There is no doubt that the people of Ukraine are living Advent very differently than Westerners this year.

Instead of shopping and parties, many citizens will face bombardments, electricity outages, and lack of heat as the Russian invasion, begun on Feb. 24 of this year, continues unabated. Nonetheless, Ukraine’s Christmas traditions, which have survived wars, starvation, and an atheist iron curtain, can offer much solace to its beleaguered people.

Indeed, there are even more opportunities for rejoicing since Christmas can now be celebrated on Dec. 25 as in the Gregorian calendar, as well as on the traditional date of Jan. 7, based on the Julian calendar. Whichever day they choose, it will be an opportunity to shine some much-needed light in this very dark winter.

Like most parts of the world, Ukrainians celebrate the coming of Christ by feasting. The table ritual, however, carries a greater meaning for a people who were brutally starved by the Holodomor, a Soviet-manufactured famine that killed somewhere between 4 to 8 million people between 1932-33.

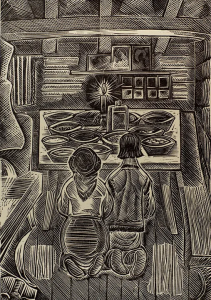

“At Christmas,” Georgy Yakutovych, 1965.

The breadbasket of Europe, Ukraine’s rich, dark, soil is celebrated during the “Sviata Vechera” (“Holy Supper”), traditionally held in the presence of the whole family. Twelve courses, each one symbolizing an apostle, are arranged at the holiday table; meatless however, as Christmas Eve is a day of abstinence.

Wheat figures prominently in the meal: hay strewn on the embroidered tablecloth recalls Christ’s manger, the first course, called “kutia,” is a grain, honey, and poppyseed staple, while the “didukh,” bound grain stalks symbolizing the family ancestors is positioned at the place of honor. Three loaves of braided bread, the uppermost decorated with a candle, crown the Christmas spread.

Some of the customs such as the “didukh” derive from a pagan past, but like the Christmas tree, have been absorbed into the Christian culture. Ukrainians leave an empty place at the “Sviata Vechera,” meant for the deceased members of the family. Sadly this year, there will be many lost loved ones remembered at the Christmas table.

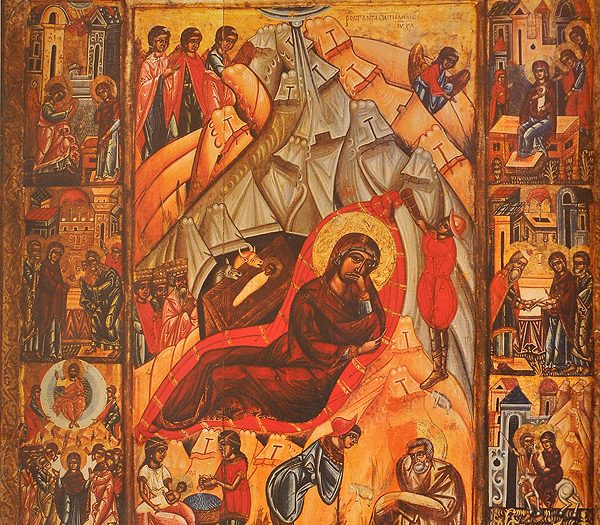

The Ukrainian love of art, manifested in frescoes, architecture, sculptures (like the tiny carvings at the Mykola Syadristy Microminiatures Museum in Kyiv,) and embroidery, is wonderfully expressed in their Christmas imagery. One of the oldest extant representations dates back to 1397, an illumination in the margins of the Kyiv “Psalter.” Divided into three sections, the parchment contains a rocky landscape with angels in the upper area, a middle section where the Virgin and Child are placed in a cave, and then a lower zone where more mundane activity takes place. This division underscores the Trinitarian nature of the scene, while the bright colors and numerous striations add a liveliness to the event.

The 16th century produced the stunning “Nativity of Christ” icon from the village of Trushevychi in the region of Lviv. While Western artists of the Renaissance vied to make their names known, icon writers in the East worked in humble anonymity. Nonetheless, this artist’s efforts proclaim the glory of the Incarnation with as much power as a Renaissance fresco.

