains.

Twitter is often seen as a vortex of name-calling and backbiting, but Father Cassidy Stinson decided to use it for something entirely different: a prayer campaign. On July 27, the newly ordained priest based in Williamsburg, Virginia, posted a thread of tweets to launch the campaign.

“Hey. We need to talk about something,” wrote Stinson. “Pornography. I knew this before I became a priest, but now it’s become all the more clear to me that this is an absolute scourge for so, so many of us, spiritually and psychologically.”

The thread later added, “I think we need to be praying FOR everyone currently suffering from the addictions and habits of using pornography — and for everyone caught in that industry.”

Then came the inaugural hashtag: “I’ll be sharing my own daily prayers to #BreakTheChains of pornography, and I’d love for you to join me.”

The thread received more than 1,000 likes, almost 200 retweets, and dozens of comments. And since then, the hashtag has spread through Twitter, producing hundreds of prayer requests, shared stories, and supportive exchanges. Stinson himself declined a request for an interview for this story.

“I remember seeing Father Cassidy’s first tweet about #BreakTheChains and just feeling really pumped about joining the prayer campaign,” Carlos Germosen, a seminarian in the Archdiocese of New York, told Angelus News. “I was amazed by how fast it grew, and how many people stepped up to the plate and joined in on the prayer.”

Olivia Vollmar was also inspired by Stinson’s tweets. The day he posted his first #BreakTheChains thread, she posted her own thread that shared her story about struggling with pornography and masturbation. “I lived in a secret world of sin for such a long time,” she wrote via email.

The big, bad porn problem

Campaign such as Stinson’s are up against a billion-dollar industry that is rapidly growing and instantly available to millions of people. According to a 2016 national survey, 27 percent of people ages 25 to 30 first viewed pornography before puberty, and 64 percent of people ages 13 to 24 look for pornography at least every week.

Also in 2016, the internet’s most popular pornography site alone drew people to watch 4.6 billion hours of pornography, and 61 percent of those visits were on a smartphone. What used to be only accessible by covertly buying pornographic magazines from a store — an endeavor that might require plenty of planning and excuses — is now at just about anyone’s fingertips, and often for free.

What’s more, that content has far surpassed the realm of Playboy magazine. Eighty-eight percent of scenes in some of the most popular pornographic films contain physical aggression, and 49 percent contain verbal aggression. Eighty-seven percent of that violence was directed at women.

“People are carrying portable X-rated movie theaters in their pockets that can also make phone calls,” said Catholic author and speaker Matt Fradd in a phone interview with Angelus News.

The rampant use of this technology has brought a tidal wave of psychological, physiological, and emotional harm upon many of its users. Damages include addiction, fertility problems, increased risk of sexually transmitted infections, and negative perception of one’s body.

Five states have declared pornography a public health issue. On top of that, pornography has been shown to contribute to marital infidelity and separation. One study has found that 56 percent of divorce cases involved one spouse using pornography.

Even if not discussed publicly, the issue seems to be a frequent subject in the confessional nowadays.

Father Steve Newton, CSC, a priest at the University of Notre Dame, said that “most young people, especially young men, are at least exposed to pornography during their developing years. Estimates suggest 90 percent, and my experience in dealing with the population group would uphold those estimates.”

Several older priests who spoke to Angelus News agreed that while chastity has always been one of the most commonly raised struggles brought up in the confessional, the last 10 to 15 years have seen an increased number of penitents — young and old, male and female — confessing the sin of pornography during the sacrament of reconciliation.

The Church’s challenge

If pornography is a big problem in our culture, the Catholic Church has been anything but isolated from that problem.

“The number of our Catholic clergy who struggle with this problem is very unsettling,” Archbishop Charles Chaput told Catholic News Agency in 2015, during the Synod on the Family.

Some might also recall how Michael S. Rose’s book “Goodbye, Good Men,” published right around the 2002 clerical abuse scandals broke, revealed how shockingly pervasive pornography was at some Catholic seminaries.

“People are carrying portable X-rated movie theaters in their pockets that can also make phone calls,” Catholic author and speaker Matt Fradd told @AngelusNews. Share on X

Also in 2015, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops released a document addressing the massive problem in the United States. “The damage it causes to oneself, one’s relationships, society, and the Body of Christ needs healing,” the bishops wrote. “Pornography can never be justified and is always wrong.”

But apart from affecting members of the Church itself, pornography also makes it more difficult for people to absorb the Church’s message, said Fradd. “In St. Bonaventure’s ‘Journey of the Mind to God,’ he writes about how sin bends man over on himself, like a cripple. Because of this, he is unable to see God, himself, or others.”

Fradd is the author of “The Porn Myth” (2017), and launched the free online course STRIVE to help men stop using pornography. At its core, he said, pornography is “a blatant lie about what the human person is and is for.”

So, amid all the problems, where’s the hope?

Finding healing

In its 2015 document, the USCCB emphasized the Church’s mission to be a “field hospital,” as Pope Francis has put it, to those in need. “The Church as a field hospital is called to proclaim the truth of the human person in love,” the document states, “to protect people — especially children — from pornography, and to provide the Lord’s mercy and healing for those wounded by pornography.”

Many say they’ve found the Church to be just that: a “field hospital” that offers the best prescriptions for healing what may seem like incurable wounds.

