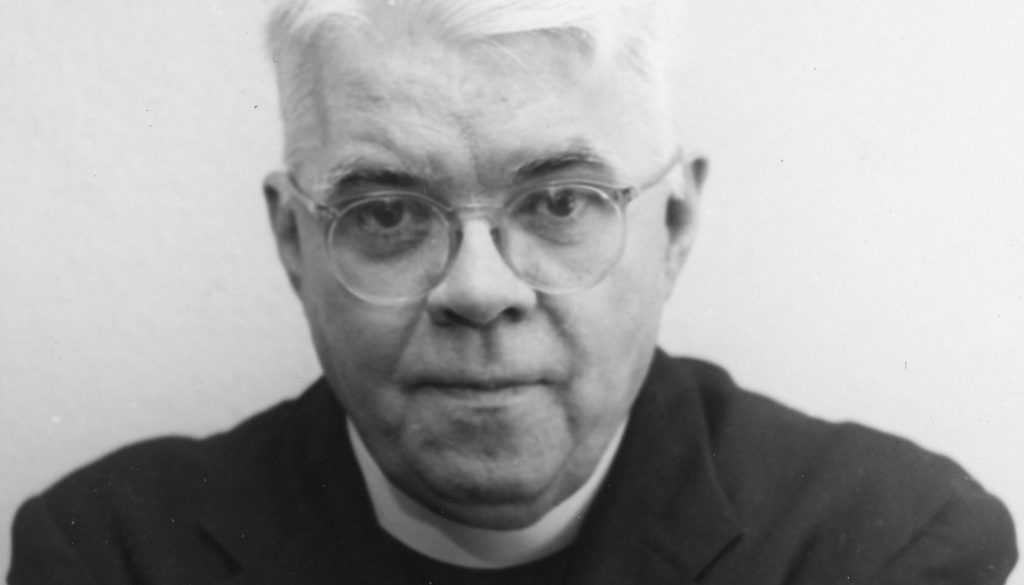

Reading Dawn Eden Goldstein’s well-researched new biography of Father Edward Dowling, SJ, whom Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) founder Bill Wilson described as his “spiritual sponsor,” I felt as if the priest had spent a week at my rectory. One detail in the book took me by surprise, nevertheless.

When Dowling died, his funeral was planned for St. Francis Xavier College Church at the Jesuit-run Saint Louis University, where he had studied and lived for a number of years. However, as Goldstein reveals, the pastor of the church did not want Dowling’s burial Mass held there. He suggested the small chapel of the Jesuit’s Sodality of Our Lady, where Dowling had been editor of its periodical, “The Queen’s Work.” Eventually, the Jesuit provincial intervened and the huge funeral was held at St. Francis Xavier.

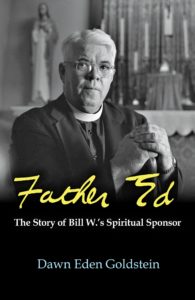

In “Father Ed: The Story of Bill W.’s Spiritual Sponsor” (Orbis, $26), Goldstein speculates that the reason for the pastor’s reluctance was because “in the hierarchy of Jesuit elites, Father Ed was the lowest of the low. He was not on the staff of America magazine, neither was he a university professor or a pastor. All he did was counsel people with problems — including drunks, drug addicts, and the mentally ill.”

This note about exclusion within the ranks of his own company helped me get a better handle on the life and career of “Father Ed,” as he was called by most.

He was involved in a ministry that could be called conservative, the sodality, and was close to Father Daniel Lord, SJ, who helped develop the morality code for Hollywood in the 1930s.

Yet Dowling had an irresistible attraction to the down-and-outers.

Goldstein thinks that the novitiate experience was hard for Dowling and that “touching bottom” there was the source of his compassion for those who are generally left out of the scheme of things or looked down on.

A Jesuit confrere once joked that the people who would come to Dowling for marriage preparation were all convicts, prostitutes, and drunks. But like Jesus, Dowling saw his ministry not to the righteous but to the sinners.

