I have been thinking about a remarkable scene from a prize-winning, contemporary French novel: a priest of a small parish in Normandy, France, has a good relationship with the Communist mayor of the working-class town.

At dinner, the mayor remarks that he and the priest have a similar problem in that people have left both the Church and the party. The political rallies of the Communists in France are poorly attended, and there is little identification with its ideals; the priest says Mass to an empty church.

Except, responds the priest, that even if there are only two people in the church, God still shows up.

“These empty hands can bless bread and wine, and it becomes the body and blood of Christ,” he says.

The author writes that this priest makes the Mass as solemn as possible, even when poorly attended. “Certain priests were builders, others preachers, others prophets. For him, what filled him and made him righteous was to fold his hands around a piece of bread and lift it up slowly and gravely, an instrument of the ineffable.”

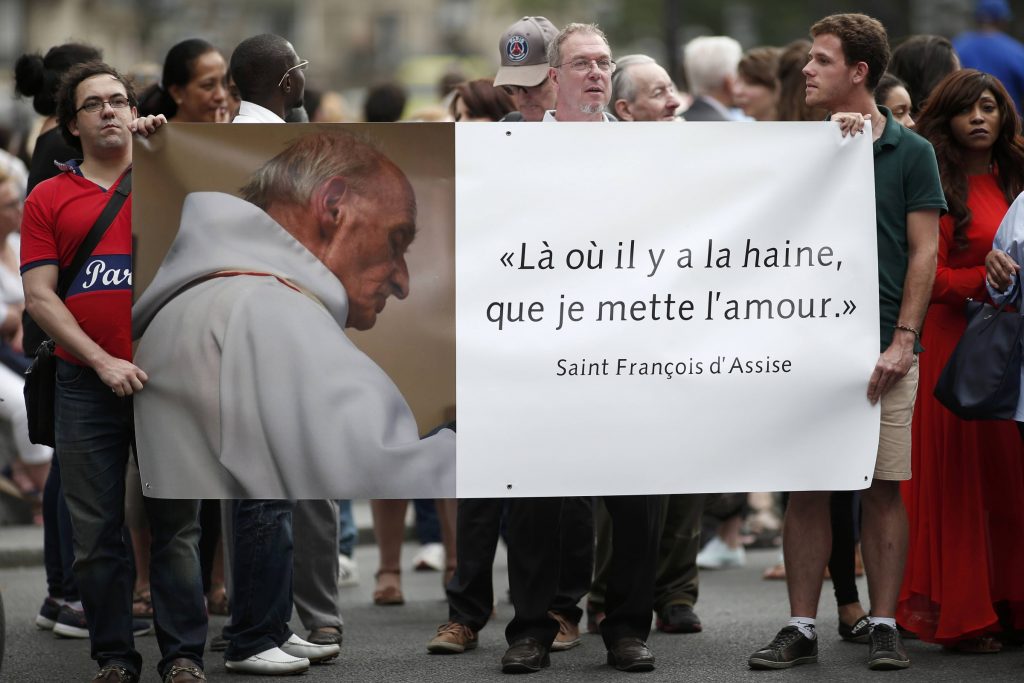

The novel is called La Grande Épreuve (“The Great Test”) by Etienne de Motety, a French writer and journalist (the book has yet to be translated into English). It is based on the true story of the assassination of Father Jacques Hamel on July 26, 2016. Isis-affiliated terrorists interrupted his daily Mass and cut his throat, purportedly because of France’s intervention in the Syrian conflict. The murder shook France and the entire world.

Montety says that he was inspired to write a novel based on the event because he was struck by “the eruption of violence in a place of peace, in a sacred place, of the extraordinary in an ordinary life on a summer morning in a provincial town.” Critics remarked that only by means of a novel could the story of the death of a priest at Mass be given a context in the cultural storm that is France today.

The fiction follows the lives of several people, including the priest, as they converge on the country parish where the murder takes place. The priest, Father George Tellier, was a late vocation who, like Father Hamel, had lived in Algeria before discerning the call to the priesthood. In the novel he had recently transferred parishes because of a distraction or temptation in his ministry. When the bishop asks him, “What is the problem at St. Martin’s?” he answers, “Me.”

The other characters include Sister Agnes, a religious of a congregation inspired by St. Charles de Foucauld, who has works in social service in a Muslim section of town. Hicham, the son of Moroccan immigrants, has been radicalized by Isis jihadists in prison. He converts David, the adopted son of a French couple, Francois and Laure, to a militant form of Islam from the superficial Catholicism in which he was raised.

Frederic Nguyen, the assimilated grandson of Vietnamese refugees, is the captain of the anti-terrorist police who arrive on the scene of the assassination too late. The profiles of the main characters paint a panorama of French society in the 21st century.

“Islam came to shake up a society in which Christianity has bit by bit ceased to rule over behavior and consciences,” says the author. In the novel, David is gradually immersed in deep net propaganda that leads him to the decision to kill a priest in church.

The contrast between militant Islam and watered-down cultural Catholicism makes Montety wonder if the Church is going to be replaced by Islam in the consciousness of France. Secularized France uses churches for events celebrating birth (baptisms) and death (funerals). At one point Father Tellier says that his church only fills up when there is a funeral (something which made me wince, because I could say the same about my parish).

Ironically, the ending of the novel is the most optimistic part of the book. The priest dies heroically, grateful that he has locked the tabernacle so that there is no danger of sacrilege. His death is foreshadowed in the novel in a scene in which the priest prays alone in the church. “He looked at the crucifix, and saw Him,” (with the capitalization in the French). In a sign of solidarity, Muslims who did not approve of the murder attended his funeral.

Pope Francis has called Father Hamel a “martyr” and sped up his canonization process. This novel made me think of Tertullian’s wisdom, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.” To that I say the familiar Hebrew word, “Amen,” meaning, “So be it.”