The largest figure is that of Mary, “Theotokos” (“God Bearer”), occupying the center of the work. She is robed in a purplish mantle underscoring her queenly mien, but her robes define her body, an innovation from earlier versions, emphasizing her human body that carried the Lord. The red drape that surrounds her symbolizes the burning bush of Exodus 3, and is knotted at either end, an elegant allusion to the Virgin Birth.

Her hand to her lips, she reminds us of the mysteries she has seen, but treasures in her heart. The Christ Child tightly wrapped in swaddling clothes appears less like a baby than a shrouded body in a tomb, foretelling his eventual sacrifice.

Above and below, once again angels appear and humans work, but this icon continues to celebrate the Blessed Virgin throughout the frame. The scenes along the sides are all scriptural — the Annunciation, the Presentation, the circumcision — but the lower section shows apocryphal scenes that will grow into Marian feasts. The badly damaged lower left corner shows the birth of the Virgin, followed by scenes of her arrival at the Temple, her dormition (assumption) and her powers of intercession.

The 18th and 19th century saw caroling scenes dominate Christmas art, allowing Nativity scenes to languish, and during the 20th century when Ukraine was subsumed into Soviet territory, religious imagery became as unobtrusive as the Nativity itself. Postcards by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, who fought against Nazi Germany and the Soviet occupation, featured images such as the Bethlehem star above a concentration camp, or winter scenes in the national colors of blue and gold, or a snow-covered soldier, and raised awareness of the Ukrainian battle for liberty as the world welcomed the Prince of Peace.

In its few years of freedom, Ukraine saw a revival of Christmas icons in a new sumptuous yet austere style, such as Danylo Movchan’s “Christmas” from 2013, where the rich colors of the Virgin recall the Trushevychi icon but the stark blocks of color and the vigilant St. Joseph reveal a more modern vision.

“Sviata Vechera,” Ostap Lozynskyi, date unknown.

This Christmas there will be an empty seat around the “Sviata Vechera” for Ostap Lozynskyi, one of the brightest stars of new iconographical firmament, who died in 2022 at age 38. His nativities ranged in style from folksy to meditative, evoking homey cheer or solemn mystery.

His “Nativity” (contemporary) used an unconventional palette of slate, ocher, crimson, and teal, in a striking composition where the Christ Child is connected to his mother, yet mirrors the gestures of St Joseph. Friends and admirers noted that Lozynskyi loved Christmas, his favorite subject to paint, making his passing on Jan. 6 (Christmas Eve in the Julian, or Orthodox, calendar) all the more poignant.

A singular Ukrainian iconographic tradition is the “vertep,” a portable puppet theater, which presents the Nativity scene. Probably inspired in the 16th century by Western mystery plays, the “vertep” bears many similarities to the Neapolitan crèche. Like Italian Nativity depictions, there could be up to 40 characters, and the scenes gave ample space to daily life and activities.

Instead of being laid out in a cityscape or landscape, however, the Ukrainian “vertep” takes place inside a two-storied box, like a dollhouse. They were traditionally animated by hand puppets, operated by a single master. The upper level staged the sacred scene with angels, shepherds, oxen, asses, magi, and the Holy Family, while the lower level could feature Herod, Satan, death, Russian soldiers, gypsies, Poles, Jews, or assorted peasants. During the years of Soviet occupation, the lower scenes often made allusions to the political situation, giving the atheistic regime an excuse to discourage the practice to the point of extinction.

A traditional Ukrainian "vertep," or portable puppet theater. (Gruszecki/Wikimedia Commons)

Recent years have seen the revival of the “vertep,” particularly among the young artists of Lviv, historically one of Ukraine’s greatest cultural centers. One 2016 version featured live performers, setting the Nativity against the backdrop of the 2014 Russian aggression.

Soldiers, whose faith is flagging, fear the star in the sky, but are assured by angels of the good news. Light battles dark, good combats evil, the wise men are transformed into a volunteer, a doctor and a journalist, and the devil wields corruption and despair, taking contemporary suffering and blending it into salvation history.

While forces of darkness will loom over Ukraine’s wartime Christmas, the rich Nativity traditions of its people offer a light of hope to lead them through this joyous season.