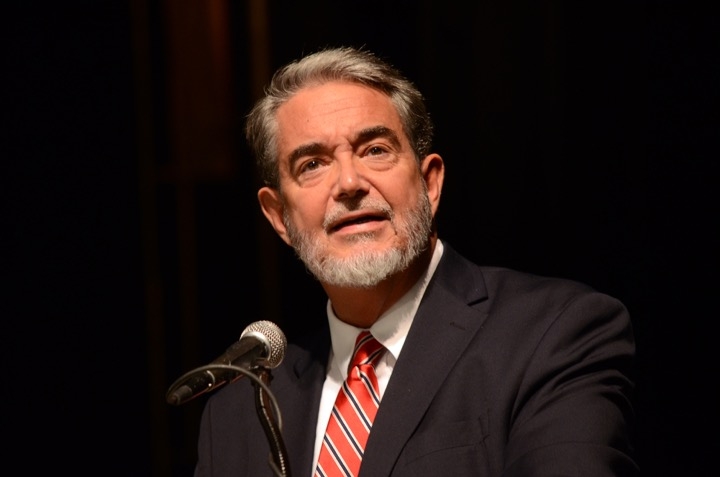

Scott Hahn is probably the most influential American Catholic author and speaker over the past three decades. An adult convert to the Catholic Church from Reformed Protestantism, Hahn serves as professor of theology and Scripture at Franciscan University in Steubenville, where he holds the Father Michael Scanlon Chair in Biblical Theology and the New Evangelization.

He is also the founder and president of the St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology. Among the many influences that were instrumental in drawing me back to the Catholic Church nearly 15 years ago was the book Hahn co-authored with his wife, Kimberly, “Rome Sweet Home: Our Journey to Catholicism” (Ignatius Press, $16.95).

I had grown up Catholic, left the Church as a teenager, and returned in late April 2007 while I was serving as president of the Evangelical Theological Society, a post from which I resigned a week after receiving the sacrament of reconciliation for the first time in more than 30 years.

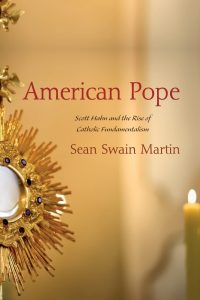

So when I first heard about the publication of the book, “American Pope: Scott Hahn and the Rise of Catholic Fundamentalism” (Pickwick Publications, $19), I was curious to see what the author, Sean Swain Martin, had to say about Hahn and his work.

An assistant professor of religious studies at Viterbo University in Wisconsin, Martin seems perfectly suited to produce such a book. Not only is it based on his University of Dayton Ph.D. dissertation, Martin has his own Catholic conversion story to tell, which he briefly presents in the book’s introduction. For these reasons, I expected to read a scholarly tome with rigorous and respectful analyses of Hahn’s publications in biblical studies and theology.

What I found was deeply disappointing.

With fewer than 110 pages of actual text, “American Pope” not only fails to provide the sort of serious inquiry that a figure of Hahn’s stature deserves, it is riddled with misleading descriptions, uncharitable interpretations, embarrassing inaccuracies, and logical non sequiturs.

Because documenting every one of these faux paus would exceed the space constraints of this review, and because others in several online venues have already responded to many of the book’s most egregious errors, I will focus exclusively on Martin’s central thesis that Hahn’s work and ministry represent something Martin calls Catholic fundamentalism, a view that seems to have more in common with American Protestant fundamentalism than authentic Catholicism. Because Martin does not define Catholic fundamentalism until the book’s final pages, one is not quite sure what he means by the term until one arrives at the end of the last chapter. But once one arrives there, one finds a definition that seems intentionally contrived to fit Hahn, even though, as we shall see, it still does not accomplish its purpose.

Martin tells us that despite Hahn’s conversion to Catholicism, he “fits all … the significant markers of Protestant fundamentalism” (110), which according to Martin are (1) “certainty born of common sense” philosophy, (2) belief in “a biblical inerrancy that matches fundamentalist understandings of inerrancy,” (3) the belief that “the Mass acts as a key that we can use to unlock the eschatological vision of the book of Revelation, revealing the realities of spiritual warfare and possibly depicting the end of the world itself,” and (4) the belief that “the Church Militant can have no peace with secularism and non-Catholic worldviews” (110). Let us now take a deeper look at each of these markers.

