Robert Duncan, the influential San Francisco poet, once lamented that the esteemed William Carlos Williams wouldn’t praise Duncan’s own poetry, but “went wild” and “wrote at great length” in lauding the work of Mary Fabilli.

Duncan’s envy came from a place of admiration; he’d published her work in his Berkeley Miscellany, along with Jack Spicer. In fact, Duncan said that he printed the magazine “at his own expense in order to get into print Mary Fabilli.” Critic Brenda Knight called Fabilli “a quiet voice amid the howls, raps, and roars of the Beat Generation.”

Her life and work deserve renewed attention.

Mary Fabilli is best known in the literary world from her marriage to William Everson. A poet and distinguished handset printer, Everson met in Fabilli in 1946, after he spent the war years in a foresting camp for conscientious objectors in Oregon. A cradle Catholic, Fabilli had wavered in practice but recently returned to her faith before meeting Everson. She’d play a phonograph record of Gregorian chants while he wrote in the house on Sundays. The “tremendous sublime” moved him; it gave his life a sense of “sacramental norms.” Fabilli’s faith was “profoundly physical. The concrete, sensible dimension pervading her whole mode of life.”

Before their relationship, Everson was a pantheist, but he’d tired of that impersonal spirituality. Fabilli gave him St. Augustine’s Confessions: “Not only did I perceive my soul there, but it let me see something of the true stature of this baffling belief that challenged my old incertitude: those elusive elements that are almost the last things to come to you, the mysticism and the mind.” Fabilli’s Catholic life was the witness needed to fully awaken Everson’s desire for God: “She told me the mysticism was there, in the mystery of the Mass.”

He was stirred by her devotion, and started attending Mass with her. After a few moments in prayer, he “soon sank sighing back on the pew,” but she remained kneeling. He wondered: “What revelation did she wait for, something which in its very expectation sealed me off in my plight?” Everson soon became enthralled with Catholic faith, and converted. Their marriage was annulled when Everson joined the Dominican Order as a lay brother in 1951, taking the name Brother Antoninus.

But Fabilli’s role in bringing Everson to the Catholic faith should not be the entirety of her literary memory; she was an accomplished and unique artist in her own right. Born in 1914 in New Mexico to Italian immigrants, she graduated from the University of California, Berkeley in 1941, with an art degree and a minor in English. Before she even graduated, her talent as an artist — a portrait done with sumi on rice paper — was being recognized in the art journal Parnassus.

