Tom Hanks has brought the beloved Fred Rogers to major motion picture screens this holiday season. What is it about his tenderness we seem to long for? What is it about his model for caring for children and one another that we need to recapture?

Erica Komisar is a psychoanalyst in New York City and author of “Being There: Why Prioritizing Motherhood in the First Three Years Matters.” In recent weeks, she’s written powerfully about Fred Rogers, political correctness, and the faith of children as a columnist for the Wall Street Journal.

Angelus contributing editor Kathryn Jean Lopez asked her some questions about parenting, nostalgia, and what our renewed interest in Mr. Rogers in 2019 might promise for the future.

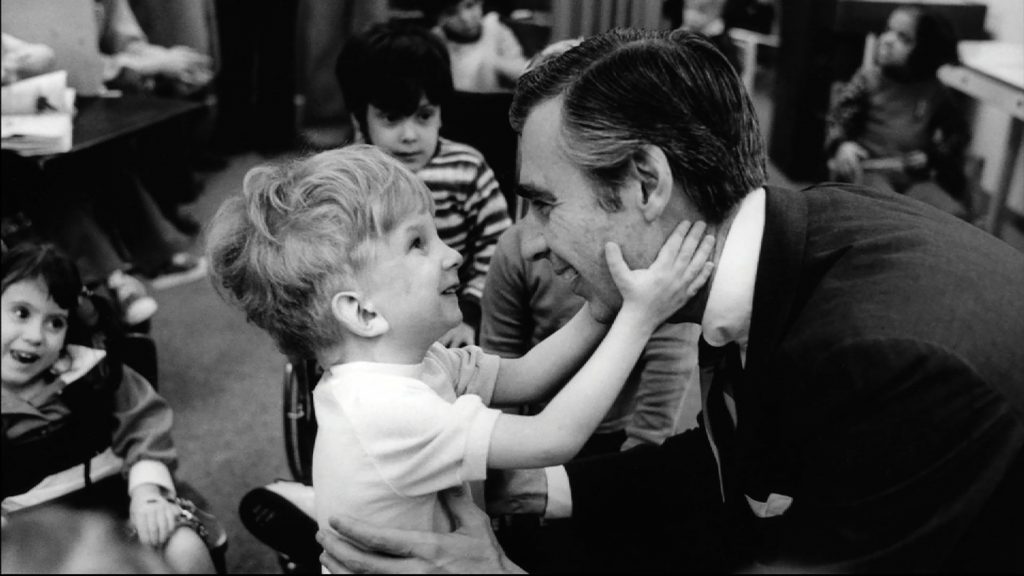

Kathryn Jean Lopez: In your op-ed for the Wall Street Journal on Fred Rogers and children, you wrote, “Rogers rejected the old-fashioned idea that children are to be seen and not heard. He believed adults should lead them with love and understanding, not fear and punishment. Children are delicate human beings, emotionally sensitive and neurologically fragile. To develop emotional and mental health, they need respect and tenderness — the freedom to express all their feelings and the security of being acknowledged by the adults who care for them.”

How can we ever restore/renew/create (Which is it? All of the above?) a culture where children are considered treasures?

Erica Komisar: It would be incorrect to say that the past is something to idealize in terms of parenting. Many mothers did stay home, fathers and mothers attended their children’s sports events and there was more of a physical presence of family in children’s lives in the past.

However, there was also a great deal of emotional insensitivity, repression of emotion, and treating children as if they were to be seen and not heard. Parents did not necessarily value children as separate individuals who had a great deal to offer.

Fred Rogers became a model for sensitivity and empathy toward children at a time when parents were still spanking children and not engaging them emotionally or valuing their individual voices.

The new model is one of not just loving our children, but understanding them; not just spending more time with them physically, but showing up emotionally; valuing what they feel and what they say; showing interest in them as people not just for what they achieve. So we are, in fact, creating a new model of parenting.

Lopez: What is behind our Mr. Rogers nostalgia? Is it some widespread desire for a time when we had some basic agreement on some fundamentals when it comes to gender, identity, purpose, even common decency?

Komisar: Nostalgia over Fred Rogers is really recognition of his incredible contribution to parenting and child development and our understanding of how to raise healthy children. He was really the first public figure to respect children and childhood and to connect the way we treat our children to their mental health and personality development.

I think many adults are longing for and wishing they had parents who were as emotionally attuned and sensitive as Mr. Rogers. There is so much pain in adults due to insensitivity and neglect in their own childhood. Nostalgia is not necessarily wishing for something we had, rather something we wish we had and never had.

