William King knew he wanted to be a priest since he was 4 years old.

He traces the decision to one of his childhood priests, Father Greg Chisholm, a Jesuit who once served as pastor of Holy Name of Jesus Church in Jefferson Park. Like King, Chisholm is African American, and seeing him in this role planted the idea that he, too, could become a priest someday.

When King was in high school, another African American priest, Father Allan Roberts, the late pastor of St. Bernadette Church, took him under his wing and nurtured this vocation.

King, 22, aspired to be like them — strong preachers, personable and good caretakers of their parishes — and their presence proved to him that priesthood was a viable path for African Americans. So after graduating high school in 2015, he entered Juan Diego House, a seminary for men aiming to become priests for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

“It made a huge impact to know that black men like myself could be in a role that’s predominantly seen as white or Latino — and that I could do it well,” he said.

But his experience is not the norm. Many black men in Los Angeles have never known an African American priest, and vocation stories like King’s are becoming increasingly rare.

The Archdiocese of Los Angeles — the nation’s most diverse Catholic diocese, where worship and ministry happen in more than 40 languages — has ordained only one U.S.-born African American priest in its 82-year history.

Roberts, King’s mentor, became the first African American priest ordained by the archdiocese in 1980, but since his death in 2016, Los Angeles has had no African American diocesan priests.

While black priests have served in the city as part of religious orders, and African-born priests have headed diocesan parishes, Los Angeles has long been missing African American priests to minister to the estimated 150,000 black Catholics in the area.

“It’s the reality of many of our dioceses,” said Father Stephen Thorne, a priest with the National Black Catholic Congress. “I believe that God has called black men to the priesthood in the Catholic Church, so it’s not about the call. It’s that we have not done our best to recruit them and to sustain that vocation.”

The underrepresentation of African Americans in the priesthood is nothing new, said Matthew Cressler, author of the 2017 book, “Authentically Black and Truly Catholic.”

Even though Catholics of African descent have been in the Americas “for as long as there have been Catholics in the Americas,” he said, the Church has long resisted their presence in the clergy.

