Armenian Christianity has been in the news. Cameras flashed in October as Kim Kardashian West, wife of Kanye, took her children to Armenia to be baptized in her ancestral church. In 2015 the Getty Museum in Los Angeles settled a multimillion-dollar lawsuit brought by the Armenian Apostolic Church for “restitution of cultural heritage looted as a result of the Armenian Genocide.”

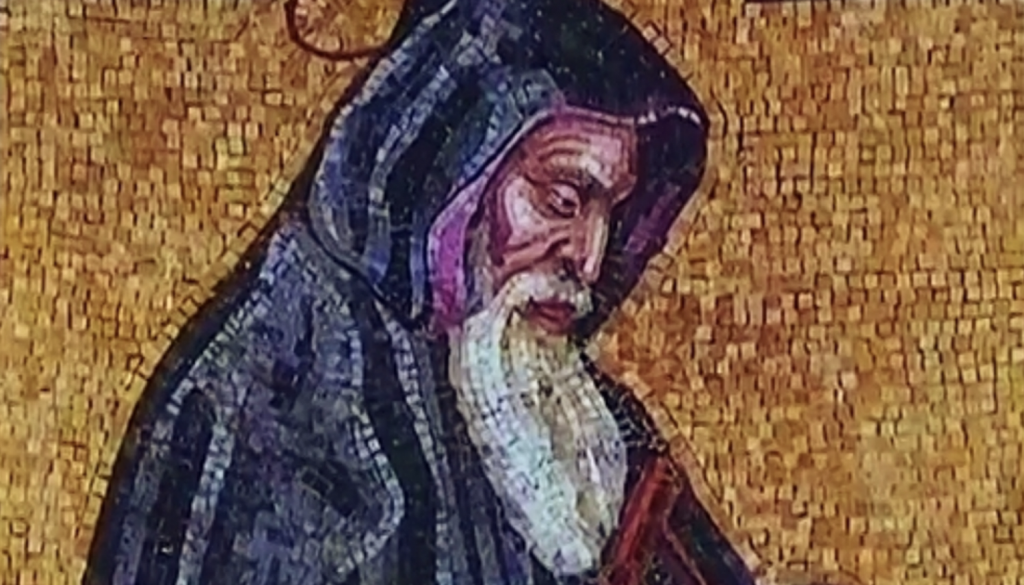

But the biggest story got little media attention when it broke. Pope Francis, in 2015, designated St. Gregory of Narek, a 10th-century Armenian, as a “doctor of the Church,” an elite group of 36 saints renowned for their teaching.

The news arrived to great celebration in Southern California, which is home to the world’s largest population of Armenians outside Armenia. But St. Gregory was, and remains, largely unknown outside Armenian circles.

Michael Papazian, Ph.D., intends to remedy that. A professor of philosophy at Berry College in Georgia, he has produced a book that introduces this great saint to the world beyond Armenia: “The Doctor of Mercy: The Sacred Treasures of St. Gregory of Narek” (Liturgical Press, $40).

He spoke with Angelus News.

Mike Aquilina: Most Catholics were unaware of St. Gregory until the pope numbered him among the doctors. Why is that?

Michael Papazian: Mainly because Gregory was Armenian and for a variety of reasons — historical, linguistic, political, geographic — the Armenian Christian tradition has not received attention outside Armenian circles.

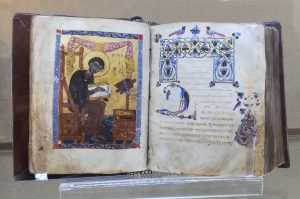

Gregory was writing in a language that’s distantly related to most European languages, but with its own alphabet and other unique features. Translation of his works into modern languages is a relatively recent phenomenon, so an English reader wouldn’t have had access.

Also, Armenia is a small country, easily overlooked. I grew up in New Jersey, which has a large Armenian community, but whenever I told people my name is Armenian, I would get puzzled questions like, “What’s that? Is that like Romania?”

Among Armenians, however, Gregory is well-known and loved. If we were to go to a pious Armenian family’s house, we would find at least two books: the Bible and Gregory’s great collection of prayers, the “Book of Lamentation.” His prayers are in our liturgy. There’s popular devotion to him. I’m aware personally of many healings and miracles attributed to his intercession.

I’m thrilled that Gregory now is receiving attention. This all began with St. Pope John Paul II, who cited Gregory often. The pope and Gregory shared a profound devotion to the Blessed Virgin.

Aquilina: How would you describe his work? What makes it deserving of a title reserved for the best of the best?

Papazian: I have a hard time describing it. It’s so different from writings of other theologians. Some have compared him to St. Augustine. Others have said that he’s Armenia’s version of Dante. Neither comparison gets us very far.