Lopez: How can Mr. Rogers help us, besides teaching us to slow down and be kinder? Is there some kind of transformational shift that is begging to happen?

Komisar: Mr. Rogers advocated kindness and empathy toward all human beings. He was a minister as well as a TV personality. His goal was to get adults to recognize that we are all valuable and lovable in the eyes of God. Children do not need to do anything special or achieve great things to be valuable or loved. This is a message that we need desperately today.

Lopez: I’m guessing you did not title your other recent Wall Street Journal piece “Don’t Believe in God? Lie to Your Children.” But what is it about faking it that you want to relay as a parental responsibility?

Komisar: No, you are correct, I did not give my piece its title.

However, I do say in the piece, if you do not believe in God or heaven, you have to come up with a believable story to reassure your children. That is a white lie if you do not believe in God and heaven.

But, from a child development perspective, children cannot cope with the finality of death. It is far too frightening to tell your young child that they are dust when they die. They need to have hope and a belief that loss is not final.

Without that hope, they may become frightened and anxious about the future and ultimate losses. For believers it is not lying. But for nonbelievers it is a white lie, which protects the fragile psyches of their children and perhaps encourages them to rethink their own beliefs.

Lopez: Why is faith so important to children, family life and, we often read, even our health?

Komisar: Faith or belief in magical things we cannot see or touch is important to children. From early childhood, imagination and imaginary play is a way that children work through their conflicts and cope with frustration and loss. Fantasy is critical for social emotional development.

Faith or belief in a nurturing, loving God or higher power who you can turn to in hard times helps children to cope with adversity and loneliness. Think of it as a nurturing parental support that you can summon up anytime and anywhere you may need it. The ability to reach inside and find that source of strength and security is supportive in hard times, and we all have hard times.

Faith also provides children with hope and a path forward in a stressful and sometimes overwhelming and competitive world. Hope is not something we can see or touch. It is not something tangible or concrete. Like the belief in God and heaven it is something that helps us to go on and look forward, to be optimistic about the future.

Lopez: Is there something you would like faith communities to appreciate about this more? About how they present themselves as communities and individuals?

Komisar: Parents are models for children when it comes to faith. When parents have faith, get joy from their beliefs, and instill empathy, gratitude, and hope through those beliefs, their children will follow. Not immediately (particularly in adolescence when teens need to rebel), but eventually.

If parents do not push too hard and do not punish their children for temporarily rejecting their faith, chickens will come home to roost. If, however, parents feel rejected, get angry, and retaliate when their children reject religion, they may win the battle but will not win the war.

Structure, but with a lighter touch, is always best for children. The best way to teach your children is by modeling how faith enriches your own lives as parents.

Lopez: How does Mr. Rogers help with faith? Is it impossible to understand him without it?

Komisar: Mr. Rogers was a minister and a man of faith, and though he did not advertise that in his TV show, he enacted all of the values of a man who believed in the goodness of all human beings. His sensitivity, empathy, acceptance of others, and belief in the intrinsic value of all children was an expression of his religious beliefs. It would be impossible to separate the man from his beliefs.

Lopez: Is there something especially important for people to understand about family and parenting today?

Komisar: Your children need you more than you think they do. That does not mean you have to be there every second, nor does it mean you should become a hovering, intrusive, or anxious parent.

What it does mean is that we have gotten our priorities all wrong. Time is a barometer of what we value. If you spend only 90 minutes per day with your child and work 10 hours per day, then work is your priority.

The question I ask parents is not, “Do you love your children?” because the answer for the most part is “Yes.” The question I ask parents is, “Are you really interested in your child or childhood? Do you enjoy just being with them and playing with them?”

If the answer is “Not so much,” then I know I have a good deal of work to do with that parent to understand the pain that adult experienced as a child whose own parents were not interested in spending time with them.

Our children need our time, but more importantly they need us to be interested in them above all things, and they know when we are not. They know when they are not our priority, and it is incredibly painful to children.

Lopez: Nothing we’re talking about here is ideological or partisan. Do you have any hope for common ground on some of these things? That maybe this new movie and the positive public impression of Mr. Rogers bears hope for something better for our politics and culture, including social media, and lives?

Komisar: Understanding and acceptance of differences and kindness toward one another is what is missing today. We are more similar than we are different. It is not until we can see many perspectives that we can bring communities together.

We share basic human values and have similar goals as humans: to feel understood, to be acknowledged, to be accepted, and to live with our universal needs of freedom, health, dignity, and safety met.

Our common humanity is greater than our differences.