“Honestly, what can be found only here [in the Catholic Church] is the grace and healing that come from the sacraments, especially the sacrament of confession,” Germosen said. “For someone who is struggling with an addiction to pornography, it is often liberating to hear ‘I absolve you’ after falling to a temptation. It lifts the burden and guilt of the sin off of your shoulders.”

Vollmar, who is currently in the process of converting to Catholicism, described how she looks forward to receiving that same sacrament.

“I know there is so much grace and healing within that and I’m looking forward to finally confessing and being absolved of this sin,” she said.

In the meantime, she added, “The absolute biggest healing factor for me and my addiction has been eucharistic adoration. I've been going weekly (when I am able) and it has been such a grace. There is something so special about spending time with Jesus that changes things.”

At the same time, Newton stressed that for many people, part of this battle has fallen out of their control. “Addiction is not sin,” he told Angelus. “It is illness. As such, it needs to be treated by a trained professional.” In addition to confession, Newton points those struggling with addiction to “seek professional help if they find they cannot quit on their own.”

Given that several states and organizations have identified pornography as a public health issue, medical attention remains essential. Still, some have found that the Faith brings healing that cannot be found elsewhere. According to Fradd, “the teaching of the Church on sexuality is very much what the world needs.

“Just like you would expect someone who knows what the human body is and how it works to give you better advice, if the Church is who it claims to be, [it knows] what the human person is and how to act in line with reality and therefore [be] fully alive.”

Fighting the good fight

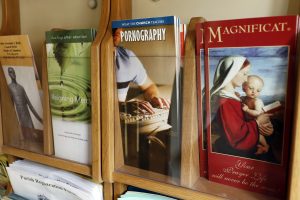

While the Church’s doctrine and sacraments as sources of healing have always been available since its foundation 20 centuries ago, there seems to be a sense that pornography is still a “secret” sin, too shameful to be brought to light, much less openly challenged. But several organizations, both Christian and secular, are working to change that.

One such example was the University of Notre Dame, where a group of students petitioned the administration to implement a filter on the campus Wi-Fi to block pornographic sites. After several articles, events, meetings, and a fair amount of media attention, the university denied the request.

Veronica Maska, co-president of the student group that led the campaign, says that providing students easy access to pornography not only perpetuates a humanitarian crisis but also violates the school’s mission.

“As a Catholic university, Notre Dame has a moral prerogative not to be complicit in the base degradation of human dignity that pornography portrays and encourages,” she said.

But the denial has not stalled the students’ efforts. “Our club’s goal this year is to continue the campus conversation on the filter and capitalize on the national momentum our effort has created,” Maska continued.

The group is bringing several speakers to campus to address the issue, including Matt Fradd, and will be encouraging students to “self-filter” by installing porn-blocking settings on their mobile devices.

Though the campaign at Notre Dame has not resulted in an actual campus Wi-Fi filter yet, it has contributed to more successful outcomes at other campuses. This past year, the Catholic University of America and the University of Dallas student governments have both voted to block porn. Several initiatives are underway at other schools, Catholic and non-Catholic alike.

Where do we go from here?

The expansion of campaigns, programs, and research might offer some hope in the face of the massive problems pornography creates, but according to Fradd, the way forward may depend just as much on individual attitudes as it does on widespread initiatives.

“We need to come alongside people, really love people and not shame them,” he said. “I’ve heard evangelization defined as one better telling another beggar where the bread is. We’re all broken.”

“For someone who is struggling with an addiction to pornography, it is often liberating to hear ‘I absolve you’ after falling to a temptation. It lifts the burden and guilt of the sin off of your shoulders.” Share on X

For Alvaro de Vicente, the headmaster of an all-boys school in Montgomery County, Maryland, preventive measures are just as important, and for that, parents play a crucial role. A simple first step, though shocking to some, is to consider not giving your adolescent a smartphone.

“Smartphones prey on teenagers’ curiosity by providing them with instant access to whatever information they want to get or video they want to watch,” de Vicente wrote in a letter to parents last spring.

In a phone interview with Angelus News, he said that this letter (as well as another one he wrote back in 2008) came as “a response to growing concern” about the risks of technology, including pornography.

“The primary battle [with technology] is for the freedom of the students,” he said. “What can we do to help the students remain free as they grow up and help them make moral decisions?”

De Vicente finds that setting guidelines that make it easier for young people to detach from technology is a smart strategy for winning that battle. At his school, for instance, all high school students (except seniors) must turn in their phones to the office before the first class and retrieve them after the last class. Third- through eighth-graders may not bring them to school at all.

When it comes to recommending filtering technology to parents, de Vicente said that while he does not always recommend one in particular, he finds that Covenant Eyes has a smart approach.

“The filter helps avoid accidental viewing of compromising sites,” he said, “and the accountability system engages the freedom of the individual to avoid searching for that material, while at the same time setting up a conversation with the partner.” Germosen also mentioned Covenant Eyes, as well as VictoryApp by LifeTeen.

Whether or not school policies, university petitions, or Twitter prayer campaigns produce immediate or radical change, what they have done is spark conversations that, perhaps for many, were previously almost impossible to begin.

For Vollmar, sustaining those conversations is the best way to help remedy the crisis. “So many people ... think they are all alone in this battle,” she said. “If we take away the power of secrecy, it is more easily beaten.”