“Do you think I could be a saint like St. Thérèse of Lisieux?” — Servant of God Charlene Richard

You know you’re deep in Catholic territory when not only is there a church and a grotto named after Our Lady of Lourdes, but the college football team knocks heads at Our Lady of Lourdes Stadium.

This is Lafayette, Louisiana, deep country spiced with gumbo, accordion-and-fiddle zydeco music and crawfish fields, all leavened with Cajun devotion to the “One True Church.” French immigrants carried the Faith (and not much else) here in the mid-18th century after expulsion from Canadian territory on the Atlantic coast known as Acadia.

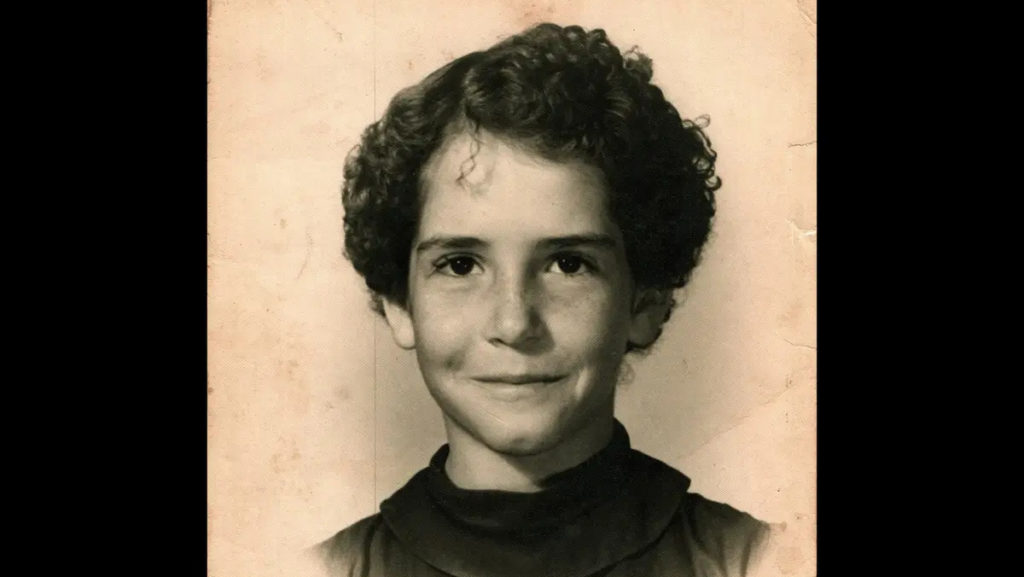

A few miles south of the stadium, the sick and dying receive succor at Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center. Back when it was called a hospital, a 12-year-old named Charlene Marie Richard died there of acute leukemia in August 1959.

One of 10 children of Joseph Elvin Richard, a sharecropper, and his wife, Mary Alice, a home nurse, Charlene was a bright and friendly girl. She captained the girls’ basketball team and stood up to bullies.

The Richards spoke French at home (English was for school), and, in addition to summertime watermelon parties and horseback riding, socialized by going house-to-house praying the rosary. They received the Eucharist at St. Edward Church, a wooden World War II-era church near a stand of oak trees.

“Every night we’d all kneel to say the rosary,” said Charlene’s brother, 78-year-old John Dale Richard, a retired nurse. “On the table, there’d be a crucifix, a statue of Our Lady and the Bible. Charlene would pick flowers for the table, roses and azaleas.”

Charlene’s agony lasted two weeks from diagnosis to death. In her final days, the girl who wished to emulate St. Thérèse of the Little Flower offered her suffering to God for the healing of others and conversions to the faith she held dear.

She did so with the same sincerity and cheer for which she was known at home, on the playground, and dancing to early rock ’n’ roll in her socks in the living room, resting between songs by Little Richard and Elvis with a glass of Kool-Aid.

On her deathbed, she told her confessor — a newly ordained priest named Father Joseph F. Brennan [1931-2017] — that she’d carry a message for him.

“Father Brennan told Charlene that a beautiful lady was going to visit her,” said John. “Charlene said, ‘I know, and I’ll tell her Father Brennan says ‘Hi.’ ”

Otherwise unexplainable events began upon Charlene’s passing and have continued for the past 60 years, putting her on a long path to possibly being declared a saint by the Catholic Church.