His style is reminiscent of St. Ephrem, the great fourth-century Syriac doctor, and I think there may be some direct influence there. His writing, even when it’s not, strictly speaking, poetry, is always poetic. He loves to experiment. He invents words and constantly makes allusions to biblical passages.

I sometimes think that he’s what you’d get if you crossed Augustine and James Joyce. But his spirituality is also infused with the simple piety of the Desert Fathers; and, although he lived before him, there’s an element of St. Francis in him, too. He’s a synthesis of so many strands of Christian tradition.

We expect a doctor not just to teach orthodox doctrine, but also to have an especially profound understanding of Scripture and the faith. Gregory clearly meets these criteria. He is, as Pope Francis has stated, “an extraordinary interpreter of the human soul.” He presents a striking portrait of the extent of human sinfulness and our utter dependence on God.

He also has a beautiful vision of the essential role of the Virgin in the economy of salvation, and affirms that she was immaculate from the beginning of her life. He does all this with extraordinary grace and humility.

Aquilina: Why do you call Gregory “The Doctor of Mercy”?

Papazian: I was reluctant. Not because it doesn’t fit, but because it seemed presumptuous of me — a layperson with no formal theological education — to bestow a title on a doctor! But so many doctors have titles — Augustine is the “Doctor of Grace,” for example — so it seemed fitting that Gregory have one, too.

The overarching theme of Gregory’s theology is God’s infinite mercy. The “Book of Lamentation” is a work of penance and reconciliation. But penance and contrition are useless without God’s mercy and forgiveness. The parable of the prodigal son recurs throughout Gregory’s writings. The figure of the father who always welcomes us no matter how far we have strayed is central to Gregory’s understanding of God. It also did not seem a coincidence that Pope Francis named Gregory a doctor on the Sunday of Divine Mercy in 2015.

Aquilina: “Mercy” is, of course, one of the major themes of Pope Francis’ pontificate. Does this make Gregory particularly suited to our time?

Papazian: Yes. There is the theme of mercy, but also the theme of the Church going to the peripheries. Gregory is a saint of the peripheries, living on the margins of the West and on the frontier of Christendom, a priest of a Church that has often been isolated from the mainstream.

As a saint venerated by both Catholic and Orthodox Armenians, he is a symbol of Christian unity and hope for the healing of all divisions that separate humanity.

Aquilina: What is distinctive about Armenian Christianity? How does it enrich the Catholic Church?

Papazian: Armenians have adopted so many of the practices and rituals of other Christian traditions. In the book I describe two major influences on the Armenian rite: Byzantine and Syriac. But also there has been an openness to the West. We see this in the liturgy and the vestments of our priests.

The liturgy of the Armenian Church has many of the features of the old Roman rite. This was not a result of forced “Latinization,” but an organic development. The paradox of Armenian Christianity is that such a small, often insular, and perpetually persecuted Church has shown remarkable openness and hospitality to other traditions.

The Armenian tradition can serve as an inspiration to the Universal Church in our path toward recovery of full communion.

Aquilina: Gregory was dismissed as a heretic by some in the West, even after he was named a doctor of the Church. What was that all about?

Papazian: Today we have an Armenian Catholic Church, in full communion with the bishop of Rome, and the Armenian Apostolic Church, one of the non-Chalcedonian churches that we call Oriental Orthodox now. The division is the result of disagreements about the two-nature Christology affirmed at the Council of Chalcedon in the fifth century.

The Armenian Apostolic Church has never agreed to Chalcedon and has maintained a one-nature Christology that nevertheless recognizes Christ as perfect God and perfect man, but in one nature rather than two.

Gregory recognizes as orthodox both the Chalcedonian two-nature Christology and the Armenian one-nature Christology. He adopts a conciliatory stance: He rarely if ever uses the term “nature,” but simply affirms the perfect divinity and humanity of the one person of Christ.

Remarkably, that Christological stance is exactly the one that was affirmed in the common declaration by John Paul II and the Armenian Apostolic Catholicos (or supreme patriarch) Karekin I in 1996, the declaration that many observers believe put an end to the Christological disputes between the two churches. So while Gregory was a priest of a church separated from Rome, he always taught what is now confirmed as orthodox doctrine.

Aquilina: What are the lessons of his life and work for today?

Papazian: One of the most moving passages in the “Book of Lamentation” is Gregory’s prayer of forgiveness for those he has hurt. In my inadequate translation, it reads:

“Now what prayers in this book may be pleasing to you,

What smoke of incense acceptable to you shall I offer,

O Christ, praised heavenly King,

If I do not pray to you to bless those whom I cursed,

Tend to those I have bruised,

Care for those I have alienated,

Give refuge to those I have betrayed,

And heal the souls of those I have wounded in body?”

As we learn how many of those entrusted with authority both in the Church and outside have abused their position and wounded those entrusted to their care, I think this confessional prayer of Gregory is especially timely and should be on all our lips and minds.