Adam gazes out the car window as his mom pulls up to his new school: a manicured lawn, a prominent statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and a crowd of students in neatly pressed uniforms.

Adam shifts in his seat. “But I’m not even Catholic…” he mumbles. Neither is his mom, nor are they interested in St. Agatha’s Catholic education per se.

But that’s not why they’re there. As his mom has reminded him, “This is your last chance.”

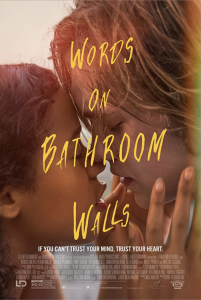

As the upcoming film “Words on Bathroom Walls” unfolds, viewers learn why Adam (Charlie Plummer) and his family are so desperate to make St. Agatha’s work. Adam battles schizophrenia, a chronic mental condition that causes him to hear voices and see figures that are not actually there. The LD Entertainment and Roadside Attractions film, out this Friday, unveils how Adam navigates his condition amid high school and family conflict in order to reach his dream of going to culinary school and becoming a real chef.

The 111-minute drama showcases a host of winner traits: special effects that pull us into the storm within Adam’s brain, a polished script packed with quips and conversations to ponder, and an engaging plot with layers of romance and action. But one of its most striking qualities is that without being a religious film, it teaches a powerful lesson about faith.

St. Agatha’s might serve only as the backdrop to Adam’s story, but it generates two significant and unabashedly Catholic characters: Sister Catherine (Beth Grant) and Father Patrick (Andy Garcia). Both characters are open about their faith, but the contrast between their relationships with Adam paint very different pictures of Catholicism. From them, viewers receive a portrayal of how to (and how not to) convey the faith to those in difficult situations.

We first meet Sister Catherine. She is a small, thin woman with piercing eyes and careworn hands. Though not intimidating, she oozes severity. In her first meeting with Adam and his family, Sister Catherine touts the mission of St. Agatha’s, emphasizing the moral integrity it holds dear. She enumerates the conditions under which Adam can stay enrolled: He must keep up his grades, follow school rules, and provide regular confirmation that he is maintaining clinical care for his condition. And she makes it clear that she will not hesitate to dismiss Adam if he fails to keep up his end of the bargain.

Nothing is necessarily wrong with Sister Catherine’s standards. After all, running a prestigious Catholic high school requires setting a high bar. But for all her commitment to the straight and narrow, Sister Catherine remains a distant, harsh figure. It’s no wonder that when Adam first meets her, his schizophrenia conjures a wall of flame erupting around her desk as she speaks.

Contrast that with Father Patrick, a pudgy priest with a knowing smile and gentle voice. Adam first meets him in the confessional, which he uses more as a refuge than a sacrament, given that he has very little understanding of how reconciliation works. But from that first encounter onward, Father Patrick displays a quality that sets him apart from Sister Catherine: he listens.

In the confessional, though Adam can’t receive the sacrament, Father Patrick encourages him to use the time as he would like, and he lets him speak candidly. What’s more, though he has a very different perspective on life, he remains attentive and empathizes with Adam’s questions and complaints. (When Adam vents, “You wouldn’t want your mom reading your diary, would you?” Father Patrick offers an amused smile and emphatic “No.”)

Both Sister Catherine and Father Patrick are committed to their mission of guiding the students who pass through their school. Neither directly contradicts Church teaching, nor do they question each other’s authority. But where one places more emphasis on the external rules and appearances, the other focuses on quiet conversations in hopes of uplifting a downtrodden heart. And that makes all the difference for Adam when it comes to deciding whose message to harken.

In a 2016 homily, Pope Francis declared, “God is proclaimed through the encounter between persons, with care for their history and their journey. Because the Lord is not an idea, but a living person.” In “Words,” Father Patrick embodies this message of the pope, which is the message of the Catholic Church: that evangelization can only be truly effective when it is grounded in charity.

In each of his conversations with Adam, Father Patrick speaks the truth of the Gospel, but he never lectures at Adam, nor does he cast judgment on him for his mistakes or lack of knowledge about faith and morals. He is simply a listening ear, ready to offer consolation or a prayer whenever needed.

Even when he doesn’t have the right words on-hand, Father Patrick takes time to ponder a better approach, seeks Adam out, and shares what he’s learned from their discussion. By truly listening, he not only offers Adam a source of love and truth, but he also opens himself up to grow more in his faith and ability to communicate it well. As a result, he models wisdom and humility together, a union of virtues that is difficult yet essential for any Christian to spread the Gospel.

Father Patrick and Sister Catherine might play secondary roles in “Words,” but their presence speaks volumes about what true empathy and evangelization mean, and what they do not. Any viewer inclined to learn not just about schizophrenia but also about the best Christian response to it would find a powerful answer in this film.

“Words on Bathroom Walls” is scheduled for release in theaters nationwide Aug. 21.