“Her influence was immediate. Mom began getting letters right away asking for prayers,” said John, oldest of the Richard siblings, four born after Charlene’s death, seven still alive.

“A woman in the room next to hers was very sick and refused to meet with the priest. Charlene prayed for her. After Charlene died, they moved her into her room. The woman returned to the Church.”

A room at the Diocese of Lafayette’s offices holds more than 1,600 testimonials of miracles attributed to Charlene’s intercession. On the 30th anniversary of her death in 1989, chairs had to be set up on the church grounds to accommodate the more than 4,000 people who showed up for a memorial Mass.

For decades, some 10,000 people have been visiting her grave each year, hoping that their petitions will be added to the files. In 2020, Bishop John Douglas Deshotel of Lafayette officially opened the local phase of her cause for beatification, which declares a person "blessed" — the final step before canonization, or sainthood. The next year, the U.S. bishops voted to lend their official support for its advancement.

Nanette Reiners is president of the Charlene Richard Foundation in Lafayette. “Our priests have a few more people to interview,” she said. “Then we can close out her cause on the diocesan level and send it to Rome. Maybe by October.”

Earlier this year, my friend Charley Allen and I were welcomed by John and his wife, Lorita, into their home on Feb. 11, the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes. This was not by design — at least not ours.

A native of the Pelican State and longtime LA resident, Charley attends St. Mark Church in Venice, where he serves on the parish council and volunteers with the food pantry. His son Murphey is an altar server.

A 1995 graduate of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Charley hadn’t been back to southwest Louisiana in nearly 25 years. Prior to our trip — from New Orleans to Charlene’s grave and back in his father-in-law’s pickup truck — he’d not heard of “the Little Cajun Saint.”

Before The New York Times magazine ran a lengthy feature on Charlene last December, few outside of Louisiana knew about her death from lymphocytic leukemia and what the Times headline called a “Miraculous Life and Afterlife.”

That includes Caroline Meyer of Waterloo, Ontario, who called John out of the blue — “I get at least one call every other day,” he said — while Charley and I enjoyed coffee and cake that Lorita made from figs grown in the yard.

A nonpracticing Catholic, Caroline, 42, was diagnosed with cancer in 2020. She was in remission before it returned two years later and is now terminal. Her trip to Charlene’s grave on Valentine’s Day came a day before an appointment at the Anderson Cancer Center in Houston to consider alternative treatments.

After reading the Times article, Caroline told her husband, “I’m feeling drawn to this, I have to go.” She contacted the foundation and was put in touch with John, who met her in the churchyard with Lorita.

As nearly always, other pilgrims were there seeking Charlene’s help with problems physical, emotional, and spiritual.

“One woman was waiting to hear if she had cancer and a gentleman there was being treated for cancer. We all spoke French,” said Caroline, an attorney raised in Quebec by a Haitian-born mother.

The visit, she said, was “a peaceful experience that helped me come to terms with my diagnosis. I got a sense that I was on the right track, that wherever the path leads, it’s going to be OK.”

Charlene is buried nine miles from her brother’s home in the tiny hamlet of Richard, named for the family’s 18th-century ancestors, the clan listed among the first four documented families that arrived from Acadia in 1764.

John and his siblings were present when a postulator for the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints, Argentine priest Father Luis F. Escalante, conducted an exhumation in December 2021.

They were accompanied by gravediggers, a medical examiner, and the local sheriff to keep away the curious when Charlene’s wooden, water-damaged coffin was brought up. The body was taken into the church hall and laid upon altar linen to be worked on.

On the Richards' dining room table — just inches from our coffee cups — was a clump of her hair that the medical examiner had clipped and given to John. Lorita, who’d gone to elementary school with Charlene, washed it and zipped it in a plastic bag.

Also, a chip of a bone from a finger encased in glass (one of many “relics” that will be preserved from her fingers), the crucifix she held in the hospital, a few medals and the scapular she was buried with, and a handful of loose white beads from a rosary entwined in her hands.