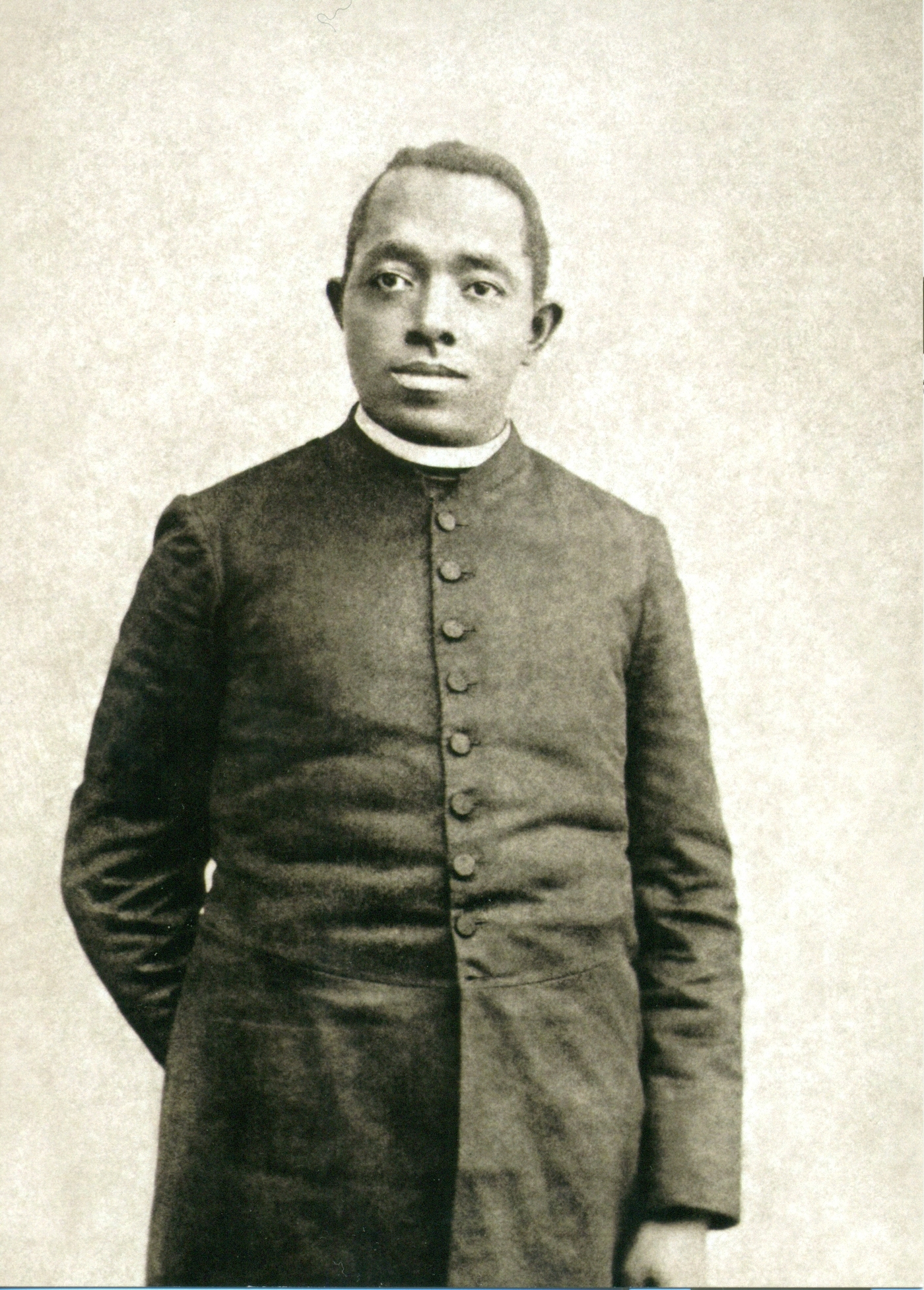

The first priests of African descent in the U.S. passed for white, and it wasn’t until 1886 that the U.S. had an openly black priest. Even then, it wasn’t because American Catholics had accepted racial equality in the clergy.

Augustus Tolton — who was born to enslaved parents — applied to seminaries across the country with the help of an Irish priest he had been studying with in Illinois, said Cressler. But no seminary would accept him because he was black, so he instead had to study in Rome, where he was eventually ordained. (Tolton’s cause for sainthood is now in process.)

“The institutional Church for the majority of its history has acted as most white-dominated institutions did, which is that they barred ordination, education, and even encouraging of black vocations,” said Cressler, who is also an assistant professor of religious studies at the College of Charleston in South Carolina.

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that black priests were ordained in larger numbers in the U.S., Cressler said. But many black men still faced significant obstacles to get there, including harassment and hostility from fellow seminarians.

Others were diverted away from diocesan seminaries and toward missionary orders that catered specifically to African Americans, such as the Society of the Divine Word and St. Joseph’s Society of the Sacred Heart — a process Cressler called a “siloing of black vocations.”

And when the United States faced a priest shortage, Cressler said, many churches brought in priests from the Global South. So while African American vocations remain low, the number of African-born priests has risen.

Today, of the 3 million African American Catholics living in the United States, only eight are active bishops, 250 are priests, and 75 are seminarians in formation for the priesthood, according to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

“We are still reckoning with the inheritances of this long tradition where, for most of its history in the United States — really up until the last half-century or so — the Catholic Church was recognized to be the providence of the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of European immigrants,” Cressler said.

This history of discrimination is not so easily undone, said Anderson Shaw, director of the African American Catholic Center for Evangelization in Los Angeles, and is one reason that so few African Americans are part of the clergy today.

“There wasn’t a family that didn’t know someone who tried to get into seminary and was turned away by white folks,” he said of the Jim Crow era. “When someone was treated poorly, families developed an attitude that was passed down generations that you don’t want your son to go through that, so they haven’t encouraged them to become priests.”

