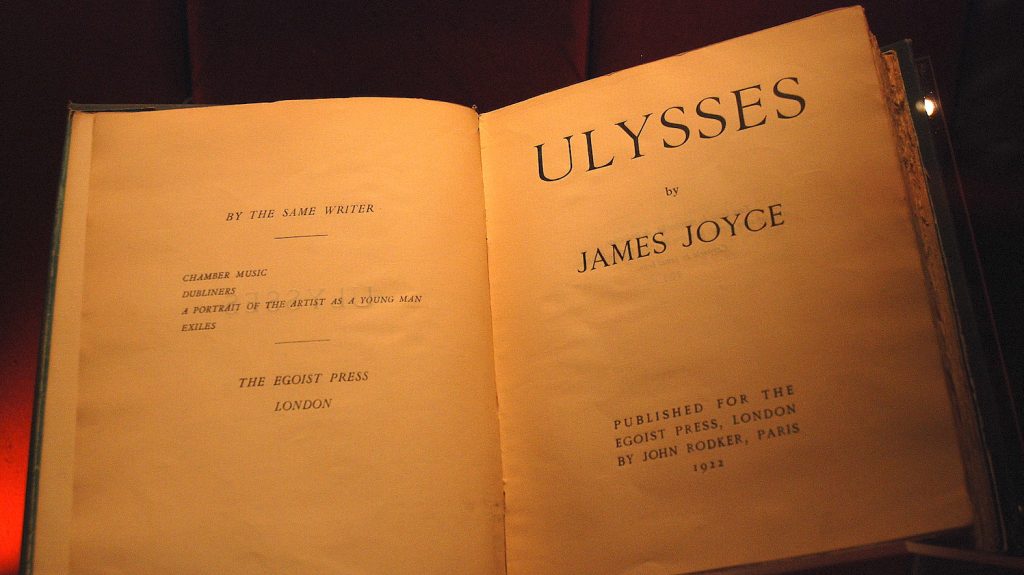

Mark Twain said that a classic is something everyone wants to have read, but no one wants to read. One hundred years ago, James Joyce published “Ulysses,” a novel generally recognized as a classic of 20th-century literature. It is also famously difficult to read.

I had been planning to read “Ulysses” ever since a groom whose marriage I was minister for gave it to me as a gift. The man, non-Catholic and agnostic, but friendly and interested in Catholic things, taught English at the American School in El Salvador. He thought I would like it. I brought his gift back to the States with me and for 10 years I would look at it on my bookshelf and think of him and his wife, who tragically died very young.

I decided to read it over the Labor Day weekend to mark the centennial anniversary of its publication. My friend thought I would like it because of the many Catholic references in the book. And there certainly are very many: The first page has a man echoing the Tridentine Mass; one of the protagonists, a thrice-baptized Jew named Leopold Bloom, goes to a Catholic Mass and speculates incorrectly that the symbol IHS on the priest’s vestments mean, “I have sinned. No, I have suffered.” The text is punctuated with Latin phrases slyly quoted.

Although the book is famously modeled on Homer and abounds with references to Greek heroes and gods, Joyce is also unremitting in his biblical allusions. Old Testament figures are dropped in conversation: Esau, Moses, David, the Queen of Sheba, Elijah, Ahab. Psalms are quoted in Latin and English. New Testament references and phrases pepper the dialogue, which is often blasphemous. Even seminarians would have to look up Joyce’s historical illustrations, about heresiarchs like Sabellius and Arius, and need translation of Thomas Aquinas’ Latin. Many a Catholic student from years ago would reasonably smile at his line, “It was a nun, they say, who invented barbed wire.”

Joyce said he wanted the novel to be a moral history of his country, concentrating on Dublin, its capital city, and the “centre of paralysis.” It is a book about many things, but especially about death, grief, and faith (and the lack thereof). In its first pages, Buck Mulligan accuses Stephen Dedalus (the hero of “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” and a stand-in for the author) of having killed his own mother because as she lay dying, he refused to kneel and pray as she asked him. Refusing to pray when your mother asks you from her deathbed? I was more shocked at this than at some of the more sordid parts of the book.

Initially, Joyce is only reporting Dedalus’ refusal to pray. Later in the book, the author is shamelessly sacrilegious. The grief motif is associated with religion when Dedalus imagines the ghost of his mother worrying about his soul. The irreligious son banishes the vision, but there is a “doth protest too much” element in Joyce’s routine anti-clericalism and apostasy. He could never get over what he rejected, despite all his vulgar and scatological attempts at outrageous rebellion.

Virginia Woolf famously called “Ulysses” “a misfire,” said it was pretentious, and “underbred, not only in the obvious sense, but in the literary sense.” Joyce’s incontinent prose in the work, so different from his earlier “Dubliners” and “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” makes it hard for even those who might be sympathetic with his anti-religious ideas to appreciate “Ulysses.” Several years ago GQ published an article entitled, “We read Ulysses so you don’t have to.” It is a hilarious summary and parody of what is, in my opinion “The Emperor’s New Clothes” of literary masterpieces.

As I slogged through the almost 1,000-page book, it was only my goal to have read it that kept me going. Yet I found the last section of the novel to be the most difficult to get through. I don’t know what was worse: the gross and ignorant vulgarity of Molly Bloom’s stream of consciousness, or the self-indulgence of a writer who scribbles a 60-page run-on sentence.

There is no accounting for taste, but sometimes there should be some kind of reckoning. American Nobel Prize winner Sinclair Lewis once said that Joyce was “a little insane.” I am surprised at his unusual resort to understatement.

The experience of reading “Ulysses” will be only worth it for me if I can help others not to make the same mistake. I thought I was going to fill a gap in my literary knowledge and culture. To the contrary of Mark Twain’s joke, I would say that “Ulysses” is a classic I would have rather not have read.