Born with cerebral palsy, the poet Molly McCully Brown explores the paradoxical divide between a broken body and a soul made for God.

The Incarnation: central miracle of our faith. Veiled in flesh the Godhead see! Emmanuel! God is with us, among us, sporting a body like ours.

St. John Paul II taught that the human body is a sacrament, which St. Augustine describes as “an outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible grace.”

What was the inward and invisible grace of Christ’s body? That he is God and he is love, the likes of which we can’t imagine.

And the inward and invisible grace of our own bodies? That we are made, and made by this God of unimaginable love, and in his image and likeness. “The image and likeness of God” apparently means that body is welded to soul in us. To God, that seems to be the utmost love.

Truth to tell, though, this blessing is often a burden. We just don’t pull it off very well. We’re seldom what we were designed to be, what we could be, in body or soul. Our body, our spirit, or both often drag us into hurtfulness.

The body gives us the world — but locks us in our skin. The soul can never quite transcend the body. When body or soul falls into sin, the other has no choice but to follow. We want our soul to go to heaven, but surprise! We’ll meet our confounded body there, too, like it or not.

It’s dizzying. It’s too immense to wrap our brains around. Man in the image of God, God in the image of man. After all this time, we still don’t know what to do with that.

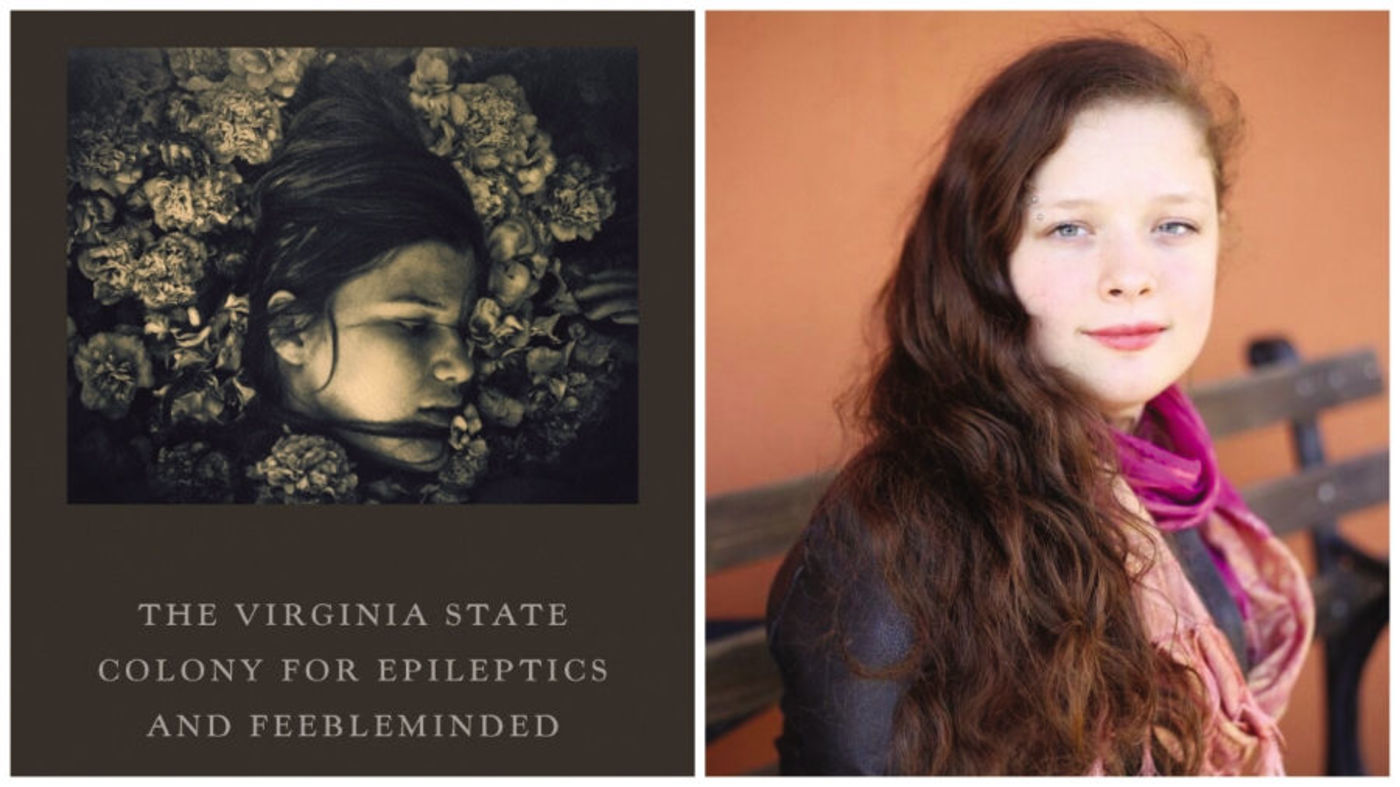