- Certainty and the Common Sense Tradition. Common Sense philosophy — in the American context — refers to a collection of views about knowledge, ethics, and scientific methodology associated with thinkers like Thomas Reid (1710-1796), Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), Francis Bacon (1561-1626), and Isaac Newton (1643-1727).

Historian Mark Noll notes in his 1985 American Quarterly essay on the subject (cited by Martin on Page 102) that the Common Sense tradition by the end of the 18th century had come to dominate American intellectual life. It rejected skepticism about the reliability of our senses to know the real world, while also suggesting that empirical science is the model by which each academic discipline — including biblical studies and theology — ought to categorize and analyze what it investigates. It was also a fallibilism philosophy, meaning that its advocates held that when our cognitive powers function properly, our knowledge of the world is reliable but not certain. For this reason, it is odd that Martin ascribes “certainty” to the Common Sense Tradition.

Conservative American Protestants appropriated this philosophy, and they were confident that by employing it in their study of Scripture and theology that they could show Christian faith to be rational by the intellectual standards of their day. But as the wider American intellectual culture in the 20th century began moving away from the Common Sense Tradition, conservative Protestants generally did not. For this reason, the style of Common Sense thinking continued to dominate the worlds of American Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism, especially in the way their leaders practiced apologetics.

It is very strange for Martin to attribute this thinking to Hahn. To be sure, Hahn’s own Christian journey begins in the conservative Protestant world, but what was instrumental in drawing him away from that world and into the arms of the Church is what he perceived as the inadequacy of conservative Protestant thinking on Scripture, tradition, the sacraments, and ecclesial authority.

Although Martin knows all this, he nevertheless saddles Hahn with the fundamentalist label because, according to Martin, Hahn in his writings reveals “a troubling certainty” (96), and certainty is a marker of fundamentalism. But Martin provides no actual evidence for his claim, aside from reproducing quotes from Hahn in which Hahn confidently affirms beliefs that Hahn thinks are true because they are tightly tethered to the Church’s traditions, practices, creeds, and reading of Scripture.

From these quotes and other citations, Martin infers Hahn’s troubling certainty. But it’s not clear how that makes one a fundamentalist or whether Hahn’s confidence in the truth of his beliefs even counts as certainty. After all, we all hold beliefs that we are confident are true. Martin, for example, himself seems quite certain that Hahn is a fundamentalist and that it’s bad to be one. But that hardly makes Martin a fundamentalist.

On the other hand, because, according to Martin, Hahn’s certainty is “born of common sense,” and we know that Common Sense philosophy is fallibilist, then it stands to reason that Hahn must be a fallibilist when it comes to certainty. (Hahn, from what I can gather from his writings, is a conventional Thomist when it comes to human knowledge, though as a biblical theologian that is not the focus of his scholarship).

Moreover, the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that on some matters we can indeed be certain. Take, for example, these passages: “These are also called proofs for the existence of God, not in the sense of proofs in the natural sciences, but rather in the sense of ‘converging and convincing arguments,’ which allow us to attain certainty about the truth” (31). “Faith is certain. It is more certain than all human knowledge because it is founded on the very word of God who cannot lie” (157). “Revelation gives us the certainty of faith that the whole of human history is marked by the original fault freely committed by our first parents” (390).

Another reason why it’s strange to place Hahn in the Common Sense tradition is that he has in his writings explicitly rejected the tradition’s nominalism, the belief that only particular things are real, that universals like “human nature” or “dogness” are merely words that human beings find useful when we categorize things. For example, in his voluminous 2013 book (co-authored with Benjamin Wiker), “Politicizing the Bible: The Roots of Historical Criticism and the Secularization of Scripture” (Crossroad Publishing, $59.95), Hahn makes a case against nominalism as well as against the concomitant mechanistic view of nature advanced by Bacon and Newton, arguing that such views are deleterious to the metaphysics that the Catholic sacramental worldview requires. But citation of this work is completely absent from “American Pope.” (By the way, Martin also ignores Hahn’s 2009 Yale University Press book, “Kinship By Covenant: A Canonical Approach to the Fulfillment of God’s Saving Promises” ($32), which has its origin in Hahn’s 750-page Marquette University Ph.D. dissertation [which Martin also fails to mention]). Such an oversight is tantamount to writing a book on St. Thomas Aquinas and ignoring the “Summa Contra Gentiles.”