Dowling’s relationship with Bill Wilson has made this new biography of interest to those “in the program,” as people in Alcoholics Anonymous refer to membership in their organization.

Goldstein tells us that Father Ed learned about AA through his friendship with Ed Lahey, a journalist friend, and then searched out Wilson because he saw resemblances between AA’s “Twelve Steps” and the spirituality of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the Jesuit’s founder.

The priest had a knack for showing up when people needed a good listener. In one article, he is quoted as saying, “I really haven’t done anything. It’s really simple. I just happened to be around.”

Bill W., as he is known in AA lore, made his own “Fifth Step” with Dowling, describing this step as admitting to “God, oneself, and to another human being the nature of our wrongs.”

Goldstein shows what a complicated person Wilson was, describing his marital infidelities and his struggles with depression. He was in therapy for years with a Jungian psychologist and, although he toyed with the idea of converting to Catholicism (going so far as to take instruction with Ven. Bishop Fulton Sheen), he also had a fascination with seances, and experimented with LSD in an effort to expand his consciousness.

Presumably, Dowling helped steer him through some of those dangerous straits. Wilson called Dowling the most spiritual person he knew, adding, “I don’t know anyone who has contributed more of himself to his fellow mortals.”

But Dowling was not just a priest for alcoholics. He was involved in what we would now call “social justice” ministry. Passionate about politics, he advocated for something called “proportional representation” in voting, and was a firebrand on the lecture circuit.

He once said, “The two greatest obstacles to democracy in the United States are, first, the widespread delusion among the poor that we have a democracy, and second, the chronic terror among the rich, lest we get it.”

He knew Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin and was friendly with the Catholic Worker movement. Maybe it was his political radicalism, or perhaps his restlessness, but he was sympathetic to the radical economic program of Father Charles Coughlin, the famous radio priest who was accused of anti-Semitic and fascist tendencies. He also gave a hearing to the isolationist “America’s First” arguments of Charles Lindbergh, a strange attraction given Dowling’s leadership against racism and prejudice.

By temperament it seems, Dowling cast his lot with the outsiders and outriders of Church and society.

He expressed his doubts about “Churchianity,” which he contrasted with authentic Christianity. He could see the downsides of the Church as an institution, but joked that if you want running water, you have to be in favor of plumbing.

He was drawn to the creativity of movements of the laity. Dowling seemed to have never met a Church movement he couldn’t like, promoting “Cana Conferences” for married couples in addition to Twelve-Step programs for mental health and other problems.

He believed in what he called “isopathic groups,” associations of individuals with the same problem who helped one another in solidarity. This was exemplified by Alcoholics Anonymous, of course, but he extended this principle. He helped found Divorcees Anonymous for women who had been divorced, and another group he called “Seven Up,” for mothers with that many children or more.

Goldstein’s book is a portrait of a creative priest who also intersected with an important chunk of American Catholic history. Dowling comes across as a very modern priest for his time, although his way of life was traditional and his asceticism was classic in style.

Dowling said that he was grateful for his physical sufferings (caused in part by spondylitis deformans, a debilitating type of arthritis) because they helped him spiritually. His friends knew him to be a man of prayer who spent a lot of time before the Blessed Sacrament.

I am grateful for this biography, although at times Goldstein’s sympathy with her subject leads her to overreach, offering speculations about Dowling’s feelings and states of mind that can’t possibly be corroborated.

For instance, she speculates that when his brother died in the influenza pandemic, Dowling must have worried about whether he had carried the virus asymptomatically and caused his brother’s death.

Her imagination is her strength, but it can also be her weakness. Another example: She describes a woman waiting for Dowling at his office wearing a veil, because that was stylish in those days.

These are quibbles in comparison to what Goldstein has achieved in her research and writing.

Goldstein has brought Father Ed back from the dead to inspire us and make us think. Mavericks on the margins like him are a “creative minority” and a source of charismatic leadership in an institutionally oriented Church. A very worthwhile book.