In “The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded” (Persea, 2017), Molly McCully Brown’s first book of poems, the shifting, misty divide between body and soul is the central character without ever being mentioned.

The Colony was a real place located near Brown’s girlhood home, and this was its real name. Dreamed up by devotees of the newly popular science of eugenics, the Colony opened in 1910, and in the 1920s began sterilizing patients who had epilepsy, mental retardation and other physical, mental, and intellectual disabilities. Between the 1920s and the mid-1950s, the Colony surgically sterilized more than 7,000 “defectives.”

Brown’s poems give clear voices to imagined Colony patients and staff during 1935 and 1936.

Here, life as a Colony patient:

An employee who rapes patients:

The resumption of daily life after surgical sterilization, which doctors neither explained nor sought permission to perform:

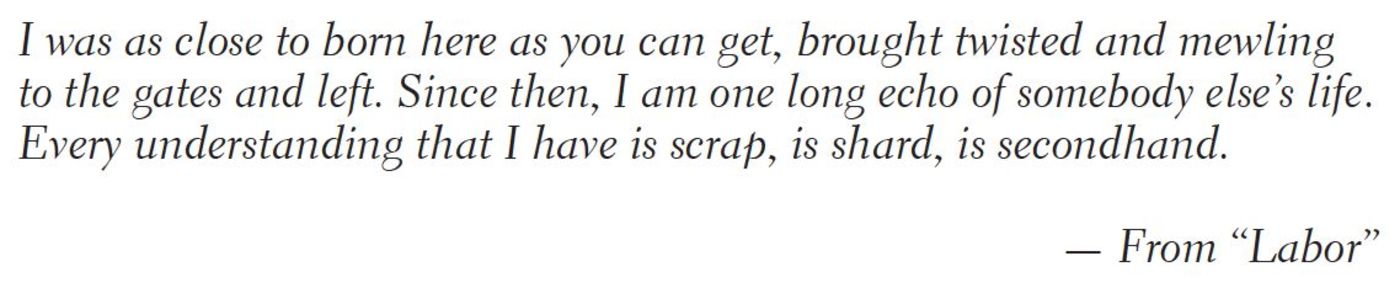

Brown knows a blessing when she sees one. She grew up near the Colony, and she has cerebral palsy.

Her great good fortune is that she was born to professional parents who cherished her — novelists John Gregory Brown and Carrie Brown — and born late in the 20th century. By then the Colony, and the many facilities like it in the U.S. and abroad, had repudiated eugenics and begun to offer real services to people with disabilities. (Now called the Central Virginia Training Center, the facility cares for about 400 people with intellectual disabilities in its intermediate, skilled nursing and acute care centers.)

These poems show Brown’s comprehension of the enormity of the curse she escaped while others did not.