- Biblical inerrancy. Martin’s case is even weaker when it comes to the other three “significant markers” of fundamentalism. As you recall, the second marker is belief in “a biblical inerrancy that matches fundamentalist understandings of inerrancy.” Although it is true that Protestant fundamentalists believe in biblical inerrancy, they virtually always conjoin it with a wooden, literalistic, and ahistorical hermeneutic that eschews the authority of Church and tradition.

Hahn clearly rejects that approach, while, of course, accepting the Church’s distinctly non-Protestant views on biblical inerrancy and interpretation. Martin, for some reason, is so determined to make Hahn a Protestant fundamentalist that when he tells us of Hahn’s reticence to rule out a futurist interpretation of the book of Revelation (in Hahn’s book (“The Lamb’s Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth” (The Crown Publishing Group, $13.99), Martin reminds us that such an interpretation “has long been a hallmark of traditional biblical literalism” (49).

Notice what Martin is doing here and compare it to how he assesses Hahn under the first marker. There Hahn is a fundamentalist because he exhibits “troubling certainty.” But here Hahn is a fundamentalist because he apparently exhibits troubling uncertainty since Hahn won’t rule out a futurist interpretation of Revelation.

- The Mass and the Book of Revelation. The third marker is referring to Hahn’s view that the Mass is the key to making sense of the eschatological meaning of Revelation. But because Protestant fundamentalism rejects the Mass altogether — not to mention the entirety of the Catholic sacramental worldview — this third marker seems custom fitted to net Hahn as a fundamentalist. Martin would have done just as well to have replaced this marker with “lives in Steubenville, Ohio” or “rhymes with ‘not Don.’ ”

- The Church at war with secularism. In the fourth marker, Martin is referring to Hahn’s assessment of the sustainability of the Church’s moral theology and social doctrines vis-a-vis the escalating secular hegemony of our cultural institutions.

In Hahn’s book, “The First Society: The Sacrament of Matrimony and the Restoration of the Social Order” (Emmaus Road, $22.95), he makes an extended argument for the good of marriage (and in particular, sacramental marriage) and the role it plays in advancing society’s common good. This implies, of course, that ideas, practices, and ways of life inimical to sacramental marriage — those, for example, that arose out of the sexual revolution and its aftermath — cannot be appropriated by the Church without doing damage to its moral theology and the souls whose good the Church is obligated to protect. And conversely, when it comes to the state, a government that officially severs its civil society from sacramental marriage (or at least something close to it) will undermine the good of its citizens.

Martin interprets all this to mean that Hahn is arguing that “the Church Militant can have no peace with secularism and non-Catholic worldviews,” which is, according to Martin, the fourth marker of Protestant fundamentalism. Setting aside the fact that Protestant fundamentalism is a non-Catholic worldview, Martin’s depiction is misleading.

Hahn is critical of secularism because its advocates often say that secularism is merely the belief that the state can and ought to remain neutral on deep questions of human nature and ultimate meaning even while they advance policies that privilege views and practices antithetical to the Catholic faith that they nevertheless claim do not violate the neutral principles of secularism.

Whether or not Hahn is entirely right about secularism is another matter altogether, one that I am sure many devout and informed Catholics will contest. But his position is a respectable one and has much in common with standard critiques of liberalism and secularism offered by thinkers across the political and religious spectrum.

The term “fundamentalism” was coined in the early 20th century to label a group of anti-modernist conservative Protestants whose theological views were associated with “The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth” (1910-1915), a multivolume collection of essays published to defend what its authors believed were the fundamentals of the Christian faith.

Although they defended doctrines with which Catholics agree, such as the virgin birth and the deity of Christ, they also defended doctrines with which Catholics disagree, such as justification by faith alone. Among the titles of the essays in the collection were “Is Romanism Christian?” and “Rome, the Antagonist of the Nation.”

Over time, the term “fundamentalism” came to be associated in the popular imagination with any unthinking, unsophisticated, and hidebound religious community whose members are content to remain invincibly ignorant of the serious intellectual and cultural challenges of the modern world. But as the term moved away from its descriptive historical roots and developed into a normative term of derision, it has essentially become a kind of conversation-stopping slur that functions to inhibit rather than advance dialogue between those inside and outside the Church who disagree with one another.

Thus, when Martin labels Hahn a fundamentalist, he is not only inaccurate as to its original meaning (as we have already seen), he is inhibiting his readers from acquiring an appreciative though critical understanding of Hahn’s views and beliefs.