Even if African Americans do enter seminary, it’s not always an easy path. Deacon Mark Race, of Transfiguration Church in Leimert Park, called it a form of culture shock.

When he applied to seminary, he was asked why he wanted to be a deacon.

“I remember saying that I wanted to be a deacon so that I could come back to my community, represent the archdiocese and show an African American face as clergy,” he said. “And I was told point-blank that you’re not being ordained for your community — you’re being ordained for the diocese. Initially that was hard to swallow.”

In addition, he said, the style of worship he had grown up with wasn’t taught at seminary.

“They’re not singing your songs, they’re not praying your prayers, they’re not preaching the way you preach, they’re not doing anything the way you learned it,” he said.

“What you’re bringing almost has to be strained out of you so that you can learn what’s called the ‘proper’ way of worshipping, the ‘proper’ way for liturgy, the ‘proper’ way for doing things,” he went on. “It’s a whole new type of learning. So it’s difficult, especially for a young man who’s been in the African American community his whole life.”

King, who entered seminary in 2015, agreed. Several of his fellow seminarians told him that they didn’t like the African American style of worship — singing, dancing, call, and response — or that it was liturgically incorrect.

“If we trace our Christian roots, we know that it started with different people in different villages in their homes, celebrating the Eucharist in different languages,” he said. “So why can’t African Americans worship and celebrate how they feel comfortable?”

Father Samuel Ward, vocations director for the archdiocese, said these types of incidents show “unfamiliarity and ignorance” with African American culture.

“When people say, ‘We don’t do Gospel here,’ it’s just because you haven’t done it here before,” he said. “And that’s different from a dogmatic law of ‘No, we can’t.’ ”

But for many African American men, these dynamics can be a deterrent to entering the seminary, said King. He was able to endure these challenges with the support of a network of black priests across the country.

His mentor, Roberts, died during his first year at Juan Diego House, so he had to look beyond Los Angeles for guidance from other African American priests who understood what he was going through.

“Having them in my corner really gave me a sense of hope,” he said.

But these and other incidents weighed on King, and a year-and-a-half into his formation he decided to leave. It was a combination of factors, he said — personal, spiritual, academic — as well as a realization that the seminary was no longer a good fit for his goals. So in 2016 he withdrew from Juan Diego House.

King was the archdiocese’s only African American seminarian, and today it has none.

The impact of not having a single African American priest belonging to the archdiocese is profound, black Catholic leaders in Los Angeles said.

For Shaw, it means less visibility and an inability to advocate for the community at higher levels of the Church.

“It’s not easy to do the things that you really need to do, especially when you’re dealing with the hierarchy of the Church and the Church deals specifically with those folks who are like them,” said Shaw.

“Bishops deal with priests, priests deal with other priests. Lay people are brought in whenever the decisions have already been made. If you’re part of that decision-making role, things could be changed — at least you’d have a voice.”

“But we have no voice,” he said.

The absence of African American priests also hurts vocations, said Race.

“It’s important to be able to serve at Mass from the altar, to be able to sit up there and have young people look at you and say, ‘You know what, that’s something that I can do,’ ” said Deacon Mark. “Because if you never see anybody from your background doing it, you never feel that that’s something you can do. You just never aspire to it — and that’s the problem.”

It may also lead to African Americans not relating to their parish priests.

“It’s important that there’s somebody there who knows your history from a personal point of view, not from what they’ve read or heard,” Race said, “but that they personally understand what the people have gone through and can connect and speak to their pain.”

Greg Warner, who heads the southwest division of the Knights of Peter Claver and Ladies Auxiliary, an African American Catholic lay organization, agreed, adding that if the Church can’t connect to African Americans, they may end up leaving the Church.

“The dynamics of the world have changed so that they need to talk to somebody about what’s going on, and with Caucasian priests or anybody else, they don’t feel like they relate to them,” he said.