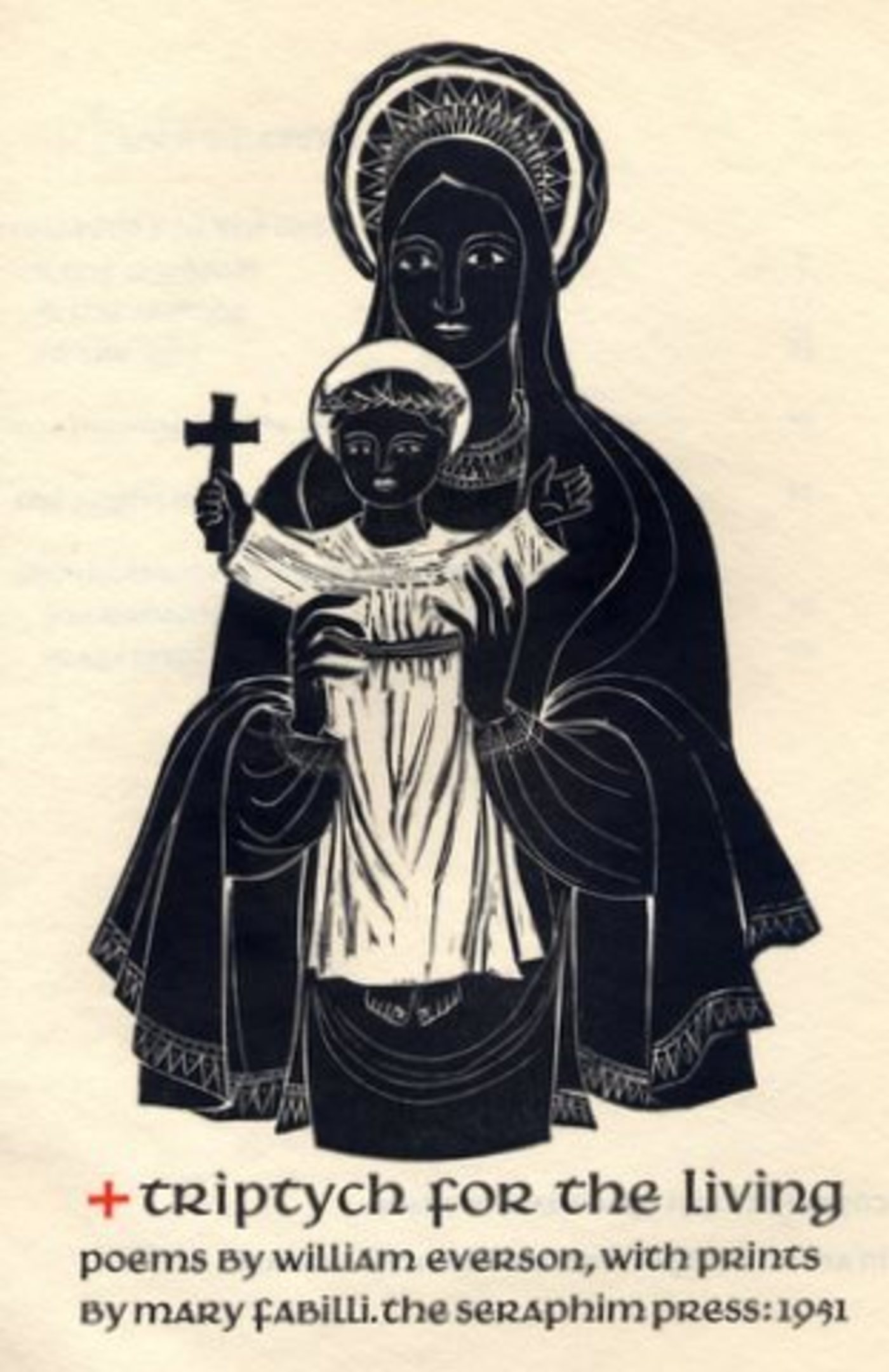

Fabilli illustrated Robert Duncan’s “Heavenly City, Earthly City” (1947), and created beautiful woodblocks for William Everson’s “A Privacy of Speech” (1949) and “Triptych for the Living: Poems” (1951), including a Madonna and child gracing the title page. For her limited-print collection “Saints: Nine Linoleum Blocks” (1960), Fabilli asked Everson, then a lay brother, to pose for two of the saints in the collection.

At the same time, Fabilli was writing and publishing poetry. “Some of my poetry is formal and straightforward and rational, not deranged like the other stuff (language poetry) out of a dream world,” she said, comparing her work to that of her more experimental contemporaries. “You may have to search, but you will always find my love for God in my work.” The final stanza of her poem “Advent” is gentle and optimistic: “Snow falling on Christmas trees / deep in the forests of Arizona, / and falling fast in Zion, / while the angels sing in a strange land, / peace and companionship— / the child that is born to us— / sing songs of him in all the mesas / after two thousand years.”

Other poems like “December Evening” show her dexterity with language and sound: “The Argentine tango / weaves through my rooms / a voluble python / civilized / non-venomous.” After her debut book “The Old Ones” (1966), Fabilli published “Aurora Bligh and Early Poems, 1935-1949” (1968). Aurora Bligh was also Fabilli’s occasional publishing pseudonym; she contributed a prose piece, “The History of the Secret Guardian,” under this name to the New Directions annual anthology.

“I love poetry,” Fabilli said, “but I had to make a living” — hence her longtime affiliation with the Oakland Museum. She served as associate curator there from 1966 to 1977. Fabilli continued to write, and her concerns became more and more spiritual as she advanced in age. At 90 years old, she wrote: “At the moment of my death (this is what I believe) Christ will judge me and I will accept His judgment. My soul will go to where it belongs — to Hell, Purgatory, or Heaven! I hope it goes to Purgatory for purification, a fierce experience like no fire on Earth, and then to Heaven, so I can see God face to face. But God is a spirit and cannot be seen with bodily eyes; the soul has leapt its body and its eyes. It too is a spirit. How will it see God face to face? I do not know, but I believe it will. He who created images and sight and seeing will certainly provide!”

A member of the lay Dominicans for over 50 years, Fabilli is a unique writer whose presence in southern California crossed ideological lines. She played an important role in the San Francisco literary community. Far from a literary footnote, she should be remembered as a talented artist and poet.

Nick Ripatrazone has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is a Contributing Editor for The Millions. He is writing a book on Catholic culture and literature in America for Fortress Press.

Start your day with Always Forward, our award-winning e-newsletter. Get this smart, handpicked selection of the day’s top news, analysis, and opinion, delivered to your inbox. Sign up absolutely free today!