Growing up with a serious physical disability meant years of surgery and medical scrutiny for Brown. A lifetime of pain, doctoring and therapy, she says, “gives you this weird notion of your body as an inherently damaged, inherently painful thing that has needed fixing from the moment you came into the world.”

Her case is extreme, but feeling “inherently damaged” and as if you have “needed fixing from the moment you came into the world” is the human condition.

“Some sense of alternating between being in harmony with and being in discord with who you are in your soul and in your body — that’s part of being a person walking around in a body in the world,” she says.

“I have had and do have resentment for my body. But I am simultaneously aware of how many of the things that I know and like about myself and my life are tied to my body and to who I am as a physical person. And I’m often grateful to be in the particular body that I am,” she adds.

These two opposing human realities are “in tension in an interesting way” for Brown. She has been fascinated by the overlapping of the embodied and spiritual worlds for as long as she can remember. “That’s my jam,” she says. “That’s where I exist.”

Humans, being both physical and spiritual, have language that shares those dual realities. “When we articulate, we take the physical and render it spiritual, and we take the spiritual and render it somehow material,” says Brown.

Poetry has always been about the quest to use the perfect concrete words in the perfect concrete way to perfectly articulate an abstract thought or emotion. Brown deftly handles the natural metrics of conversational speech. She fills those comforting rhythms with just the right words, used in just the right way, to convey her sense of the Colony as chilling and chillingly human.

“The true relationship between groundedness and transcendence is what makes a poem mysterious and good,” Brown says.

She must certainly have worked her language hard during the book’s creation to have sustained such a calm, contemplative, almost reassuring tone throughout the revelation of these outrages. In the same way that the most terrifying horror movies show much less than they suggest, these poems suggest atrocities so beautifully, so enjoyably, that we can read right past the horrors before noticing and pulling up short in disbelief.

These spare, lapidary poems are made, not found, which is the highest praise. Brown has imagined ghosts and has given them stunning things to say. No one who reads these poems will come away untouched by the holy, unfixable mess of bodies and souls, patients and employees, at the Colony.

Brown has been a practicing Catholic since Easter 2015, but attended Catholic services for years before that. What attracts her and keeps her coming back to Catholicism is her interest in theology. And what fosters her interest in theology is the death of her identical twin when they were 2 days old.

“I feel deeply connected to her and I miss her enormously and I don’t feel as if she’s gone. I feel her absence and some version of her presence still in a very profound way,” Brown says. “There’s nothing in the rational world that helps that make sense to me. There’s nothing in the scientific world that sufficiently explains it. There’s nothing in the daily world that gives me enough of a framework to understand how I can love and hate being an embodied person in such intense ways simultaneously.”

And, she might add, nothing to help her understand how she can so strongly sense the presence and pull of her dead infant twin.

“When I participate in the Mass, I feel a connection to a body that is larger than myself,” she says. “There is no finding a boundary. The more thinking about it I do, the more I participate in the Church, the more times I take Communion and think about transubstantiation, the less I believe in real divisions between the material nature of the world and the spiritual component. They are one another. They’re in relationship all the time to such an extent that they are inextricable. Because we are made creatures and this is a made world.”

In Brown’s book, all the paradoxes arising from bodies welded to souls are made manifest.

Patients with “inherently damaged” bodies and minds are held in captivity. Who are these patients? Their caretakers are held in a different kind of captivity, and may surreptitiously perform small kindnesses or just as surreptitiously create a living hell. Who are these caretakers?

Bodies and souls find beauty in the dustiest corners. Somehow, an Incarnation takes place: God, we come to suspect, is living at the Colony, in this human tangle of bodies and souls. He puts them on and lives their lives.

“For me, being a Catholic is part of what makes it possible for me to be at home with paradoxes — and those paradoxes can be both unsolvable and true,” says Brown. “Being Catholic helps me know how to live in a body that I simultaneously love and despise.”

Jane Greer edited and published “Plains Poetry Journal” and is author of “Bathsheba on the Third Day.”