Asked if witnessing the exhumation was difficult, John said it was and it wasn’t. As the postulator worked, he and his siblings prayed the rosary in French outside of the room. Memories of her last days can be more troubling. For about nine hours during her hospitalization, which followed complaints of joint pain and, for reasons unknown, radiation by a previous doctor, Charlene asked to see her brothers and sisters for the last time.

“They brought her home in a wheelchair with oxygen and was able to hold her godson on her lap before she went back,” he said, pausing to catch his breath.

“Wow,” he whispered, tearing up briefly. “It was the first time I heard Daddy cry, a wail from his heart. I was 14 and it was so strange to me. He kind of hit the bottle for a while, Mama eventually snapped out of it.”

Each time he tells the story, he said, “it’s all real again. It never goes away.”

That afternoon, Charley and I accompanied the Richards to Saturday afternoon Mass at St. Edward, where the couple was married in 1964. The current building replaced the old wooden one with the first Mass celebrated on Thanksgiving Day 1963, the same week that President John F. Kennedy was murdered in Dallas.

Much of the $66,000 cost to build the stone church, according to parish history, came from solicitations by the pastor at the time, Father Floyd Calais, in Charlene’s name. One check came from Floyd Patterson, a former world heavyweight champion boxer who converted to Catholicism in 1952. Now 96, Father Calais still prays to Charlene daily.

On our visit, the Eucharist was celebrated by the pastor, Father Korey LaVergne, who said the extended St. Edward community “already knows she’s a saint. It now depends on official human testimony.”

Charley and I walked to a corner of the cemetery where a wooden kneeler adorned with a rosary and an illustration of Charlene’s face is stationed at the base of the grave. It was a cold, gray day in early February and the sun was beginning to set. Charley kneeled and I walked slowly through the churchyard saying the rosary, offering beads for Charlene’s intercession with the Blessed Mother and her Son for a loved one battling cancer back home in Baltimore.

Like Caroline, Charley “felt this call, this pull, a strong emotional feeling.” It was he who had old family friends in nearby Mowata that put us in touch with John and Lorita. The sensation, he said, was far more than nostalgia.

Louisianans like Charlene and those who love her, he said, “are my people, humble people who literally live off the land. I grew up visiting them in the summers, we boiled crawfish and played in the fields. It gave me a sense of coming home.”

Like me — along with Caroline from Ontario and a local agricultural pilot named Larry Matte waiting his turn at the kneeler — Charley offered prayers for the defeat of cancer: in his case, the mother of a good friend in Los Angeles.

“I never felt I had a reason to pray to Charlene until my wife got sick,” said Larry, 72, who remembers when “old-timers” — volunteers — mowed the grass in the graveyard.

Later, Charley recalled that halfway through the Mass, he felt a sudden pang of guilt upon realizing he hadn’t even thought of Charlene once during the service. In silence, he apologized to her. Then he felt something.

“The feeling that came to me was so intense, she was smiling and said, ‘You were thinking about Jesus and that’s why I brought you here.’”

He asked Charlene to take his prayers for his friend’s mother to God and, he said, received this reply in spirit: “I will, but I don’t know what he’ll say.”

Now and then, said John, he dreams about growing up with Charlene and the others in their childhood house that stood, before it was moved, behind the one where he lives now. Sometimes, the dreams are about the games he and his brothers and sisters invented to pass long days out of school.

“We’d make altars out of old potato crates and dress up in grass sacks for [cassocks],” he said. “If I was the priest, my brother Dean was the bishop. If I was the bishop, Dean had to be the pope.

“Sometimes we’d play hospital in the barn and if one of our patients died, we’d have a funeral,” he said. “We’d put the kid who played the dead person on a plank and play Mass. I was usually the priest and Charlene would read the Gospel. She was the most extraordinary ordinary person I’ve ever known.”

Back when the Richard kids put on religious skits to amuse themselves, Charlene — already a devotee of St. Thérèse, the Little Flower of France who died of tuberculosis at age 24 — asked her grandmother if one day she might be a saint, too.

Of course, John remembers their grandmother answering. Charlene replied that she wasn’t capable of great things.

“Then do the best you can.”

“I can do that,” said Charlene.