“I think that for a lot of parishioners, that’s why they leave the Church. They go to nondenominational churches where they have African Americans and they feel more comfortable there and more wanted.”

Oscar Pratt, the music director at Transfiguration Church who previously served as principal of Transfiguration Elementary School, said it also affects the youth. He once took his students on a field trip where they saw photographs of African American nuns.

“I remember the girls saying, ‘Wow, the nun, she’s black!’ ” Pratt said. “I was stunned. I said, ‘My God, my students have never seen an African-American nun.’ ”

Pratt, whose son is a priest in Boston, said that because there is so little black clergy in the archdiocese, he relied on books, magazines, and photographs to tell his students the story of African American Catholics. But it was no substitute for seeing people from their own community in positions of religious leadership.

“I’ve felt that they would be proud of the fact that there were African American nuns, that there were African American priests,” Pratt said. “It may not increase the vocation count, but I know for a fact that it would improve their self-image.”

Solving the African American priest shortage will require efforts from both the community and the archdiocese, leaders said.

For Race, the first step is recognizing — and honoring — African American culture throughout the archdiocese. While the archdiocese has successfully integrated dozens of languages into its Masses, African Americans — who speak English — are often overlooked as having a distinct culture, he said.

“If you go to almost any Mass, especially at the cathedral, there’s going to be some part of the liturgy or the readings that’s done in Spanish,” he said. “But how do you accommodate the African American culture when we speak English?”

Another thing Race said he’d like to see is the establishment of a task force to open up communication between the archdiocese and the African American community.

“The African American community needs to be in very close contact with the people who are making the decisions and the seminary to say, ‘Why is it that we can’t get a young man ordained?’ ” he said. “ ‘What are you looking for so we can work with our own community and explain to them that these are the practices, these are the rules, this is what’s necessary, this is what they’re looking for in a man who is going to be a priest?’ ”

(Ward said these talks are now underway, and so that he can “see what concrete steps we might be able to take.”)

A model for how such a task force might operate is in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which established an Office for Black Catholics in 1979, and recently launched a campaign aimed at recruiting young men and women into religious life. The archdiocese currently has three African American diocesan priests and one seminarian.

Father Richard N. Owens, Philadelphia’s director of the Office for Black Catholics, said the new initiative identifies young African American men who might be interested in the priesthood, and hosts a series of events to provide them support and educate the broader community about the history of Catholicism in the African American community.

The campaign is also raising money to provide financial assistance to young men going through seminary, and works with the seminaries to host multicultural Masses so that all men in formation are exposed to a black Catholic style of worship. The task force is also a source of support and mentoring if any issues of racism do arise.

“When you’re the only minority in a predominantly Caucasian community, there are structural issues that you may face being the only one,” Owens said. “And you’ll need to have a support structure of people helping you when you face racism.”

After King left the seminary in 2016, he started working for a stained-glass artist who creates windows for churches and hospitals in Los Angeles. The experience broadened his horizons and brought him closer to God, he said.

But stepping away from seminary also made clear to him that he needed to return.

So last year he re-applied and was accepted into seminary — but not to a seminary with the archdiocese. Instead, he is now with St. Joseph’s Society of the Sacred Heart — commonly known as the Josephites — a nationwide religious order that specifically ministers to African Americans.

By joining the Josephites, he said, he’s guaranteed to serve African Americans and to help revive the black Catholic community — missions he said he feels called to do.

“Pope Paul VI said to the sons and daughters of Africa, ‘Give your gifts of blackness to the Church,’ on one of his papal visits,” he said. “We’re trying to give our gifts of blackness to the church — our roots, our heritage, our culture, our way of worship.”

But it also means leaving Los Angeles. In January, King moved to Washington, D.C., to attend St. Joseph’s Seminary. After ordination, he could be sent anywhere in the country.

Wherever he goes, he hopes to promote vocations among fellow African Americans, because he knows the influence an African American priest can have.