Now that I’ve entered my 40s, I have been taking a sincere, careful look at the woman I’ve become and the areas in which I still want to grow and heal. On my last birthday, I couldn’t help but think, “I thought I’d have control of my worrying by now.”

It’s a battle I’ve been waging for as long as I can remember.

I’ve written elsewhere in these pages that my default mindset is one of anxiety. I am constantly anticipating people’s needs for fear of failing them, and I regularly put together contingency plans for any number of “what if” scenarios.

I’ve heard plenty of theories as to why: genetics (my family tree is filled with other anxious apples); I was separated from my parents several times for major surgeries before the age of 2, so I’m hardwired to look for control; I’m a millennial woman, and while we were told we could have it all, the price tag was perfectionism.

There are some upsides to having an overactive mind: it’s been a boon for writing, as I am constantly mining my everyday experiences for meaning and connections. It has also helped me to run a few communications offices and now a busy home with three boys aged 5 and under.

The downsides are obvious: periodic insomnia, constantly making lists, being so preoccupied with the future that I miss what’s happening in the present moment.

As a Catholic, I know that Our Lord desires my freedom from worry and fear. I’ve read more times than I can count Jesus’ famous admonition:

“Can any of you by worrying add a single moment to your life-span? Why are you anxious about clothes? Learn from the way the wildflowers grow. They do not work or spin. But I tell you that not even Solomon in all his splendor was clothed like one of them. If God so clothes the grass of the field, which grows today and is thrown into the oven tomorrow, will he not much more provide for you, O you of little faith?” (Matthew 6:27–30).

I have always struggled with the tension between sincerely believing in God’s provision but also struggling with worry. It’s easy to feel shame, as if I should be able to pray it all away.

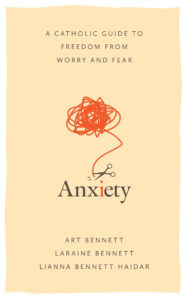

That is, until I picked up “Anxiety: A Catholic Guide to Freedom from Worry and Fear” (Sophia Institute Press, $19.95). Written by clinical therapists Art and Laraine Bennett and their daughter Lianna Bennett Haidar, the book is aimed at helping Catholics make sense of the rise of anxiety disorders in light of science and faith.

“Anxiety” acknowledges physiological and psychological realities, how it squares with Scripture and Tradition, and provides hands-on steps and tools to retrain your brain and break troublesome patterns of thought and behavior.

The book is not a substitute for professional help. But the authors’ clinical background, in combination with their Catholic faith, means that they have a command of the science of anxiety and where we can find the lasting peace we’re all looking for in Christ.

The Bennetts and Haidar note that chronic anxiety and anxiety disorders have been on the rise, even before COVID-19. This type of anxiety is defined as “excessive worry or fear that occurs more days than not for six months.” Its telltale markers include restlessness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and muscle tension.

While we all inherited a fight or flight response from our ancestors (this is what taught them to run from the saber-toothed tiger), today our amygdalas, the part of the brain responsible for stress response, are firing on all cylinders even when the circumstances don’t merit it.

In someone with chronic anxiety, the amygdala sets off an alarm about a possible future threat, not an immediate one.

The Bennetts and Haidar offer three options for those dealing with chronic fear: 1) do nothing and continue to worry about worrying; 2) try to avoid the anxiety, eliminating and disconnecting from anything or anyone that makes you nervous; 3) face your anxiety head on while assessing your triggers with the rational part of your brain.

The book is about the third option. One of the first things the authors recommend is to locate anxiety in the body where it’s felt. Most often, patients will point to their chest, where their heart is racing and their breathing is labored. That’s because the amygdala increases adrenaline and cortisol in the face of a perceived threat.

Once anxiety is located, it can be directly faced. This is a tactic supported by another Catholic in the field, Dr. Kevin Majeres, host of the Optimal Work podcast and faculty member of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Majeres encourages his listeners and patients to “lean in” to anxiety.

“Reframing [anxiety] as a helpful burst of adrenaline can be used as an opportunity to learn to train one’s own amygdala to respond in more appropriate ways,” he’s said.

The authors encourage the same. If someone approaches anxiety with curiosity, asking, “I wonder how I’m feeling right now?” he can put some space between his anxiety and thoughts. This means that they can shrink the amygdala and strengthen the prefrontal cortex, or the rational part of their brain.

The authors also believe that no matter the reason someone has a temperament or disposition toward worry, no one is ever predestined or locked into that mode of thinking. The ability to grow in virtue with the help of grace is part of being a Christian.

One key to growth is also examining one’s coping mechanisms. While we need not be called to avoid all earthly attachments like the Desert Fathers, it’s important to ask ourselves questions like, “What’s the difference between having a glass of wine and using wine to escape?” or whether we depend on entertainment too much out of fear of being alone.

When one decides to face fear where and when it hits — to pause, assess the threat level, examine it with curiosity, and put together a rational plan to move forward — that becomes the healthy way to cope and manage. Otherwise, the amygdala will keep growing and keep firing at inappropriate times, because it’s allowed to.

The authors round out their advice with the well-known strategy of reframing. While it’s easy to look at situations in a negative light, they encourage their patients and readers to ask, “How might God look at this situation?” This can immediately expand one’s perspective and allow someone to identify a situation as an opportunity for growth and sanctification.

Does Jesus want us to worry? Certainly not. But does he understand it? Of course.

Quoting a commentator’s examination of anxiety in the work of Hans Urs Von Balthasar, the authors share “...God does not come to abolish anxiety” but rather, in solidarity with those of us who suffer, “transforms anxiety by giving humanity a perspective and orientation for overcoming it.”

“Anxiety” is the first book of its kind for Catholics who are managing chronic worry and fear, providing a holistic look at the reality that “God has created us so that, as embodied souls made in His image and likeness, we have brains possessing the capacity within to heal and restore mental health.”

For the first time in a long time, I have a plan for my next birthday assessment, and it’s hopeful.